Module 4: Anxiety Disorders

Case studies: examining anxiety, learning objectives.

- Identify anxiety disorders in case studies

Case Study: Jameela

Jameela was a successful lawyer in her 40s who visited a psychiatrist, explaining that for almost a year she had been feeling anxious. She specifically mentioned having a hard time sleeping and concentrating and increased feelings of irritability, fatigue, and even physical symptoms like nausea and diarrhea. She was always worried about forgetting about one of her clients or getting diagnosed with cancer, and in recent months, her anxiety forced her to cut back hours at work. She has no other remarkable medical history or trauma.

For a patient like Jameela, a combination of CBT and medications is often suggested. At first, Jameela was prescribed the benzodiazepine diazepam, but she did not like the side effect of feeling dull. Next, she was prescribed the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine, but first in mild dosages as to monitor side effects. After two weeks, dosages increased from 75 mg/day to 225 mg/day for six months. Jameela’s symptoms resolved after three months, but she continued to take medication for three more months, then slowly reduced the medication amount. She showed no significant anxiety symptoms after one year. [1]

Case Study: Jane

Jane was a three-year-old girl, the youngest of three children of married parents. When Jane was born, she had a congenital heart defect that required multiple surgeries, and she continues to undergo regular follow-up procedures and tests. During her early life, Jane’s parents, especially her mother, was very worried that she would die and spent every minute with Jane. Jane’s mother was her primary caregiver as her father worked full time to support the family and the family needed flexibility to address medical issues for Jane. Jane survived the surgeries and lived a functional life where she was delayed, but met all her motor, communication, and cognitive developmental milestones.

Jane was very attached to her mother. Jane was able to attend daycare and sports classes, like gymnastics without her mother present, but Jane showed great distress if apart from her mother at home. If her mother left her sight (e.g., to use the bathroom), Jane would sob, cry, and try desperately to open the door. If her mother went out and left her with a family member, Jane would fuss, cry, and try to come along, and would continually ask to video-call her, so her mother would have to cut her outings short. Jane also was afraid of doctors’ visits, riding in the car seat, and of walking independently up and down a staircase at home. She would approach new children only with assistance from her mother, and she was too afraid to take part in her gymnastics performances.

Jane also had some mood symptoms possibly related to her medical issues. She would intermittently have days when she was much more clingy, had uncharacteristically low energy, would want to be held, and would say “ow, ow” if put down to stand. She also had difficulty staying asleep and would periodically wake up with respiratory difficulties. [2]

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Margaret Krone for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Treatment of anxiety disorders. Authored by : Borwin Bandelow, Sophie Michaelis, Dirk Wedekind. Provided by : Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. Located at : http://Treatment%20of%20anxiety%20disorders . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Bandelow, B., Michaelis, S., & Wedekind, D. (2017). Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 19(2), 93–107. ↵

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Henin A, Rapoport SJ, et alVery early family-based intervention for anxiety: two case studies with toddlersGeneral Psychiatry 2019;32:e100156. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2019-100156 ↵

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy in Patients with Anxiety Disorders: A Case Series

Mahendra p sharma, angelina mao, paulomi m sudhir.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Paulomi M. Sudhir, Department of Clinical Psychology, NIMHANS, Hosur Road, Bangalore 560029, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected]

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The present study is aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of a Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy (MBCBT) for reducing cognitive and somatic anxiety and modifying dysfunctional cognitions in patients with anxiety disorders. A single case design with pre- and post-assessment was adopted. Four patients meeting the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited for the study. Three patients received a primary diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), while the fourth patient was diagnosed with Panic Disorder. Patients were assessed on the Cognitive and Somatic Anxiety Questionnaire (CSAQ), Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ), Hamilton's Anxiety Inventory (HAM-A), and Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale. The therapeutic program consisted of education regarding nature of anxiety, training in different versions of mindfulness meditation, cognitive restructuring, and strategies to handle worry, such as, worry postponement, worry exposure, and problem solving. A total of 23 sessions over four to six weeks were conducted for each patient. The findings of the study are discussed in light of the available research, and implications and limitations are highlighted along with suggestions for future research.

Keywords: Anxiety , cognitive behavior therapy , dysfunctional cognitions , mindfulness

INTRODUCTION

In recent years there has been increasing interest in the application of meditation approaches in the management of mental health concerns.[ 1 ] Meditation is considered to be one of the three self-regulatory strategies that are effective in the management of anxiety.[ 2 , 3 ]

Mindfulness-based interventions can be traced back to one of India's most ancient meditative techniques, Vipassana meditation. The word Vipassana in Pali language means to see or observe in a special way and comes from two words, Vi , which means ‘special’, and passana, which means, ‘to see, to observe’. The word mindfulness is the English translation of the Pali word Sati and refers to being conscious, aware, observing, or paying attention.[ 4 ] It is a state in which one is required to remain psychologically present and ‘with’ whatever happens in and around one, without reacting in any way.[ 5 ] Thus, the practice of mindfulness meditation enables the person to respond consciously and reflectively, rather than react automatically to internal or external events. Kabat-Zinn (1982) developed the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, which is a clinical program to facilitate adaptation to medical illness.[ 6 ] MBSR consists of eight to ten weekly sessions,[ 7 ] and follows a skill-based, educational format.[ 8 ] Research indicates that a majority of people who have undergone mindfulness-based treatment programs have shown significant reductions in both physical and psychological symptoms.[ 9 – 12 ] Mindfulness-based interventions have been reported to be efficacious in a variety of stress-related medical conditions, and medical conditions with emotional disorders.[ 2 , 13 – 16 ] There is evidence for the usefulness of mindfulness-based interventions in India, across clinical and non-clinical samples, including tension headaches, obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, occupational stress, and coronary heart disease.[ 17 – 23 ]

It has also been effectively used in the management of anxiety and depression.[ 2 , 12 , 24 , 25 ] Segal, Williams, Teasdale (2002) developed the Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) for patients who had recovered from depression.[ 26 ] Their therapy is based on the effectiveness of MBSR in psychological and physical problems and it is an integration of the aspects of Beck's cognitive therapy for depression[ 27 ] with components of Kabat-Zinn's MBSR program.[ 6 ] The application of the MBSR program to anxiety disorder was first reported by Kabat-Zinn.[ 2 ]

Anxiety is unwarranted fear, excessive fear that interferes with the individual's overall functioning.[ 28 ] The six subtypes of anxiety disorders share common features of emotional experience and cognitive and informational processes. They are characterized by dysregulation of emotional, behavioral, physiological, and cognitive processes.[ 29 ] Researchers have examined the conceptual links between certain subtypes of anxiety, such as, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and the construct of mindfulness.[ 30 ] GAD is characterized by a chronic focus on future negative events along with a sense of apprehension. Worry, which is a hallmark of GAD leads to an experiential avoidance of anxiety, and thereby, prevents emotional processing that is required to overcome anxiety. Individuals with GAD habitually respond to non-existent perceived threats, rather than focusing on the present moment experience, which provides an alternative response that may facilitate adaptive responding.[ 31 , 32 ] Thus, the mechanism by which mindfulness works in anxiety is through a process of detachment between external contingencies and internal experience that is otherwise enhanced by worry and other types of verbal activity, as well as effective emotional regulation skills.[ 33 , 34 ] Habitual patterns of responding to cues and contingencies are gradually replaced by greater awareness of the present-moment experience and reflective focus. Monitoring techniques commonly adopted across cognitive-behavioral interventions can also be considered as a type of mindfulness exercises, which enhances awareness in patients.[ 29 ]

Mindfulness is also specifically associated with relaxation techniques — a common and essential element across a number of treatments for anxiety disorders and GAD, and Panic Disorder in particular.[ 35 ] Mindfulness-based techniques are likely to be most effective in reducing the cognitive component of anxiety, one of which is the worrisome thinking seen in GAD.[ 36 , 37 ]

The effectiveness of MBSR in the treatment of anxiety disorders has been well-documented and treatment gains are maintained at follow-up.[ 2 , 12 ] Cognitive methods help in the management of worries and in changing expectations and beliefs about vulnerability to dangers that are typical in all anxiety disorders.[ 38 ] Results from recent meta-analytic reviews indicate the effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies across populations presenting with anxiety and depression. However, this review also notes that studies have been carried out on heterogeneous populations that include medical illnesses, non-clinical samples, and only a few studies include psychiatric samples.[ 39 ]

A review of studies on MBCT has shown mixed results. Even as some support its effectiveness,[ 39 ] others are less confident of its benefits.[ 40 , 41 ] Thus, research studies in the field of mindfulness-based therapies indicate its efficacy in the management of anxiety. Some of these studies have also demonstrated the maintenance of gains over time.[ 12 ] Despite the increase in research on MBCT in emotional disorders, there has been little systematic effort to examine its effect on the Indian population. Anxiety disorders are also known to be debilitating and run a chronic course, hence, it is important to identify interventions that help not only symptom reduction, but also equip the individual with strategies to deals with exacerbations. MBCT can be a time- and cost-effective strategy in a setting like India, where a large number of people seek treatment for anxiety disorders. It would be important to understand its effectiveness in patients with anxiety disorders, as few studies have focused on specific diagnostic groups other than the depression and medical population. Hence, the present study is an attempt to examine the effectiveness of MBCT in reducing symptoms of anxiety and worry, and modifying dysfunctional beliefs in patients with anxiety disorders.

Methodology

A pre–post intervention design was adopted. Five clients (four males and one female) with a diagnosis of anxiety disorder were recruited from the outpatient mental health services of NIMHANS. However, one patient dropped out of the study and the final sample comprised of four clients (three males and one female) with a diagnosis of GAD and Panic disorder (F 41.1, F 41.).[ 42 ] Those with concurrent diagnosis of psychosis, organic brain syndrome, mental retardation, major medical illness, or previous exposure to cognitive behavioral intervention were excluded from the study. They were explained the nature of the study and their informed consent to participate was obtained before the start of the study.

A Sociodemographic and Clinical Data Sheet was used to obtain information on the demographic and clinical history. The behavioral analysis proforma[ 43 ] was used to assess specific behaviors in various areas including antecedents, historical, social, cognitive, and biological factors. The behavioral analysis provided the comprehensive data required for selecting the appropriate intervention strategies. Cognitive and somatic aspects of anxiety were assessed using the Cognitive Somatic Anxiety Questionnaire (CSAQ).[ 44 ] The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS)[ 45 ] was used as the clinician's assessment of anxiety. The frequency and intensity of worry was assessed by the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ),[ 46 ] and dysfunctional cognitions were assessed on the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS).[ 47 ]

Therapeutic program

The therapeutic program consisted of approximately 23 sessions for each client over a period of four to six weeks. The sessions were conducted individually. The specific components of the program were based on the MBCT program. It included self-monitoring of anxiety symptoms, education regarding the nature of anxiety and the different components of anxiety, relaxation training through mindfulness-meditation, and cognitive restructuring for modifying dysfunctional beliefs. The patients were trained in sitting mindfulness meditation. In addition, specific strategies for handling negative automatic thoughts and worries, such as, worry postponement and distraction, and cognitive strategies such as verbal challenging and reattribution were carried out. Each session lasted for approximately 60 minutes. Five sessions were spent for assessment at both time periods, and eighteen sessions for therapy.

CASE REPORTS

Mr. S, was a 34-year-old married male, a postgraduate, and was employed at the time of recruitment to the study. His chief complaints were those of continuous brooding and worries over matters related to the past and career, feeling inferior, anxious, and nervous, and he had palpitations since the last eight years, with an increase since two years. He was apparently doing well eight years back. He moved to Bangalore city after completing his graduation, to pursue a higher degree and was working to support his education. He found himself committing minor mistakes at work, for which his employer chided him. This made him feel inadequate and inferior to his colleagues and he would constantly compare himself to his friends. He was reluctant to approach his employer to ask for help and was apprehensive that his mistakes would be pointed in the presence of clients. Meanwhile, the client failed in his examination, which led to a sad mood and increased inferiority. He gradually began avoiding his friends. In addition, he felt very insecure about his job and began to worry about his career and future. He then resigned and subsequently changed jobs twice. Mr. S considered his life to be a complete waste, and felt like a failure and blamed himself for being a burden. He frequently experienced physical problems such as abdominal pain and digestive problems.

He reported a mild depressive episode 12 years back, with spontaneous remission. It was precipitated by a fight with his father. He shares a warm, close relationship with his wife. The patient is the first of the two siblings, born of a non-consanguineous union, and his father was very authoritative and strict. He reports that he never received emotional or financial support from his father in whatever he wanted to do in life, and therefore, had to be self-reliant. Mr. S was referred for the management of his anxiety symptoms.

Ms. B, a 37-year-old married woman, a computer engineer, but currently a homemaker, presented with complaints of intermittent tachycardia, breathlessness, choking sensation, palpitations, and thoughts that she would have a heart attack and collapse, with symptoms lasting for approximately ten to fifteen minutes. She had been experiencing these symptoms since the age of ten. She was apparently doing well till the age of ten, at which point she had an accident involving a truck when riding back home on her bicycle. Following this there was an incident of losing her grandmother due to cancer. Ten days following her grandmother's death she experienced a sudden onset of palpitations with breathlessness, accompanied by thoughts that she would die. The symptoms lasted for approximately 20 minutes, after which she felt better. These episodes continued for six months thereafter and in between the attacks she would anticipate the occurrence of another attack with dread. She became preoccupied with her health. Again at the age of 23, she experienced the same symptoms, which continued till the age of 27. During this time, she was also found to have developed sinus tachycardia. Her heart beat increased during her first pregnancy. It normalized after she delivered her child. During her second pregnancy, she once again had high blood pressure and had to be started on medication. In February 2003, she had one episode of sudden onset of palpitations and breathlessness, accompanied by tremors, an upset stomach, and fear that she was having a heart attack. An electrocardiogram revealed a normal report. Her palpitations subsided and the choking sensation, which she felt in her throat, resolved. A diagnosis of panic disorder was made. Since then, she has been constantly having tachycardia, and she is preoccupied with this.

The patient is the older of two siblings, born of a non-consanguineous union. There is a history of cardiac arrest in her paternal uncles. The patient's father has a cardiac problem. The client has been preoccupied with her health and illness since childhood. Her husband is concerned about her health, because of the episodes of panic. Premorbidly, she was well adjusted and sociable. A diagnosis of panic disorder was made and the patient was taken up for the study after consent was obtained.

Mr. RA, a 24-year-old unmarried male, pursuing his Master's degree, presented with complaints of headache, feeling tensed and anxious, and worried about his future, examinations, and family, which were pervasive in nature. He was apparently doing well till 1999. He was doing his under graduation at that time, when he became tense about his examinations. He wanted to do well, due to which he experienced headaches with vomiting. He was advised to take tranquilizers by his family doctor for 10-15 days. Thereafter, he became better and completed his internship. After this, his headaches worsened and would last the whole day. He would be extremely distressed due to the headaches. He frequently worried about his future, what he would do for his career. He would worry about any misfortune befalling his family whenever he read about disasters in the newspapers. Mr. RA felt he should always be the best in whatever he did. He was very stressed for the same reason at his work. He worked for two years and later joined his Master's course. He felt more tensed, as he believed that other classmates were better off than him in studies. He set high standards for himself regarding his work performance, especially with regard to the progress of his patients. He preferred not to spend any leisure time and pressurized himself to spend as much time studying. He would rush through all activities and would be hasty about his work. He felt tensed and anxious most of time and had significant physiological arousal. His past history was not significant. Personal history revealed that the client was prone to worry with regard to his studies. He was concerned with securing good grades and had excelled in academics. Premorbidly, the patient was reportedly anxious by nature and tended to hurry through any work, to ensure that he completed it on time. Mr. RA was referred for the management of his perfectionistic thinking and anxiety.

Mr. D was a 23-year-old unmarried male, a graduate from an urban background, and employed. He presented with complaints of being tensed and anxious, getting ‘butterflies in his stomach’, worrying excessively, and having difficulty in communicating with others. He described himself as having always been shy. He began interacting with others only when he was in college. He had recently started working, after completing his graduation. He was placed in the marketing as well as accounts section, and was required to talk to and interact with his customers during which time he would experience anxiety. He would also begin to stammer or would feel his mind go blank. During his weekly presentations, he would feel anxious. Often he felt tongue-tied and stated that he was unable to speak. His fear was marked when he faced authority figures and generalized to friends or family members. He felt he was unable to explain himself clearly due to his anxiety. The patient also had several concerns over domestic issues, especially related his to eldest brother. The patient would be angered over his brother's behavior, but felt helpless, as his efforts at changing the behavior of his brother had been unsuccessful. He was referred with a diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Phobia, for further management.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out on the four patients. Clinically significant changes (50% and above) based on pre- and post-therapy data[ 48 ] were used to assess the efficacy of the therapeutic intervention.

Pre Score – Post Score × 100 = Therapeutic Change

Using this formula the percentage of change between pre- and post-therapy points was calculated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

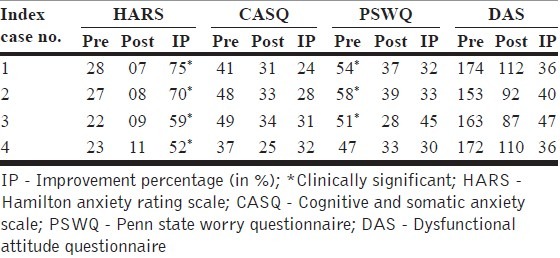

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) in the management of anxiety disorder. The first objective of the study was to study the efficacy of MBCT in reducing the anxiety symptoms of patients with anxiety disorders. The pre and post intervention scores of clients who completed therapy are shown in Table 1 . The analysis of the results for individual cases suggests that on HARS, an objective measure of anxiety, significant improvement was observed at the completion of intervention in all the clients. Analysis of group data for this measure also revealed that MBCBT was effective in bringing about statistically significant reduction in anxiety symptoms on the completion of therapy. The cognitive–somatic symptoms of anxiety as measured on the CSAQ reduced significantly at post therapy assessment. The improvement between pre- and post-assessment was found to be clinically significant. These findings on HARS and CSAQ suggest that MBCT was effective in reducing both physiological / somatic symptoms, as well as cognitive symptoms of anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders. These findings are consistent with the previous research, wherein, mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorder resulted in clinically and statistically significant improvement.[ 2 , 12 ] Although relaxation is not the primary aim of mindfulness meditation, it does produce the benefits of relaxation through its focus on breathing. This is also supported by various studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of MBCT on anxiety symptoms.[ 39 ]

Pre- and post-intervention assessment scores with improvement percentage for four clients who completed the therapy

The second and third objectives of the study were to examine the effectiveness of MBCT in the reduction of cognitive symptoms of anxiety, namely, worry and dysfunctional attitudes that contribute to and maintain anxiety. The individual case analyses suggest that there was consistent reduction in worry (PSWQ) and dysfunctional cognitions (DAS) with the progress of therapy, however, the improvement did not qualify for the criterion of significant clinical improvement (>50%). Post assessment, reduction in worry and dysfunctional cognition was clinically significant in comparison to the pre-assessment scores, for both the measures. Mindfulness is associated with developing an awareness of alternative perspectives and detaching from one's own habitual way of responding.[ 29 ] As such, it may have been an important element in altering the habitual patterns of worrisome responding. Mindful focus on the present moment experience provided an alternative response that may have facilitated adaptive responding.[ 36 , 37 ]

The modification of dysfunctional beliefs requires substantial time and this change takes place slowly.[ 2 , 12 ] The cognitive component of the treatment program results in significant change in dysfunctional cognitions. However, this change is not statistically significant and ranges from 36 – 47%. Alternative ways of coping with anxiety rather than merely reducing the maladaptive coping strategies are more likely to be effective in bringing about change.[ 49 ] In addition, anxiety disorder is characterized by an attentive bias to threat and a tendency to overestimate risk;[ 50 ] therefore, repeated focus on desirable outcomes may lead to a shift in the biased information processing, by making positive outcomes more evident and accessible. Borkovec (1999) hypothesized that a focus on desired action and choice is likely to decrease deficits in problem-solving and decision-making and increase the positive control of behaviors.[ 51 ] It is likely that if the therapeutic program had been longer, the changes in dysfunctional cognitions would have been more evident.

Mindfulness approaches that have been incorporated in several cognitive behavioral treatments for preventing relapse in depression[ 26 ] and substance abuse[ 52 ] and as part of a comprehensive treatment for borderline personality disorder,[ 33 ] have shown positive findings.

In conclusion, the findings of this case series indicate that MBCT can be an effective intervention in the management of anxiety disorders. The study has some significant implications. This is the first study to be carried out in India, which has adopted Mindfulness Meditation and Cognitive Therapy in the management of patients with anxiety disorder. Training in mindfulness meditation is cost-effective in terms of time and is applicable to a wide range of patients. All the clients who participated in the study were drug naïve. The significant reduction in anxiety symptoms that occurred in the patients following the intervention indicates that MBCT is an effective treatment method in the management of patients with anxiety disorder.

The small sample size is a significant limitation of the present study, as it does not allow for rigorous analysis of data and generalization of results. The inclusion of a control group would have strengthened the study. The absence of follow-up is another limitation, as it would provide information on the maintenance of treatment gains. Furthermore, the sample was heterogeneous with respect to diagnosis and a more homogenous sample would have been informative with regard to treatment.

Future research should be conducted with larger samples and follow-up to establish the efficacy of this program. The addition of a control group and a more homogenous sample would be helpful. The assessment of functioning and quality of life would further help in understanding the impact of the program on psychosocial outcomes.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

- 1. Walley M. The attainment of mental health - Contributions from Buddhist Psychology. In: Trent D, Reed C, editors. Promotion of Mental Health. Vol. 5. Aldershot: Ashgate; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical psychology: Science and practice. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2004;11:230–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG, Fletcher KE, Pbert L, et al. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–43. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Sharma MP. Vipassna meditation: The art and science of mindfulness. In: Balodhi JP, editor. Application of oriental philosophical thoughts in mental health. Bangalore: NIMHANS; 2002. pp. 69–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Nairn R. What is meditation? Buddhism for everyone. London: Shambhala Press; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain clients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical consideration and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Santorelli SF. Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical Center; 1999. Mindfulness-based stress reduction. Qualifications and recommended guidelines for providers. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Bishop SR. What do we really know about mindfulness based stress reduction? Psychosom Med. 2002;64:71–83. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Astin JA. Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation. Effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control and spiritual experiences. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:97–106. doi: 10.1159/000289116. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Kabat-Zinn J, Wheeler E, Light T, Skillings A, Scharf MJ, Cropley TG, et al. Influence of a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in clients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy [UVB] and photochemotherapy [PUVA] Psychosom Med. 1998;60:625–32. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00020. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Kristeller JL, Hallett B. Effects of a meditation-based intervention in the treatment of binge eating. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:357–63. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400305. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Miller JJ, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J. Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:192–200. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00025-m. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1350–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1350. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Baer RA, Fischer S, Buss DB. Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of eating disorder. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2006 DOI: 10.1007/s10942-005-0015-9. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ornbøl E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy - a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:102–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Sharma MP, Kumaraiah V, Mishra H, Balodhi JH. Therapeutic effects of Vipassana meditation in tension headache. J Pers Clin Stud. 1990;6:201–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Goyal A. Mindfulness based cognitive behavior therapy in obsessive compulsive disorder Mphil thesis. In: Shah A, Rao K, editors. Psychological Research in Mental Health & Neurosciences, 1957-2007. Bangalore: NIMHANS [Deemed University]; 2004. p. 371. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Narayan R. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in depression. MPhil thesis. In: Shah A, Rao K, editors. Psychological Research in Mental Health & Neurosciences, 1957-2007. Bangalore: NIMHANS [Deemed University]; 2004. p. 371. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Majgi P, Sharma MP, Sudhir P. Mindfulness based stress reduction program for paramilitary personnel. In: Kumar U, editor. Recent Developments in Psychology. New Delhi: Defence Institute of Psychological Research; 2006. pp. 115–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Parswani M. Bangalore: [Deemed University]; 2007. Mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR] program in coronary heart disease. Ph. D Thesis submitted to National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Majgi P. Bangalore: [Deemed University]; 2009. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention in reducing stress in paramilitary force personnel. Ph. D Thesis submitted to National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Kaur M. Bangalore: [Deemed University]; 2010. Efficacy of mindfulness integrated cognitive behavioral intervention [MBCBI] in Work Place Stress. M. Phil dissertation submitted to National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Kabat-Zinn J, Chapman A, Salemon P. The relationship of cognitive and somatic components of anxiety to patient preference for alternative relaxation techniques. Mind/ Body Medicine. 1997;2:101–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Mason O, Hargreaves I. A qualitative study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74:197–212. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for depression-A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Beck AT, Emery AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guildford Press; 1979. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [DSM-IV, 4th ed., text revision] Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Greeson J, Brantley J. Mindfulness and anxiety disorders: Developing a wise relationship with the inner experience of fear. In: Didonna F, editor. Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness. NY: Springer; 2009. pp. 171–88. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Barlow DH, Rapee RM, Brown TA. Behavioral treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 1992;23:551–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Expanding a conceptualization of and treatment for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Integrating Mindfulness/Acceptance-Based Approaches with existing cognitive behavioral models. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2002;9:54–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Borkovec TD, Hazlett-Stevens H, Diaz ML. The role of positive beliefs about worry in generalized anxiety disorder and treatment. Clin Psychol Psychother. 1999;6:126–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Menin D. Emotion regulation therapy: An integrative approach to treatment resistant anxiety disorders. J Contem Psychother. 2006;36:95–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Borkovec TD, Ruscio AM. Psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:37–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Borkovec TD, Inz J. The nature of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: a predominance of thought activity. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:153–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90027-g. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Lehrer PM, Woolfolk RL. Specific effects of stress management techniques. In: Lehrer PM, Woolfolk RL, editors. Principles and Practice of Stress Management. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 481–520. [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Wells A, Butler G. Generalized anxiety disorder. In: Clark DM, Fairburn C, editors. The Science and Practice of Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:169–83. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review clinical psychology. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:125–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Toneatto T, Nguyen L. Does mindfulness meditation improve anxiety and mood symptoms? A review of the controlled research. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:260–6. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200409. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders- clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Kanfer FH, Saslow G. Behavioral diagnosis. In: Franks CM, editor. Behavior Therapy: Appraisal and Status. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1965. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Schwartz GE, Davidson RJ, Goleman DJ. Patterning of cognitive and somaticprocesses in the self-regulation of anxiety: effects of meditation versus exercise. Psychosom Med. 1978;40:321–8. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197806000-00004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–95. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Weismann AN. The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A validation study. Diss Abstr Int. 1979;40:1389B–1390B. (University Microfilms No. 79-19, 533. [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Blanchard EB, Schwartz SP. Clinically significant changes in behavioral medicine. Behav Assess. 1988;10:171–88. [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Nemeroff CJ, Karoly P. Operant methods. In: Kanfer FH, Goldstein AH, editors. Helping People Change. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1990. pp. 122–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Clark DM. Anxiety disorders: why they persist and how to treat them. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37(Suppl 1):S5–27. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00048-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Borkovec TD, Roemer L. Generalized anxiety disorder. In: Ammerman RT, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of prescriptive treatment for adults. New York: Plenum; pp. 261–281. [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Marlatt GA. Addiction, mindfulness and acceptance. In: Hayes SC, Jacobson NS, Follette VM, Dougher MJ, editors. Acceptance and Change: Content and Context in Psychotherapy. Renovo, NV: Context Press; 1994. pp. 175–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (441.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Social Anxiety Disorder: A Comprehensive Case Study Analysis

Hearts racing and minds reeling, millions navigate a world where everyday interactions feel like walking through a minefield of judgment and scrutiny. This pervasive experience is the hallmark of social anxiety disorder, a condition that affects countless individuals worldwide, impacting their daily lives and overall well-being. To truly understand the complexities of this disorder and develop effective treatment strategies, researchers and clinicians often turn to case studies, which provide invaluable insights into the lived experiences of those grappling with social anxiety.

Understanding Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety disorder, also known as social phobia, is characterized by an intense and persistent fear of social situations. Individuals with this condition experience overwhelming anxiety and self-consciousness in everyday social interactions, often fearing negative judgment or embarrassment. The impact of social anxiety extends far beyond mere shyness, significantly interfering with personal relationships, professional opportunities, and overall quality of life.

The prevalence of social anxiety disorder is staggering, affecting an estimated 7% of the global population. This translates to millions of individuals worldwide who struggle with the debilitating effects of this condition. From avoiding social gatherings to experiencing panic attacks in public spaces, the manifestations of social anxiety can be both diverse and profound.

To truly grasp the nuances of social anxiety disorder and develop effective treatment approaches, clinicians and researchers rely heavily on case studies. These in-depth analyses of individual experiences provide a wealth of information that cannot be captured by statistical data alone. By examining specific cases, professionals can identify patterns, explore unique manifestations, and refine treatment strategies to better serve those affected by social anxiety.

Case Study Background: Meet Sarah

In this comprehensive case study analysis, we’ll delve into the experience of Sarah, a 28-year-old marketing professional who has been grappling with social anxiety disorder for over a decade. Sarah’s journey offers valuable insights into the onset, progression, and treatment of this challenging condition.

Sarah grew up in a small town in the Midwest, describing herself as a shy and introverted child. While she had a close-knit group of friends throughout her school years, she often felt uncomfortable in large social gatherings or when required to speak in front of her class. However, it wasn’t until her college years that her anxiety began to escalate significantly.

The onset of Sarah’s more severe social anxiety symptoms coincided with her move to a large university in a bustling city. Suddenly thrust into an environment where she knew no one, Sarah found herself overwhelmed by the constant social interactions required in her new setting. She began experiencing intense physical symptoms, including rapid heartbeat, sweating, and trembling, whenever she had to participate in class discussions or attend social events.

As her symptoms worsened, Sarah sought help from the university’s counseling center. After a thorough assessment process, including interviews, questionnaires, and comprehensive social anxiety disorder tests , Sarah was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder. This diagnosis marked the beginning of her journey towards understanding and managing her condition.

Symptoms and Manifestations

Sarah’s experience with social anxiety disorder manifested in a variety of physical, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms. Physically, she reported experiencing:

1. Rapid heartbeat and palpitations 2. Excessive sweating, particularly on her palms and forehead 3. Trembling or shaking, especially in her hands 4. Nausea and stomach discomfort 5. Difficulty breathing or a sensation of choking

These physical symptoms often intensified in situations where Sarah felt she was being observed or evaluated, such as during presentations at work or when meeting new people.

Cognitively, Sarah’s social anxiety was characterized by persistent negative thought patterns and beliefs. She frequently experienced:

1. Intense fear of judgment or criticism from others 2. Excessive self-consciousness and hyper-awareness of her actions 3. Negative self-talk and self-criticism 4. Catastrophic thinking about potential social failures 5. Difficulty concentrating in social situations due to racing thoughts

These cognitive patterns significantly impacted Sarah’s ability to engage in social interactions and professional activities, often leading to a cycle of avoidance and increased anxiety.

Behaviorally, Sarah developed various avoidance strategies to cope with her anxiety. These included:

1. Declining invitations to social events or gatherings 2. Avoiding eye contact or speaking up in meetings at work 3. Using alcohol as a social lubricant to ease her anxiety 4. Overpreparation for presentations or social interactions to minimize potential mistakes 5. Relying heavily on digital communication to avoid face-to-face interactions

While these avoidance strategies provided temporary relief, they ultimately reinforced Sarah’s anxiety and limited her personal and professional growth.

Treatment Approach

Upon receiving her diagnosis, Sarah began a comprehensive treatment plan that incorporated both psychotherapy and medication management. The primary therapeutic approach used was Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a well-established and effective treatment for social anxiety disorder.

CBT sessions focused on helping Sarah identify and challenge her negative thought patterns and beliefs about social situations. Her therapist employed various techniques, including:

1. Cognitive restructuring to help Sarah recognize and reframe irrational thoughts 2. Mindfulness exercises to increase awareness of her anxiety symptoms and reduce their intensity 3. Role-playing exercises to practice social skills and build confidence 4. Gradual exposure to anxiety-provoking situations in a controlled environment

In addition to CBT, Sarah’s treatment plan included group therapy sessions specifically designed for individuals with social anxiety . These sessions provided a supportive environment where Sarah could practice social interactions and learn from others facing similar challenges.

To address the physical symptoms of her anxiety, Sarah’s psychiatrist prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), which helped reduce the intensity of her anxiety symptoms and improved her overall mood.

A crucial component of Sarah’s treatment was exposure therapy, which involved gradually facing feared social situations in a structured and supported manner. This approach helped Sarah build confidence and develop more adaptive coping strategies. Some exposure exercises included:

1. Initiating conversations with strangers in low-pressure settings 2. Participating in social events without using alcohol as a crutch 3. Volunteering to lead presentations at work 4. Attending networking events in her industry

Throughout her treatment, Sarah also engaged in social skills training to improve her ability to navigate various social situations with greater ease and confidence.

Progress and Outcomes

As Sarah progressed through her treatment, she began to experience significant improvements in her social functioning and overall quality of life. In the short term, she reported:

1. Reduced physical symptoms of anxiety in social situations 2. Increased willingness to engage in social activities 3. Improved performance and confidence at work 4. Better ability to challenge and reframe negative thoughts

Over the long term, Sarah developed more effective strategies for managing her symptoms and maintaining her progress. She continued to practice the skills learned in therapy and gradually expanded her social circle. While she still experienced occasional anxiety in certain situations, she felt better equipped to handle these challenges without resorting to avoidance behaviors.

From Sarah’s perspective, the combination of CBT, medication, and exposure therapy was instrumental in her recovery. She particularly valued the practical skills she gained through therapy, which allowed her to approach social situations with greater confidence and self-compassion.

Analysis and Insights

Sarah’s case study offers valuable insights into the treatment of social anxiety disorder and highlights several key factors contributing to her success:

1. Comprehensive approach: The combination of psychotherapy, medication, and exposure techniques addressed multiple aspects of Sarah’s anxiety.

2. Personalized treatment plan: Sarah’s therapy was tailored to her specific needs and experiences, focusing on the situations that caused her the most distress.

3. Gradual exposure: The step-by-step approach to facing feared situations allowed Sarah to build confidence incrementally.

4. Skill development: Learning practical social skills and cognitive techniques provided Sarah with tools to manage her anxiety in real-world situations.

5. Supportive environment: Group therapy sessions offered a safe space for Sarah to practice social interactions and gain support from peers.

Despite the overall success of Sarah’s treatment, there were challenges encountered along the way. These included:

1. Initial resistance to exposure exercises due to fear of discomfort 2. Difficulty in consistently applying cognitive techniques during high-stress situations 3. Occasional setbacks or temporary increases in anxiety symptoms

Addressing these challenges required patience, persistence, and ongoing support from Sarah’s treatment team.

The insights gained from Sarah’s case have important implications for future social anxiety disorder case studies and treatment approaches. They highlight the need for:

1. Individualized treatment plans that address the unique manifestations of social anxiety in each patient 2. A focus on long-term skill development and coping strategies, rather than just symptom reduction 3. Integration of various therapeutic modalities to address different aspects of the disorder 4. Ongoing support and follow-up to maintain progress and prevent relapse

Sarah’s journey with social anxiety disorder illustrates the complex nature of this condition and the potential for significant improvement with appropriate treatment. Her case underscores the importance of a comprehensive, individualized approach that combines evidence-based therapies, medication when necessary, and ongoing support.

As research in the field of social anxiety continues to evolve, case studies like Sarah’s provide invaluable insights that inform future treatment strategies. They remind us that while social anxiety disorder can be a challenging condition, it is also highly treatable. With the right support and interventions, individuals like Sarah can learn to manage their symptoms effectively and lead fulfilling lives.

Looking ahead, the field of social anxiety research and treatment continues to advance. Emerging areas of focus include:

1. The role of virtual reality in exposure therapy for social anxiety 2. The potential of mindfulness-based interventions in managing anxiety symptoms 3. Exploration of the relationship between social anxiety and related conditions like OCD 4. Investigation into the potential benefits of social anxiety in certain contexts

As our understanding of social anxiety disorder deepens, so too does our ability to provide effective, compassionate care to those affected by this condition. Sarah’s story serves as a testament to the power of perseverance, evidence-based treatment, and the human capacity for growth and change in the face of significant challenges.

For individuals struggling with social anxiety, it’s important to remember that help is available. Whether you’re experiencing high-functioning social anxiety or more severe symptoms, seeking professional support can be a crucial first step towards managing your condition and improving your quality of life. With the right tools and support, it’s possible to navigate the complexities of social anxiety and build a life filled with meaningful connections and personal growth.

References:

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

2. Heimberg, R. G., Brozovich, F. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2010). A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 395-422). Academic Press.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. (2022). Social Anxiety Disorder: More Than Just Shyness. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/social-anxiety-disorder-more-than-just-shyness

4. Stein, M. B., & Stein, D. J. (2008). Social anxiety disorder. The Lancet, 371(9618), 1115-1125.

5. Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69-93). The Guilford Press.

6. Hofmann, S. G., & Otto, M. W. (2017). Cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: Evidence-based and disorder-specific treatment techniques. Routledge.

7. Craske, M. G., Niles, A. N., Burklund, L. J., Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Vilardaga, J. C., Arch, J. J., … & Lieberman, M. D. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for social phobia: Outcomes and moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1034-1048.

8. Goldin, P. R., Morrison, A., Jazaieri, H., Brozovich, F., Heimberg, R., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 427-437.

9. Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2012). Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169-184.

10. Ruscio, A. M., Brown, T. A., Chiu, W. T., Sareen, J., Stein, M. B., & Kessler, R. C. (2008). Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 38(1), 15-28.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

The Complex Relationship Between ADHD and Anxiety: Causes, Symptoms, and…

The Complex Relationship Between ADHD and Anxiety: Understanding Comorbidity and…

The Complex Relationship Between ADHD and Anxiety: Understanding the Connection

ADHD Tweets: Understanding Neurodiversity Through Social Media

ADHD and Driving Anxiety: Navigating the Challenges on the Road

Overcoming Performance Anxiety: How a Therapist Can Help You Succeed

CBD for Performance Anxiety: A Comprehensive Guide to Overcoming Stage…

Comprehensive Guide to Social Anxiety Disorder Tests: Understanding, Identifying, and…

The Anxiety Podcast: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Managing…

Overcoming Social Anxiety and Eye Contact: A Comprehensive Guide

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Editorial: Case reports in anxiety and stress

Ravi philip rajkumar.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited and reviewed by: Marco Grados, Johns Hopkins University, United States

*Correspondence: Ravi Philip Rajkumar [email protected]

Received 2023 Sep 8; Accepted 2023 Sep 12; Collection date 2023.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, comorbidity, prefrontal cortex, culture, trauma, neurostimulation

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Anxiety disorders are a heterogenous group of mental illnesses characterized by fear or anxiety that is excessive and difficult to control, and which is associated with specific maladaptive behaviors ( 1 , 2 ). Anxiety disorders are the most common form of mental illness, affecting almost 46 million people worldwide ( 3 ). The global burden of anxiety disorders has increased by around 50% in the past three decades, despite no significant change in their incidence ( 4 ). This is due to the chronic nature of these disorders: only about 60–70% of patients respond to treatment, and of these, up to two-thirds experience relapses ( 5 , 6 ).

Anxiety disorders can often be triggered or exacerbated by stressful life events ( 7 , 8 ). This is due to the effects of both acute and chronic stress on specific neurotransmitters, neurohormones, and the expression of specific genes ( 9 – 11 ). Stress-related disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are highly comorbid with anxiety disorders ( 12 ). These groups of disorders share common vulnerability genes and molecular pathways ( 13 ), and exposure to traumatic stressors can trigger not just PTSD, but any of the anxiety disorders ( 14 ). This was reflected in earlier classifications that placed anxiety and stress-related disorders in the same general category ( 15 ). Though recent research has identified key differences between them ( 16 ), their overlap remains both conceptually and clinically significant ( 17 ).

From a historical perspective, anxiety and stress-related disorders have often been viewed as “neurotic disorders”, arising from unresolved psychological conflicts, and requiring resolution through psychodynamic therapies ( 18 ). Today, these disorders are viewed as a heterogeneous but interrelated group of conditions, arising from complex interactions between genetic vulnerability, early life experiences, and subsequent stressors ( 19 ). The “final common pathway” for these disorders probably involves mislabeling of environmental stimuli as threats (alarms), misinterpretation of these threats and their consequences (beliefs), and subsequent maladaptive behaviors (coping). The neuroanatomical substrates of these events include the prefrontal cortices, amygdala, hippocampus, insula, and basal ganglia ( 16 , 20 ).

The current Research Topic presents seven papers examining the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of anxiety and stress-related disorders. These reports reflect the diversity of this group of conditions, the clinical challenges faced in treating them, and their relationship to both individual and collective forms of stress and trauma.

Hallucinations are typically associated with psychotic disorders, but they can be a manifestation of significant anxiety or stress ( 21 , 22 ). Jiang et al. report the case of an elderly woman with olfactory hallucinations associated with generalized anxiety disorder. No evidence of a psychotic, neurological or nasopharyngeal disorder was found. The patient's hallucinations resolved with pharmacological management of the anxiety disorder.

Culture can significantly shape the presentation of anxiety disorders by modifying interpretations of specific situations, the health-related consequences attached to them, and the specific illnesses they may represent. This can lead to unusual symptom presentations, particularly in Asian and African cultures ( 23 , 24 ). Religious and spiritual beliefs and practices can also influence anxiety symptomatology ( 25 ). Khoe and Gudi describe the case of a patient with recurrent trance and possession episodes, associated with auditory and visual hallucinations. These symptoms were found to be panic attack equivalents, shaped by religious beliefs and guilt related to a past life event. As in the first case, the patient responded to pharmacological treatment for panic disorders. These cases highlight the challenges involved in diagnosing anxiety disorders across cultures.

Collective forms of trauma are associated with significant increases in anxiety and stress-related disorders ( 26 – 28 ). Limone et al. systematically reviewed the literature on anxiety and stress in students in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. They found high levels of both anxiety symptoms (14–89%) and stress (28–56%) in this population. Risk factors associated with these symptoms included female gender, course of study, social isolation, prior physical or mental illness, and the impact of these disasters on students' families and friends. Kurapov et al. reviewed studies from the first 6 months of the Russia-Ukraine war, and found high levels of both anxiety (36%) and stress (70%) in the Ukrainian general population. Of those with symptoms of anxiety, over one third had severe symptoms suggestive of an anxiety disorder. Risk factors in this population included female gender, older age, financial difficulties, unemployment, forced relocation, and direct experience of war-related trauma. These findings highlight the need for access to adequate mental health care and psychosocial support in conflict and disaster settings.

Anxiety disorders can also be caused by general medical conditions. These “secondary” anxiety disorders should be suspected in patients with atypical symptom presentations ( 29 , 30 ). Geng et al. describe a patient with Cushing's disease, initially misdiagnosed as generalized anxiety disorder. Zhai et al. describe a patient whose anxiety symptoms were found to be related to a patent foramen ovale. In the first of these cases, the patient experienced a severe adverse reaction to standard doses of an SRI. These cases highlight the biological links between anxiety and factors such as cortisol levels ( 31 ) or central perception of suffocation ( 32 ), the importance of identifying and treating the underlying medical disorder, and the need for caution when prescribing psychotropics in medically unstable patients.

Response to standard pharmacological or psychological treatments in anxiety and stress-related disorders is often unsatisfactory ( 5 , 6 , 33 ). Non-invasive neurostimulation methods, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have shown preliminary evidence of efficacy in anxiety disorders and PTSD ( 34 ). Chang et al. describe the successful use of accelerated theta-burst rTMS, applied over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (DLPFC), in a patient with treatment-resistant PTSD occurring in the context of emotional and physical abuse. This result is consistent with the existing literature, and highlights the importance of the DLPFC as a key component of the “executive control” network involved in anxiety and stress responses ( 35 , 36 ).

Overall, the papers included in this Research Topic provide a snapshot of the biological, social, and cultural dimensions of anxiety and stress-related disorders, and will be of interest to clinicians, researchers and public health experts.

Author contributions

RR: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank all the researchers who contributed to this Research Topic.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- 1. Stein DJ, Scott KM, de Jonge P, Kessler RC. Epidemiology from anxiety disorders: from surveys to nosology and back. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2017) 19:127–35. 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.2/dstein [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Lee M, Aggen SH, Otowa T, Castelao E, Preisig M, Grabe HJ, et al. Assessment and characterization of phenotypic heterogeneity of anxiety disorders across five large cohorts. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2016) 25:255–66. 10.1002/mpr.1519 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Yang X, Fang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, Man J, et al. Global, regional and national burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2021) 30:e36. 10.1017/S2045796021000275 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Xiong P, Liu M, Liu B, Hall BJ. Trends in the incidence and DALYs of anxiety disorders at the global, regional, and national levels: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Affect Disord. (2022) 297:83–93. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.022 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Ansell EB, Pinto A, Edelen MO, Markowitz JC, Sanislow CA, Yen S, et al. The association of personality disorders with the prospective 7-year course of anxiety disorders. Psychol Med. (2011) 41:1019–28. 10.1017/S0033291710001777 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Solis EC, van Hemert AM, Carlier IVE, Wardenaar KJ, Schoevers RA, et al. The 9-year clinical course of depressive and anxiety disorders: New NESDA findings. J Affect Disord. (2021) 295:1269–79. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.108 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Moreno-Peral P, Conejo-Ceron S, Motrico E, Rodriguez-Morejon A, Fernandez A, Garcia-Campayo J, et al. Risk factors for the onset of panic and generalised anxiety disorders in the general adult population: a systematic review of cohort studies. J Affect Disord. (2014) 168:337–48. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.021 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. van Honk J, Bos PA, Terbrug D, Heany S, Stein DJ. Neuroendocrine models of social anxiety disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2015) 17:287–93. 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/jhonk [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Knoll AT, Carlezon WA Jr. Dynorphin, stress, and depression. Brain Res. (2010) 1314:56–73. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.074 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Strohle A, Holsboer F. Stress responsive neurohormones in depression and anxiety. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2003) 36:S207–14. 10.1055/s-2003-4513 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Schiele MA, Gottschalk MG, Domschke K. The applied implications of epigenetics in anxiety, affective and stress-related disorders - a review and synthesis on psychosocial stress, psychotherapy and prevention. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 77:101830. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101830 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Longo MSC, Vilete LMP, Figueira I, Quintana MI, Mello MF, Bressan RA, et al. Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder: a population-based study from the two largest cities in Brazil. J Affect Disord. (2020) 263:715–21. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.051 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Smoller JW. The genetics of stress-related disorders: PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2016) 41:297–319. 10.1038/npp.2015.266 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Auxemery Y. Post-traumatic psychiatric disorders: PTSD is not the only diagnosis. Presse Med. (2018) 47:423–30. 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.12.006 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Freyberger HJ, Stieglitz RD, Berner P. Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (section F4) and physiological dysfunction associated with mental or behavioural factors (section F5): results of the ICD-10 field trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. (1990) 23:165–9. 10.1055/s-2007-1014558 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Serra-Blasco M, Radua J, Soriano-Mas C, Gomez-Benlloch A, Porta-Casteras D, Carulla-Roig M, et al. Structural brain correlates in major depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder: a voxel-based morphometry meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2021) 129:269–81. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.07.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Barbano AC, van der Mei WF, deRoon-Cassini TA, Grauer E, Lowe SR, Matsuoka YJ, et al. Differentiating PTSD from anxiety and depression: lessons from the ICD-11 PTSD diagnostic criteria. Depress Anxiety. (2019) 36:490–8. 10.1002/da.22881 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Zerbe KJ. Through the storm: psychoanalytic theory in the psychotherapy of the anxiety disorders. Bull Menninger Clin. (1990) 54:171–83. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Sharma S, Powers A, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. Gene x environment determinants of stress- and anxiety-related disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. (2016) 67:239–61. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033408 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Bystritsky A, Spivak NM, Dang BH, Becerra SA, Distler MG, Jordan SE, et al. Brain circuitry underlying the ABC model of anxiety. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 138:3–14. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.030 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ohayon MM. Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population. Psychiatry Res. (2000) 97:153–64. 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00227-4 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Mertin P, Hartwig S. Auditory hallucinations in nonpsychotic children: diagnostic considerations. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2004) 9:9–14. 10.1046/j.1475-357X.2003.00070.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Hofmann SG, Hinton DE. Cross-cultural aspects of anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2014) 16:450. 10.1007/s11920-014-0450-3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Hinton DE, Park L, Hsia C, Hofmann S, Pollack MH. Anxiety disorder presentations in Asian populations: a review. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2009) 15:295–303. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00095.x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Agorastos A, Demiralay C, Huber CG. Influence of religious aspects and personal beliefs on psychological behavior: focus on anxiety disorders. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2014) 7:93–101. 10.2147/PRBM.S43666 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Jain N, Prasad S, Czarth ZC, Chodnekar SY, Mohan S, Savchenko E, et al. War psychiatry: identifying and managing the neuropsychiatric consequences of armed conflicts. J Prim Care Community Health. (2022) 13:21501319221106625. 10.1177/21501319221106625 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Delpino FM, da Silva CN, Jeronimo JS, Mulling ES, da Cunha LL, Weymar MK, et al. Prevalence of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 2 million people. J Affect Disord. (2022) 318:272–82. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.003 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Beaglehole B, Mulder RT, Frampton CM, Boden JM, Newton-Howes G, Bell CJ. Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2018) 213:716–22. 10.1192/bjp.2018.210 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Cassem EH. Depression and anxiety secondary to medical illness. Psychiatr Clin N Am. (1990) 13:597–612. 10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30338-1 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Testa A, Giannuzzi R, Daini S, Bernardini L, Petrongolo L, Silveri NG. Psychiatric emergencies (part III): psychiatric symptoms resulting from organic diseases. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2013) 17:86–99. Available online at: https://www.europeanreview.org/article/3087 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Zorn JV, Schur RR, Boks MP, Kahn RS, Joels M, Vinkers CH. Cortisol stress reactivity across psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2017) 77:25–36. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.11.036 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Tural U, Iosifescu DV. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of carbon dioxide provocation in psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 143:508–15. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.11.032 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Williams T, Phillips NJ, Stein DJ, Ipser JC. Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2022) 3:CD002795. 10.1002/14651858.cd002795.pub3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Lee HJ, Stein MB. Update on treatments for anxiety-related disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2023) 36:140–5. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000841 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Edinoff AN, Hegefeld TL, Petersen M, Patterson JC, Yossi C, Slizewski J, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:701348. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.701348 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. White LK, Makhoul W, Teferi M, Sheline YI, Balderston NL. The role of dlPFC laterality in the expression and regulation of anxiety. Neuropharmacology. (2023) 224:109355. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109355 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (116.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Case Study of a 17 Year-Old Male An Empirically Supported Treatment Case Study Submitted to the Faculty of the Psychology Department of ... (N = 165) of clinically referred patients with GAD found that 80% of patients no longer met diagnostic criteria for GAD after receiving an intolerance of

The case was approached with the help of cognitive-behavioral therapy, and the patient significantly improved the symptoms of anxiety and depression by the end of the meetings, became more ...

Identify anxiety disorders in case studies; Case Study: Jameela. ... For a patient like Jameela, a combination of CBT and medications is often suggested. At first, Jameela was prescribed the benzodiazepine diazepam, but she did not like the side effect of feeling dull. Next, she was prescribed the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor ...

CASE STUDY Phil (generalized anxiety disorder) Case Study Details. Phil is a 67-year-old male who reports that his biggest problem is worrying. He worries all of the time and about "everything under the sun." For example, he reports equal worry about his wife who is undergoing treatment for breast cancer and whether he returned his book to ...

The patient in the case study reported many clinical symptoms that can be misinterpreted for musculoskeletal deficits. Physical therapy cannot directly cure anxiety, since it is thought to be caused by neurotransmitters within the brain. However, physical therapists can help those who suffer from GAD be aware of their anxiety.

This article serves as the clinical case example for the subsequent series of papers in this cognitive-behavioral case conference on the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). The present case does not include a case conceptualization, but is rather a detailed description of a client's assessment results through the illustration of ...

GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER CASE STUDY 73 wrong. The patient had also been worried with thoughts of being a failure, inability to cope like others, and worry of making a fool of himself. The score on the second subscale was 20 which indicates that patient had also been worried about his health. Whereas, the patient

The present study is aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of a Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy (MBCBT) for reducing cognitive and somatic anxiety and modifying dysfunctional cognitions in patients with anxiety disorders. A single case ...

The insights gained from Sarah's case have important implications for future social anxiety disorder case studies and treatment approaches. They highlight the need for: 1. Individualized treatment plans that address the unique manifestations of social anxiety in each patient 2. A focus on long-term skill ...

As in the first case, the patient responded to pharmacological treatment for panic disorders. These cases highlight the challenges involved in diagnosing anxiety disorders across cultures. ... Kurapov et al. reviewed studies from the first 6 months of the Russia-Ukraine war, and found high levels of both anxiety (36%) and stress (70%) in the ...