What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay + Example

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered

What is the ap lit prose essay, how will ap scores affect my college chances.

AP Literature and Composition (AP Lit), not to be confused with AP English Language and Composition (AP Lang), teaches students how to develop the ability to critically read and analyze literary texts. These texts include poetry, prose, and drama. Analysis is an essential component of this course and critical for the educational development of all students when it comes to college preparation. In this course, you can expect to see an added difficulty of texts and concepts, similar to the material one would see in a college literature course.

While not as popular as AP Lang, over 380,136 students took the class in 2019. However, the course is significantly more challenging, with only 49.7% of students receiving a score of three or higher on the exam. A staggeringly low 6.2% of students received a five on the exam.

The AP Lit exam is similar to the AP Lang exam in format, but covers different subject areas. The first section is multiple-choice questions based on five short passages. There are 55 questions to be answered in 1 hour. The passages will include at least two prose fiction passages and two poetry passages and will account for 45% of your total score. All possible answer choices can be found within the text, so you don’t need to come into the exam with prior knowledge of the passages to understand the work.

The second section contains three free-response essays to be finished in under two hours. This section accounts for 55% of the final score and includes three essay questions: the poetry analysis essay, the prose analysis essay, and the thematic analysis essay. Typically, a five-paragraph format will suffice for this type of writing. These essays are scored holistically from one to six points.

Today we will take a look at the AP Lit prose essay and discuss tips and tricks to master this section of the exam. We will also provide an example of a well-written essay for review.

The AP Lit prose essay is the second of the three essays included in the free-response section of the AP Lit exam, lasting around 40 minutes in total. A prose passage of approximately 500 to 700 words and a prompt will be given to guide your analytical essay. Worth about 18% of your total grade, the essay will be graded out of six points depending on the quality of your thesis (0-1 points), evidence and commentary (0-4 points), and sophistication (0-1 points).

While this exam seems extremely overwhelming, considering there are a total of three free-response essays to complete, with proper time management and practiced skills, this essay is manageable and straightforward. In order to enhance the time management aspect of the test to the best of your ability, it is essential to understand the following six key concepts.

1. Have a Clear Understanding of the Prompt and the Passage

Since the prose essay is testing your ability to analyze literature and construct an evidence-based argument, the most important thing you can do is make sure you understand the passage. That being said, you only have about 40 minutes for the whole essay so you can’t spend too much time reading the passage. Allot yourself 5-7 minutes to read the prompt and the passage and then another 3-5 minutes to plan your response.

As you read through the prompt and text, highlight, circle, and markup anything that stands out to you. Specifically, try to find lines in the passage that could bolster your argument since you will need to include in-text citations from the passage in your essay. Even if you don’t know exactly what your argument might be, it’s still helpful to have a variety of quotes to use depending on what direction you take your essay, so take note of whatever strikes you as important. Taking the time to annotate as you read will save you a lot of time later on because you won’t need to reread the passage to find examples when you are in the middle of writing.

Once you have a good grasp on the passage and a solid array of quotes to choose from, you should develop a rough outline of your essay. The prompt will provide 4-5 bullets that remind you of what to include in your essay, so you can use these to structure your outline. Start with a thesis, come up with 2-3 concrete claims to support your thesis, back up each claim with 1-2 pieces of evidence from the text, and write a brief explanation of how the evidence supports the claim.

2. Start with a Brief Introduction that Includes a Clear Thesis Statement

Having a strong thesis can help you stay focused and avoid tangents while writing. By deciding the relevant information you want to hit upon in your essay up front, you can prevent wasting precious time later on. Clear theses are also important for the reader because they direct their focus to your essential arguments.

In other words, it’s important to make the introduction brief and compact so your thesis statement shines through. The introduction should include details from the passage, like the author and title, but don’t waste too much time with extraneous details. Get to the heart of your essay as quick as possible.

3. Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument

One of the requirements AP Lit readers are looking for is your use of evidence. In order to satisfy this aspect of the rubric, you should make sure each body paragraph has at least 1-2 pieces of evidence, directly from the text, that relate to the claim that paragraph is making. Since the prose essay tests your ability to recognize and analyze literary elements and techniques, it’s often better to include smaller quotes. For example, when writing about the author’s use of imagery or diction you might pick out specific words and quote each word separately rather than quoting a large block of text. Smaller quotes clarify exactly what stood out to you so your reader can better understand what are you saying.

Including smaller quotes also allows you to include more evidence in your essay. Be careful though—having more quotes is not necessarily better! You will showcase your strength as a writer not by the number of quotes you manage to jam into a paragraph, but by the relevance of the quotes to your argument and explanation you provide. If the details don’t connect, they are merely just strings of details.

4. Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Evidence to Your Argument

As the previous tip explained, citing phrases and words from the passage won’t get you anywhere if you don’t provide an explanation as to how your examples support the claim you are making. After each new piece of evidence is introduced, you should have a sentence or two that explains the significance of this quote to the piece as a whole.

This part of the paragraph is the “So what?” You’ve already stated the point you are trying to get across in the topic sentence and shared the examples from the text, so now show the reader why or how this quote demonstrates an effective use of a literary technique by the author. Sometimes students can get bogged down by the discussion and lose sight of the point they are trying to make. If this happens to you while writing, take a step back and ask yourself “Why did I include this quote? What does it contribute to the piece as a whole?” Write down your answer and you will be good to go.

5. Write a Brief Conclusion

While the critical part of the essay is to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs, a conclusion provides a satisfying ending to the essay and the last opportunity to drive home your argument. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of extra time spent in the preceding paragraphs, do not worry, as that is not fatal to your score.

Without repeating your thesis statement word for word, find a way to return to the thesis statement by summing up your main points. This recap reinforces the arguments stated in the previous paragraphs, while all of the preceding paragraphs successfully proved the thesis statement.

6. Don’t Forget About Your Grammar

Though you will undoubtedly be pressed for time, it’s still important your essay is well-written with correct punctuating and spelling. Many students are able to write a strong thesis and include good evidence and commentary, but the final point on the rubric is for sophistication. This criteria is more holistic than the former ones which means you should have elevated thoughts and writing—no grammatical errors. While a lack of grammatical mistakes alone won’t earn you the sophistication point, it will leave the reader with a more favorable impression of you.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

[amp-cta id="9459"]

Here are Nine Must-have Tips and Tricks to Get a Good Score on the Prose Essay:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key instruction s in the prompt.

- Briefly outlin e what you want to cover in your essay.

- Be sure to have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title in your introduction. Refer to characters by name.

- Quality over quantity when it comes to picking quotes! Better to have a smaller number of more detailed quotes than a large amount of vague ones.

- Fully explain how each piece of evidence supports your thesis .

- Focus on the literary techniques in the passage and avoid summarizing the plot.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

Here is an example essay from 2020 that received a perfect 6:

[1] In this passage from a 1912 novel, the narrator wistfully details his childhood crush on a girl violinist. Through a motif of the allure of musical instruments, and abundant sensory details that summon a vivid image of the event of their meeting, the reader can infer that the narrator was utterly enraptured by his obsession in the moment, and upon later reflection cannot help but feel a combination of amusement and a resummoning of the moment’s passion.

[2] The overwhelming abundance of hyper-specific sensory details reveals to the reader that meeting his crush must have been an intensely powerful experience to create such a vivid memory. The narrator can picture the “half-dim church”, can hear the “clear wail” of the girl’s violin, can see “her eyes almost closing”, can smell a “faint but distinct fragrance.” Clearly, this moment of discovery was very impactful on the boy, because even later he can remember the experience in minute detail. However, these details may also not be entirely faithful to the original experience; they all possess a somewhat mysterious quality that shows how the narrator may be employing hyperbole to accentuate the girl’s allure. The church is “half-dim”, the eyes “almost closing” – all the details are held within an ethereal state of halfway, which also serves to emphasize that this is all told through memory. The first paragraph also introduces the central conciet of music. The narrator was drawn to the “tones she called forth” from her violin and wanted desperately to play her “accompaniment.” This serves the double role of sensory imagery (with the added effect of music being a powerful aural image) and metaphor, as the accompaniment stands in for the narrator’s true desire to be coupled with his newfound crush. The musical juxtaposition between the “heaving tremor of the organ” and the “clear wail” of her violin serves to further accentuate how the narrator percieved the girl as above all other things, as high as an angel. Clearly, the memory of his meeting his crush is a powerful one that left an indelible impact on the narrator.

[3] Upon reflecting on this memory and the period of obsession that followed, the narrator cannot help but feel amused at the lengths to which his younger self would go; this is communicated to the reader with some playful irony and bemused yet earnest tone. The narrator claims to have made his “first and last attempts at poetry” in devotion to his crush, and jokes that he did not know to be “ashamed” at the quality of his poetry. This playful tone pokes fun at his childhood self for being an inexperienced poet, yet also acknowledges the very real passion that the poetry stemmed from. The narrator goes on to mention his “successful” endeavor to conceal his crush from his friends and the girl; this holds an ironic tone because the narrator immediately admits that his attempts to hide it were ill-fated and all parties were very aware of his feelings. The narrator also recalls his younger self jumping to hyperbolic extremes when imagining what he would do if betrayed by his love, calling her a “heartless jade” to ironically play along with the memory. Despite all this irony, the narrator does also truly comprehend the depths of his past self’s infatuation and finds it moving. The narrator begins the second paragraph with a sentence that moves urgently, emphasizing the myriad ways the boy was obsessed. He also remarks, somewhat wistfully, that the experience of having this crush “moved [him] to a degree which now [he] can hardly think of as possible.” Clearly, upon reflection the narrator feels a combination of amusement at the silliness of his former self and wistful respect for the emotion that the crush stirred within him.

[4] In this passage, the narrator has a multifaceted emotional response while remembering an experience that was very impactful on him. The meaning of the work is that when we look back on our memories (especially those of intense passion), added perspective can modify or augment how those experiences make us feel

More essay examples, score sheets, and commentaries can be found at College Board .

While AP Scores help to boost your weighted GPA, or give you the option to get college credit, AP Scores don’t have a strong effect on your admissions chances . However, colleges can still see your self-reported scores, so you might not want to automatically send scores to colleges if they are lower than a 3. That being said, admissions officers care far more about your grade in an AP class than your score on the exam.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay with Examples

March 30, 2024

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples – The College Board’s Advanced Placement Literature and Composition Course is one of the most enriching experiences that high school students can have. It exposes you to literature that most people don’t encounter until college , and it helps you develop analytical and critical thinking skills that will enhance the quality of your life, both inside and outside of school. The AP Lit Exam reflects the rigor of the course. The exam uses consistent question types, weighting, and scoring parameters each year . This means that, as you prepare for the exam, you can look at previous questions, responses, score criteria, and scorer commentary to help you practice until your essays are perfect.

What is the AP Lit Free Response testing?

In AP Literature, you read books, short stories, and poetry, and you learn how to commit the complex act of literary analysis . But what does that mean? Well, “to analyze” literally means breaking a larger idea into smaller and smaller pieces until the pieces are small enough that they can help us to understand the larger idea. When we’re performing literary analysis, we’re breaking down a piece of literature into smaller and smaller pieces until we can use those pieces to better understand the piece of literature itself.

So, for example, let’s say you’re presented with a passage from a short story to analyze. The AP Lit Exam will ask you to write an essay with an essay with a clear, defensible thesis statement that makes an argument about the story, based on some literary elements in the short story. After reading the passage, you might talk about how foreshadowing, allusion, and dialogue work together to demonstrate something essential in the text. Then, you’ll use examples of each of those three literary elements (that you pull directly from the passage) to build your argument. You’ll finish the essay with a conclusion that uses clear reasoning to tell your reader why your argument makes sense.

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples (Continued)

But what’s the point of all of this? Why do they ask you to write these essays?

Well, the essay is, once again, testing your ability to conduct literary analysis. However, the thing that you’re also doing behind that literary analysis is a complex process of both inductive and deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning takes a series of points of evidence and draws a larger conclusion. Deductive reasoning departs from the point of a broader premise and draws a singular conclusion. In an analytical essay like this one, you’re using small pieces of evidence to draw a larger conclusion (your thesis statement) and then you’re taking your thesis statement as a larger premise from which you derive your ultimate conclusion.

So, the exam scorers are looking at your ability to craft a strong thesis statement (a singular sentence that makes an argument), use evidence and reasoning to support that argument, and then to write the essay well. This is something they call “sophistication,” but they’re looking for well-organized thoughts carried through clear, complete sentences.

This entire process is something you can and will use throughout your life. Law, engineering, medicine—whatever pursuit, you name it—utilizes these forms of reasoning to run experiments, build cases, and persuade audiences. The process of this kind of clear, analytical thinking can be honed, developed, and made easier through repetition.

Practice Makes Perfect

Because the AP Literature Exam maintains continuity across the years, you can pull old exam copies, read the passages, and write responses. A good AP Lit teacher is going to have you do this time and time again in class until you have the formula down. But, it’s also something you can do on your own, if you’re interested in further developing your skills.

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples

Let’s take a look at some examples of questions, answers and scorer responses that will help you to get a better idea of how to craft your own AP Literature exam essays.

In the exam in 2023, students were asked to read a poem by Alice Cary titled “Autumn,” which was published in 1874. In it, the speaker contemplates the start of autumn. Then, students are asked to craft a well-written essay which uses literary techniques to convey the speaker’s complex response to the changing seasons.

The following is an essay that received a perfect 6 on the exam. There are grammar and usage errors throughout the essay, which is important to note: even though the writer makes some mistakes, the structure and form of their argument was strong enough to merit a 6. This is what your scorers will be looking for when they read your essay.

Example Essay

Romantic and hyperbolic imagery is used to illustrate the speaker’s unenthusiastic opinion of the coming of autumn, which conveys Cary’s idea that change is difficult to accept but necessary for growth.

Romantic imagery is utilized to demonstrate the speaker’s warm regard for the season of summer and emphasize her regretfulness for autumn’s coming, conveying the uncomfortable change away from idyllic familiarity. Summer, is portrayed in the image of a woman who “from her golden collar slips/and strays through stubble fields/and moans aloud.” Associated with sensuality and wealth, the speaker implies the interconnection between a season and bounty, comfort, and pleasure. Yet, this romantic view is dismantled by autumn, causing Summer to “slip” and “stray through stubble fields.” Thus, the coming of real change dethrones a constructed, romantic personification of summer, conveying the speaker’s reluctance for her ideal season to be dethroned by something much less decorated and adored.

Summer, “she lies on pillows of the yellow leaves,/ And tries the old tunes for over an hour”, is contrasted with bright imagery of fallen leaves/ The juxtaposition between Summer’s character and the setting provides insight into the positivity of change—the yellow leaves—by its contrast with the failures of attempting to sustain old habits or practices, “old tunes”. “She lies on pillows” creates a sympathetic, passive image of summer in reaction to the coming of Autumn, contrasting her failures to sustain “old tunes.” According to this, it is understood that the speaker recognizes the foolishness of attempting to prevent what is to come, but her wishfulness to counter the natural progression of time.

Hyperbolic imagery displays the discrepancies between unrealistic, exaggerated perceptions of change and the reality of progress, continuing the perpetuation of Cary’s idea that change must be embraced rather than rejected. “Shorter and shorter now the twilight clips/The days, as though the sunset gates they crowd”, syntax and diction are used to literally separate different aspects of the progression of time. In an ironic parallel to the literal language, the action of twilight’s “clip” and the subject, “the days,” are cut off from each other into two different lines, emphasizing a sense of jarring and discomfort. Sunset, and Twilight are named, made into distinct entities from the day, dramatizing the shortening of night-time into fall. The dramatic, sudden implications for the change bring to mind the switch between summer and winter, rather than a transitional season like fall—emphasizing the Speaker’s perspective rather than a factual narration of the experience.

She says “the proud meadow-pink hangs down her head/Against the earth’s chilly bosom, witched with frost”. Implying pride and defeat, and the word “witched,” the speaker brings a sense of conflict, morality, and even good versus evil into the transition between seasons. Rather than a smooth, welcome change, the speaker is practically against the coming of fall. The hyperbole present in the poem serves to illustrate the Speaker’s perspective and ideas on the coming of fall, which are characterized by reluctance and hostility to change from comfort.

The topic of this poem, Fall–a season characterized by change and the deconstruction of the spring and summer landscape—is juxtaposed with the final line which evokes the season of Spring. From this, it is clear that the speaker appreciates beautiful and blossoming change. However, they resent that which destroys familiar paradigms and norms. Fall, seen as the death of summer, is characterized as a regression, though the turning of seasons is a product of the literal passage of time. Utilizing romantic imagery and hyperbole to shape the Speaker’s perspective, Cary emphasizes the need to embrace change though it is difficult, because growth is not possible without hardship or discomfort.

Scoring Criteria: Why did this essay do so well?

When it comes to scoring well, there are some rather formulaic things that the judges are searching for. You might think that it’s important to “stand out” or “be creative” in your writing. However, aside from concerns about “sophistication,” which essentially means you know how to organize thoughts into sentences and you can use language that isn’t entirely elementary, you should really focus on sticking to a form. This will show the scorers that you know how to follow that inductive/deductive reasoning process that we mentioned earlier, and it will help to present your ideas in the most clear, coherent way possible to someone who is reading and scoring hundreds of essays.

So, how did this essay succeed? And how can you do the same thing?

First: The Thesis

On the exam, you can either get one point or zero points for your thesis statement. The scorers said, “The essay responds to the prompt with a defensible thesis located in the introductory paragraph,” which you can read as the first sentence in the essay. This is important to note: you don’t need a flowery hook to seduce your reader; you can just start this brief essay with some strong, simple, declarative sentences—or go right into your thesis.

What makes a good thesis? A good thesis statement does the following things:

- Makes a claim that will be supported by evidence

- Is specific and precise in its use of language

- Argues for an original thought that goes beyond a simple restating of the facts

If you’re sitting here scratching your head wondering how you come up with a thesis statement off the top of your head, let me give you one piece of advice: don’t.

The AP Lit scoring criteria gives you only one point for the thesis for a reason: they’re just looking for the presence of a defensible claim that can be proven by evidence in the rest of the essay.

Second: Write your essay from the inside out

While the thesis is given one point, the form and content of the essay can receive anywhere from zero to four points. This is where you should place the bulk of your focus.

My best advice goes like this:

- Choose your evidence first

- Develop your commentary about the evidence

- Then draft your thesis statement based on the evidence that you find and the commentary you can create.

It will seem a little counterintuitive: like you’re writing your essay from the inside out. But this is a fundamental skill that will help you in college and beyond. Don’t come up with an argument out of thin air and then try to find evidence to support your claim. Look for the evidence that exists and then ask yourself what it all means. This will also keep you from feeling stuck or blocked at the beginning of the essay. If you prepare for the exam by reviewing the literary devices that you learned in the course and practice locating them in a text, you can quickly and efficiently read a literary passage and choose two or three literary devices that you can analyze.

Third: Use scratch paper to quickly outline your evidence and commentary

Once you’ve located two or three literary devices at work in the given passage, use scratch paper to draw up a quick outline. Give each literary device a major bullet point. Then, briefly point to the quotes/evidence you’ll use in the essay. Finally, start to think about what the literary device and evidence are doing together. Try to answer the question: what meaning does this bring to the passage?

A sample outline for one paragraph of the above essay might look like this:

Romantic imagery

Portrayal of summer

- Woman who “from her golden collar… moans aloud”

- Summer as bounty

Contrast with Autumn

- Autumn dismantles Summer

- “Stray through stubble fields”

- Autumn is change; it has the power to dethrone the romance of Summer/make summer a bit meaningless

Recognition of change in a positive light

- Summer “lies on pillows / yellow leaves / tries old tunes”

- Bright imagery/fallen leaves

- Attempt to maintain old practices fails: “old tunes”

- But! There is sympathy: “lies on pillows”

Speaker recognizes: she can’t prevent what is to come; wishes to embrace natural passage of time

By the time the writer gets to the end of the outline for their paragraph, they can easily start to draw conclusions about the paragraph based on the evidence they have pulled out. You can see how that thinking might develop over the course of the outline.

Then, the speaker would take the conclusions they’ve drawn and write a “mini claim” that will start each paragraph. The final bullet point of this outline isn’t the same as the mini claim that comes at the top of the second paragraph of the essay, however, it is the conclusion of the paragraph. You would do well to use the concluding thoughts from your outline as the mini claim to start your body paragraph. This will make your paragraphs clear, concise, and help you to construct a coherent argument.

Repeat this process for the other one or two literary devices that you’ve chosen to analyze, and then: take a step back.

Fourth: Draft your thesis

Once you quickly sketch out your outline, take a moment to “stand back” and see what you’ve drafted. You’ll be able to see that, among your two or three literary devices, you can draw some commonality. You might be able to say, as the writer did here, that romantic and hyperbolic imagery “illustrate the speaker’s unenthusiastic opinion of the coming of autumn,” ultimately illuminating the poet’s idea “that change is difficult to accept but necessary for growth.”

This is an original argument built on the evidence accumulated by the student. It directly answers the prompt by discussing literary techniques that “convey the speaker’s complex response to the changing seasons.” Remember to go back to the prompt and see what direction they want you to head with your thesis, and craft an argument that directly speaks to that prompt.

Then, move ahead to finish your body paragraphs and conclusion.

Fifth: Give each literary device its own body paragraph

In this essay, the writer examines the use of two literary devices that are supported by multiple pieces of evidence. The first is “romantic imagery” and the second is “hyperbolic imagery.” The writer dedicates one paragraph to each idea. You should do this, too.

This is why it’s important to choose just two or three literary devices. You really don’t have time to dig into more. Plus, more ideas will simply cloud the essay and confuse your reader.

Using your outline, start each body paragraph with a “mini claim” that makes an argument about what it is you’ll be saying in your paragraph. Lay out your pieces of evidence, then provide commentary for why your evidence proves your point about that literary device.

Move onto the next literary device, rinse, and repeat.

Sixth: Commentary and Conclusion

Finally, you’ll want to end this brief essay with a concluding paragraph that restates your thesis, briefly touches on your most important points from each body paragraph, and includes a development of the argument that you laid out in the essay.

In this particular example essay, the writer concludes by saying, “Utilizing romantic imagery and hyperbole to shape the Speaker’s perspective, Cary emphasizes the need to embrace change though it is difficult, because growth is not possible without hardship or discomfort.” This is a direct restatement of the thesis. At this point, you’ll have reached the end of your essay. Great work!

Seventh: Sophistication

A final note on scoring criteria: there is one point awarded to what the scoring criteria calls “sophistication.” This is evidenced by the sophistication of thought and providing a nuanced literary analysis, which we’ve already covered in the steps above.

There are some things to avoid, however:

- Sweeping generalizations, such as, “From the beginning of human history, people have always searched for love,” or “Everyone goes through periods of darkness in their lives, much like the writer of this poem.”

- Only hinting at possible interpretations instead of developing your argument

- Oversimplifying your interpretation

- Or, by contrast, using overly flowery or complex language that does not meet your level of preparation or the context of the essay.

Remember to develop your argument with nuance and complexity and to write in a style that is academic but appropriate for the task at hand.

If you want more practice or to check out other exams from the past, go to the College Board’s website .

Brittany Borghi

After earning a BA in Journalism and an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from the University of Iowa, Brittany spent five years as a full-time lecturer in the Rhetoric Department at the University of Iowa. Additionally, she’s held previous roles as a researcher, full-time daily journalist, and book editor. Brittany’s work has been featured in The Iowa Review, The Hopkins Review, and the Pittsburgh City Paper, among others, and she was also a 2021 Pushcart Prize nominee.

- 2-Year Colleges

- ADHD/LD/Autism/Executive Functioning

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- General Knowledge

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Middle School Success

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

$2,000 No Essay Scholarship

Presented by College Transitions

- Win $2,000 for college • 1 minute or less to enter • No essay required • Open to students and parents in the U.S.

Create your account today and easily enter all future sweepstakes!

Enter to Win $2,000 Today!

Definition of Prose

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it.

Common Examples of First Prose Lines in Well-Known Novels

Examples of famous lines of prose, types of prose, difference between prose and poetry, writing a prose poem, prose edda vs. poetic edda, examples of prose in literature, example 1: the grapes of wrath by john steinbeck.

A large drop of sun lingered on the horizon and then dripped over and was gone, and the sky was brilliant over the spot where it had gone, and a torn cloud, like a bloody rag, hung over the spot of its going. And dusk crept over the sky from the eastern horizon, and darkness crept over the land from the east.

Example 2: This Is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams

I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold

Example 3: Harrison Bergeron by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

The year was 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

Synonyms of Prose

Post navigation.

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, ap lit prose essay examples and strategies.

Hello! I'm trying to study for the AP Lit prose essay and could really use some example essays to help me revise. Do any of you know good sources? Also, any strategies on how to approach this type of essay would be incredibly helpful. Thanks so much!

For the AP Lit prose essay, the first thing you want to do is to clearly understand what the prompt is asking. Take time to read the prompt and the prose passage carefully. Is the prompt asking for characterization, themes, point of view, etc? Jot down your understanding of the text's central ideas.

While you're reading the prose passage, actively annotate. Circle key words, underline significant phrases, and jot down thoughts in the margins. This helps you extract as much information from the passage as possible, and it will make referencing parts of the passage easier later.

When writing your essay, structure is key. Your essay should include an introduction, body, and conclusion.

In the introduction, state the author's purpose as provided in the prompt and provide a thesis statement that explains how the author accomplishes this purpose.

The body paragraphs should each analyze a unique literary device or technique the author uses to accomplish their purpose. Always ensure to include specific textual evidence (quoting directly from the passage) to support your claims.

Then, in your conclusion, restate your thesis but in different words. You might want to briefly recap how the literary devices you discussed contribute to the overall theme or message.

Regarding examples of prose essays, it's a good idea to browse through CollegeBoard's AP Central, the official online home of the AP Program. They provide examples of student responses and scoring commentaries that can help you understand what is required for a high-scoring response.

Lastly, one of the most important things you can do to prep for this part of the exam is to read a lot of prose in varied styles and genres. This way, you get familiar with different ways of characterization, tone, setting, and symbol usage. Practice the analysis strategies you've learned on these works.

Remember, as much as this is an essay about a text, it's also an essay about your analysis. It's important to not just identify a theme or technique, but to delve into how and why the author is using it. So use your own voice and your own argument in each sentence. Good luck!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

AP® English Literature

How to get a 9 on prose analysis frq in ap® english literature.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

When it’s time to take the AP® English Literature and Composition exam, will you be ready? If you’re aiming high, you’ll want to know the best route to a five on the AP® exam. You know the exam is going to be tough, so how do prepare for success? To do well on the AP® English Literature and Composition exam, you’ll need to score high on the essays. For that, you’ll need to write a competent, efficient essay that argues an accurate interpretation of the work under examination in the Free Response Question section.

The AP® English Literature and Composition exam consists of two sections, the first being a 55-question multiple choice portion worth 45% of the total test grade. This section tests your ability to read drama, verse, or prose fiction excerpts and answer questions about them. The second section, worth 55% of the total score, requires essay responses to three questions demonstrating your ability to analyze literary works. You’ll have to discuss a poem analysis, a prose fiction passage analysis, and a concept, issue, or element analysis of a literary work–in two hours.

Before the exam, you should know how to construct a clear, organized essay that defends a focused claim about the work under analysis. You must write a brief introduction that includes the thesis statement, followed by body paragraphs that further the thesis statement with detailed, thorough support, and a short concluding paragraph that reiterates and reinforces the thesis statement without repeating it. Clear organization, specific support, and full explanations or discussions are three critical components of high-scoring essays.

General Tips to Bettering Your Odds at a Nine on the AP® English Literature Prose FRQ

You may know already how to approach the prose analysis, but don’t forget to keep the following in mind coming into the exam:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key to-do’s in the prompt.

- Briefly outline where you’re going to hit each prompt item — in other words, pencil out a specific order.

- Be sure you have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title of the prose selection in your thesis statement. Refer to characters by name.

- Use quotes — lots of them — to exemplify the elements and your argument points throughout the essay.

- Fully explain or discuss how your examples support your thesis. A deeper, fuller, and more focused explanation of fewer elements is better than a shallow discussion of more elements (shotgun approach).

- Avoid vague, general statements or merely summarizing the plot instead of clearly focusing on the prose passage itself.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Write in the present tense with generally good grammar.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

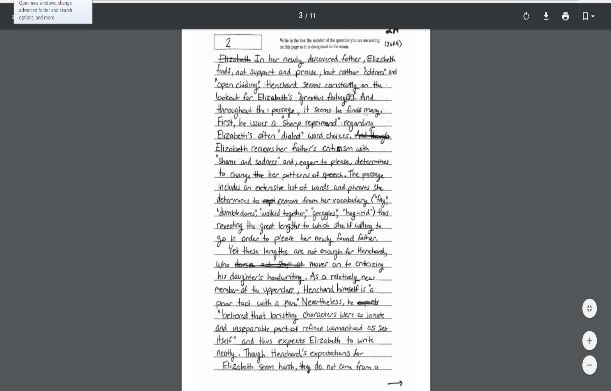

The newly-released 2016 sample AP® English Literature and Composition exam questions, sample responses, and grading rubrics provide a valuable opportunity to analyze how to achieve high scores on each of the three Section II FRQ responses. However, for purposes of this examination, the Prose Analysis FRQ strategies will be the focus. The prose selection for analysis in last year’s exam was Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge , a 19th-century novel. Exam takers had to respond to the following instructions:

- Analyze the complex relationship between the two characters Hardy portrays in the passage.

- Pay attention to tone, word choice, and detail selection.

- Write a well-written essay.

For a clear understanding of the components of a model essay, you’ll find it helpful to analyze and compare all three sample answers provided by the CollegeBoard: the high scoring (A) essay, the mid-range scoring (B) essay, and the low scoring (C) essay. All three provide a lesson for you: to achieve a nine on the prose analysis essay, model the ‘A’ essay’s strengths and avoid the weaknesses of the other two.

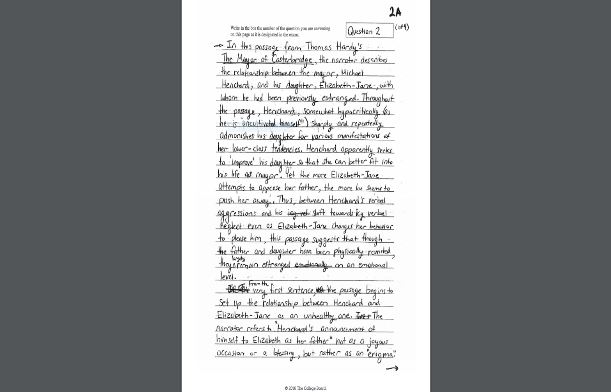

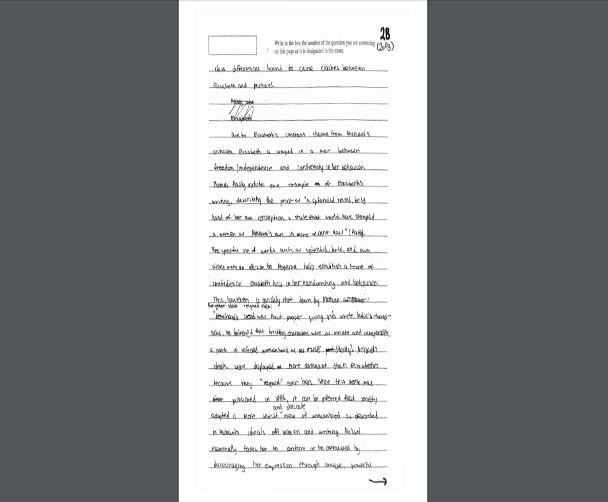

Start with a Succinct Introduction that Includes Your Thesis Statement

The first sample essay (A) begins with a packed first sentence: the title of the work, author, named characters, and the subject alluded to in the prompt that will form the foundation of the upcoming argument — the strained relationship between father and daughter. Then, after summarizing the context of the passage — that tense relationship — the student quotes relevant phrases (“lower-class”, “verbal aggressions”) that depict the behavior and character of each.

By packing each sentence efficiently with details (“uncultivated”, “hypocritical”) on the way to the thesis statement, the writer controls the argument by folding in only the relevant details that support the claim at the end of the introduction: though reunited physically, father and daughter remain separated emotionally. The writer wastes no words and quickly directs the reader’s focus to the characters’ words and actions that define their estranged relationship. From the facts cited, the writer’s claim or thesis is logical.

The mid-range B essay introduction also mentions the title, author, and relationship (“strange relationship”) that the instructions direct the writer to examine. However, the student neither names the characters nor identifies what’s “strange” about the relationship. The essay needs more specific details to clarify the complexity in the relationship. Instead, the writer merely hints at that complexity by stating father and daughter “try to become closer to each other’s expectations”. There’s no immediately clear correlation between the “reunification” and the expectations. Finally, the student wastes time and space in the first two sentences with a vague platitude for an “ice breaker” to start the essay. It serves no other function.

The third sample lacks cohesiveness, focus, and a clear thesis statement. The first paragraph introduces the writer’s feelings about the characters and how the elements in the story helped the student analyze, both irrelevant to the call of the instructions. The introduction gives no details of the passage: no name, title, characters, or relationship. The thesis statement is shallow–the daughter was better off before she reunited with her father–as it doesn’t even hint at the complexity of the relationship. The writer merely parrots the prompt instructions about “complex relationship” and “speaker’s tone, word choice, and selection of detail”.

In sum, make introductions brief and compact. Use specific details from the passage that support a logical thesis statement which clearly directs the argument and addresses the instructions’ requirements. Succinct writing helps. Pack your introduction with specific excerpt details, and don’t waste time on sentences that don’t do the work ahead for you. Be sure the thesis statement covers all of the relevant facts of the passage for a cohesive argument.

Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument Points

The A answer supports the thesis by qualifying the relationship as unhealthy in the first sentence. Then the writer includes the quoted examples that contrast what one would expect characterizes a father-daughter relationship — joyous, blessing, support, praise — against the reality of Henchard and Elizabeth’s relationship: “enigma”, “coldness”, and “open chiding”.

These and other details in the thorough first body paragraph leave nothing for the reader to misunderstand. The essayist proves the paragraph’s main idea with numerous examples. The author controls the first argument point that the relationship is unhealthy by citing excerpted words and actions of the two characters demonstrating the father’s aggressive disapproval and the daughter’s earnestness and shame.

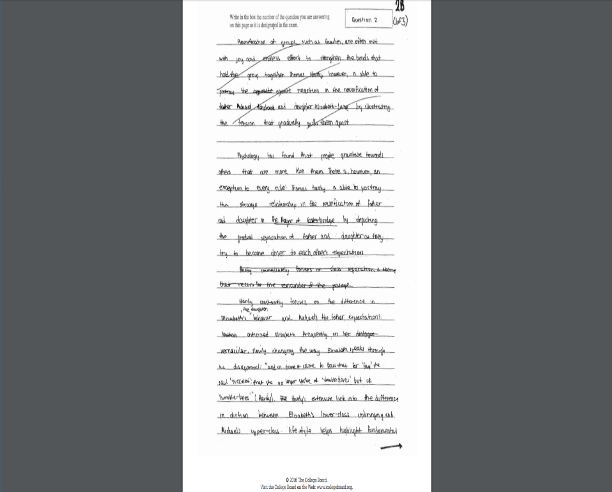

The second and third body paragraphs not only add more proof of the strained relationship in the well-chosen example of the handwriting incident but also explore the underlying motives of the father. In suggesting the father has good intentions despite his outward hostility, the writer proposes that Henchard wants to elevate his long-lost daughter. Henchard’s declaration that handwriting “with bristling characters” defines refinement in a woman both diminishes Elizabeth and reveals his silent hope for her, according to the essayist. This contradiction clearly proves the relationship is “complex”.

The mid-range sample also cites specific details: the words Elizabeth changes (“fay” for “succeed”) for her father. These details are supposed to support the point that class difference causes conflict between the two. However, the writer leaves it to the reader to make the connection between class, expectations, and word choices. The example of the words Elizabeth eliminates from her vocabulary does not illustrate the writer’s point of class conflict. In fact, the class difference as the cause of their difficulties is never explicitly stated. Instead, the writer makes general, unsupported statements about Hardy’s focus on the language difference without saying why Hardy does that.

Like the A essay, sample C also alludes to the handwriting incident but only to note that the description of Henchard turning red is something the reader can imagine. In fact, the writer gives other examples of sensitive and serious tones in the passage but then doesn’t completely explain them. None of the details noted refer to a particular point that supports a focused paragraph. The details don’t connect. They’re merely a string of details.

Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Quotes and Examples to Your Argument Points

Rather than merely citing phrases and lines without explanation, as the C sample does, the A response spends time thoroughly discussing the meaning of the quoted words, phrases, and sentences used to exemplify their assertions. For example, the third paragraph begins with the point that Henchard’s attempts to elevate Elizabeth in order to better integrate her into the mayor’s “lifestyle” actually do her a disservice. The student then quotes descriptive phrases that characterize Elizabeth as “considerate”, notes her successfully fulfilling her father’s expectations of her as a woman, and concludes that success leads to her failure to get them closer — to un-estrange him.

The A sample writer follows the same pattern throughout the essay: assertion, example, explanation of how the example and assertion cohere, tying both into the thesis statement. Weaving the well-chosen details into the discussion to make reasonable conclusions about what they prove is the formula for an orderly, coherent argument. The writer starts each paragraph with a topic sentence that supports the thesis statement, followed by a sentence that explains and supports the topic sentence in furtherance of the argument.

On the other hand, the B response begins the second paragraph with a general topic sentence: Hardy focuses on the differences between the daughter’s behavior and the father’s expectations. The next sentence follows up with examples of the words Elizabeth changes, leading to the broad conclusion that class difference causes clashes. They give no explanation to connect the behavior — changing her words — with how the diction reveals class differences exists. Nor does the writer explain the motivations of the characters to demonstrate the role of class distinction and expectations. The student forces the reader to make the connections.

Similarly, in the second example of the handwriting incident, the student sets out to prove Elizabeth’s independence and conformity conflict. However, the writer spends too much time re-telling the writing episode — who said what — only to vaguely conclude that 19th-century gender roles dictated the dominant and submissive roles of father and daughter, resulting in the loss of Elizabeth’s independence. The writer doesn’t make those connections between gender roles, dominance, handwriting, and lost freedom. The cause and effect of the handwriting humiliation to the loss of independence are never made.

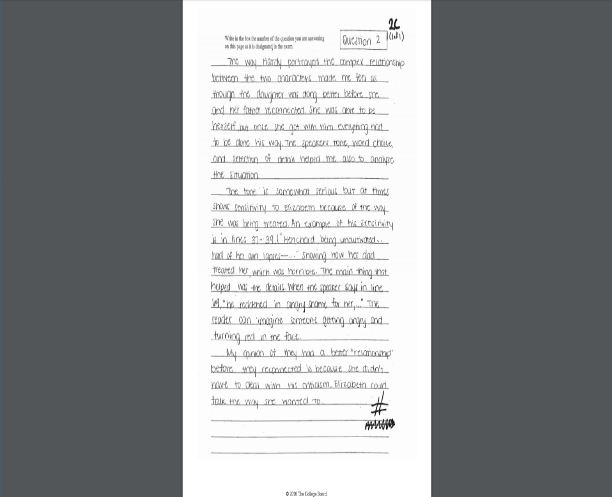

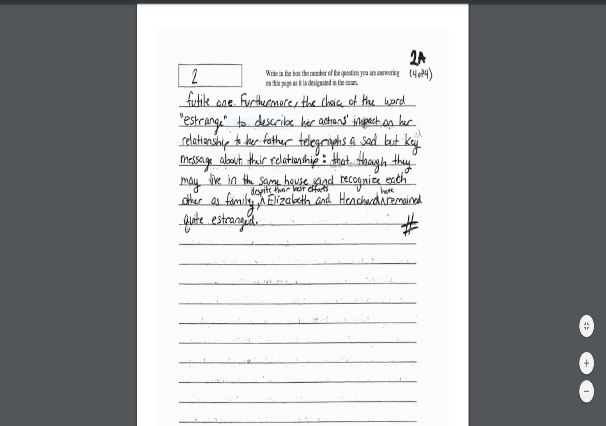

Write a Brief Conclusion

While it’s more important to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs than it is to conclude, a conclusion provides a satisfying rounding out of the essay and last opportunity to hammer home the content of the preceding paragraphs. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of the thorough preceding paragraphs, that is not as fatal to your score as not concluding or not concluding as robustly as the A essay sample.

The A response not only provides another example of the father-daughter inverse relationship — the more he helps her fit in, the more estranged they become — but also ends where the writer began: though they’re physically reunited, they’re still emotionally separated. Without repeating it verbatim, the student returns to the thesis statement at the end. This return and recap reinforce the focus and control of the argument when all of the preceding paragraphs successfully proved the thesis statement.

The B response nicely ties up the points necessary to satisfy the prompt had the writer made them clearly. The parting remarks about the inverse relationship building up and breaking down to characterize the complex relationship between father and daughter are intriguing but not well-supported by all that came before them.

Write in Complete Sentences with Proper Punctuation and Compositional Skills

Though pressed for time, it’s important to write an essay with crisp, correctly punctuated sentences and properly spelled words. Strong compositional skills create a favorable impression to the reader, like using appropriate transitions or signals (however, therefore) to tie sentences and paragraphs together, and making the relationships between sentences clear (“also” — adding information, “however” — contrasting an idea in the preceding sentence).

Starting each paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence that previews the main idea or focus of the paragraph helps you the writer and the reader keep track of each part of your argument. Each section furthers your points on the way to convincing your reader of your argument. If one point is unclear, unfocused, or grammatically unintelligible, like a house of cards, the entire argument crumbles. Excellent compositional skills help you lay it all out neatly, clearly, and fully.

For example, the A response begins the essay with “In this passage from Thomas Hardy”. The second sentence follows with “Throughout the passage” to tie the two sentences together. There’s no question that the two thoughts link by the transitional phrases that repeat and reinforce one another as well as direct the reader’s attention. The B response, however, uses transitions less frequently, confuses the names of the characters, and switches verb tenses in the essay. It’s harder to follow.

So by the time the conclusion takes the reader home, the high-scoring writer has done all of the following:

- followed the prompt

- followed the propounded thesis statement and returned to it in the end

- provided a full discussion with examples

- included quotes proving each assertion

- used clear, grammatically correct sentences

- wrote paragraphs ordered by a thesis statement

- created topic sentences for each paragraph

- ensured each topic sentence furthered the ideas presented in the thesis statement

Have a Plan and Follow it

To get a nine on the prose analysis FRQ essay in the AP® Literature and Composition exam, you should practice timed essays. Write as many practice essays as you can. Follow the same procedure each time. After reading the prompt, map out your thesis statement, paragraph topic sentences, and supporting details and quotes in the order of their presentation. Then follow your plan faithfully.

Be sure to leave time for a brief review to catch mechanical errors, missing words, or clarifications of an unclear thought. With time, an organized approach, and plenty of practice, earning a nine on the poetry analysis is manageable. Be sure to ask your teacher or consult other resources, like albert.io’s Prose Analysis practice essays, for questions and more practice opportunities.

Looking for AP® English Literature practice?

Kickstart your AP® English Literature prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Prose Examples in Literature

Prose is one of the major form of writing in different literary categories. Many written pieces depend on prose as their main structure. In contrast to poetry that depends on rhyme and meter, the prose features clear writing and natural flow.

Definition of Prose

Prose is a form of language that follows simple grammatical rules and natural speech rhythms. In contrast, the poetry is marked by fixed patterns. Prose represents the standard form of language for both writing and speaking.

It serves as a basis for numerous genres, such as short stories, novels and essays. By using complete sentences and arranging them into paragraphs, prose conveys concepts and tell stories without any restriction of formal poetic structure.

Types of Prose

Prose contains numerous forms and is categorized into many types, based on its purpose and approach. Here are the primary types of prose:

1- Narrative Prose

Narrative prose tells a story regardless of whether it is fictional or non-fictional. This category features various pieces of work, such as, novels, short stories, biographies and memoirs.

This kind of writing highlights figures in a structured scenario. For example: The classic work “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen, illustrates narrative prose by interweaving themes of love and societal evolution.

2- Descriptive Prose

This genre highlights the colorful portrayal of situations and individuals to stimulate the senses and inspire the reader’s thoughts.

It appears within narrative writing to create environment. For Example: In “Moby-Dick”, the author uses descriptive prose to explore the vastness of the sea and presents the nuances of whaling endeavors.

3- Expository Prose

Expository writing reveals knowledge and discusses matters thoroughly. It usually presents in academic works and journalistic writing.

This form of prose centers on clarity and factual evidence. For example: In the essay “Self-Reliance” by Emerson, one finds clear points made through expository prose.

4- Persuasive Prose

This sort of writing intends to inspire the readers to accept a particular view or perform a particular action. It is found speeches, essays and advertisements. For example: The speech of King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” calls for civil rights and equality.

5- Prose Poetry

Prose poetry combines concepts from prose and poetry. In this type of prose, the paragraphs are used instead of verse.

It embodies poetic traits, such as vibrant visuals and emotional intensity. For example: In “Paris Spleen” by Charles Baudelaire, it contains prose poems that analyze city life with powerful visuals and poetic expression.

Common Examples of First Prose Lines in Well-Known Novels

First lines of novels are often iconic, setting the tone for the narrative that follows. Here are a few famous examples of first prose lines:

- “Call me Ishmael.” (“Moby-Dick” by Herman Melville)

The narrator appears in this concise opening line and lays the groundwork for a grand narrative of obsession and vengeance.

- “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” (“Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen)

The line hints the core ideas of marriage and societal position in the story with a touch of irony.

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…” (“A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens)

This celebrated introductory line illustrates the paradoxes and chaos of the French Revolution and delineates the narrative’s focus on complexity.

- “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” (“Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy)

Tolstoy reveals his clear perception of human nature and the complicated dynamics of familial bonds through this opening line.

- “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” (“1984” by George Orwell)

In Orwell’s novel the first line serves as a setup for the harsh existence within.

Examples of Prose in literature

“the great gatsby” by f. scott fitzgerald.

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. ‘Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone,’ he told me, ‘just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.’ He didn’t say any more, but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that.”

The introductory passage of “The Great Gatsby” exemplifies narrative prose. Using the inner reflections of Nick Carraway, the author sets a deeply thoughtful mood in the narrative.

The prose here presents notions of status and assessment that serve to outline the novel’s investigation into wealth issues and social stratifications within the Jazz Age.

Nick’s character emerges as deliberate and insightful due to the straightforward and conversational structure of the language in the narrative.

“Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.”

In the novel, Austen sets a satirical mood through a classy prose that introduces the narrative. The elegant and removed manner of the writing playfully comments on the societal standards of Regency England focusing on the obligation for women to marry wealthy individuals.

Austen’s prose exemplifies her ability to use irony to analyze community standards in this segment. The words are clear and calculated contrasting with the hidden laughter and insights on marriage in a social agreement.

See also: Examples of Protagonist in Literature

“Moby-Dick” by Herman Melville

“Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

In the opening scene of Moby-Dick, Melville reveals the use of descriptive and philosophical prose. In rich language filled with vivid details Ishmael articulates his desperation and sense of existential hopelessness along with the atmosphere around him.

The elegant prose entertains with its elaborate structure and lengthy phrases which resonate with the narrator’s disjointed reflections while intimating broader ideas like destiny and the search for purpose.

In this passage, the language establishes the framework that the narrative will follow while examining the essence of personal psychology and existence at sea.

Difference Between Prose and Poetry

The difference between prose and poetry mostly lie in their composition and objective. Complete sentences in prose form paragraphs according to the natural rhythm of everyday conversation.

It aims to convey clarity along with extensive detail and simplicity, often seen in essays and novellas.

Poetry, on the other hand, is written in lines and stanzas and tends to employ rhyme, rhythm and meter. Through concise and figurative language, poetry seeks to convey emotions and ideas and frequently reinvents its structure to create meaningful images.

While prose seems straightforward in nature, poetry can also express ideas in a more abstract way.

See also: Elements of Play in Literature

How to Write a Prose Poem?

A prose poem blends the narrative flow of prose with the imaginative and figurative language of poetry. Here are some steps to writing a prose poem:

Choose a Theme or Emotion :

Typically prose poems concentrate on particular themes or emotions. Choose what heartfelt essence you desire to communicate.

Use Poetic Language :

Use poetic tools such as imagery and metaphors in your paragraphs. With these methods applied the prose can become a poetic work.

Write in Paragraphs :

Instead of employing traditional verse structure prose poems use a continuous paragraph. They bypass the verse pattern found in poetry and preserve the emotional richness therein.

Experiment with Rhythm and Sound :

Emphasize the structure and tone of your expression. Inspect the way the words unite and their voice when read out loud.

Be Concise and Reflective :

Prose poems regularly squeeze difficult ideas or emotions into a brief format. Concentrate on the soul of your content and study it in a quiet reflective manner.

Revise for Impact :

Rewrite your prose poem to improve clarity and emotional depth. All words must enhance the principal meaning and mood of the creation.

Prose Edda vs. Poetic Edda

The Prose Edda and Poetic Edda rank among the most significant compilations of Old Norse literature. They include key narratives and legends about Norse mythology.

Before the 13th century, Snorri Sturluson authored the Prose Edda as an instructional work on poetics and provides a narrative view of Norse mythology. This work uses simple language to convey the legends and protect them for future people.

Anonymous traditional poems make up the Poetic Edda and include tales of heroes and mythological figures. It is composed in verse and these poems reveal the elaborate poetic forms that represent their traditional oral transmission.

While the Prose Edda presents Norse mythology in a more organized and instructional way the Poetic Edda reveals it through poetic language.

See also: Literary Devices That Start With P

Similar Posts

I Have A Dream Literary Devices

Introduction to “I have dream” On a sunny day, August 28th, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. held a very…

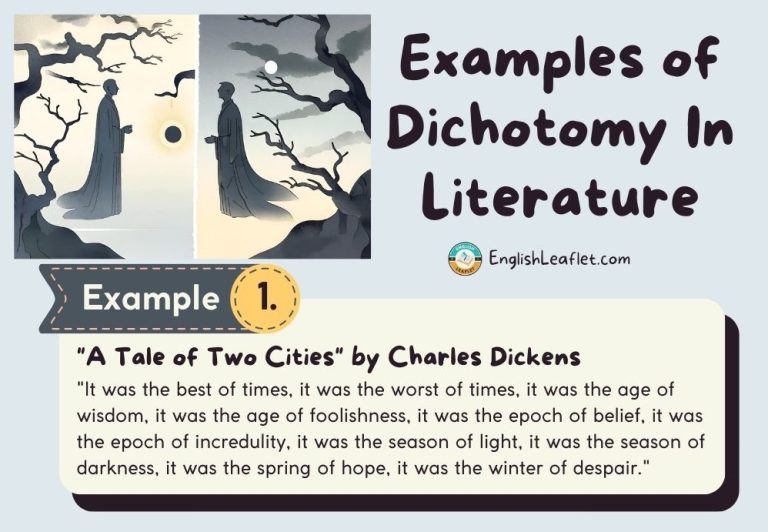

Examples of Dichotomy In Literature

Dichotomy Meaning Dichotomy is a division or contrast between the two different and opposite things. The term was originated…

Dialogue Examples in Literature | How To Write A Dialogue?

What is a Dialogue? Dialogue is a conversation between two or more people. It is featured in a book,…

Fallacy In Literature (Types & Examples)

Definition of Fallacy A fallacy means faulty logic that weakens an argument. When writers use fallacious reasoning, it hurts…

Ode In Literature (Examples & Functions)

Definition of Ode An ode is a type of lyrical poem that originated in ancient Greece and is characterized…

What is Anecdote? Types and Examples in Literature

Writers uses anecdotes to convey a message or idea to their readers. They are short stories or narratives that…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What Is Prose? Definition, Meaning, and Examples

If you’re familiar with prose , you’ve probably heard it defined as “not poetry.” In truth, its definition is more expansive. There are many types of prose; for example, prose fiction is writing that contains elements like character, setting, and theme. More broadly, prose is any writing that adheres to standard sentence and grammatical structure. In other words, prose is writing that lacks the hallmarks of poetry and song.

Turn in your paper with confidence Grammarly gives your writing extra polish Write with Grammarly

What is prose?

Prose , pronounced prōz , is defined as writing that does not follow a meter or rhyme scheme. It’s writing that follows standard grammatical rules and communicates ideas in a linear, logical order. Prose writing includes works of fiction and nonfiction .

Unless you’re a particularly prolific poet, most of the writing you do is prose. This blog post is prose. Most books are prose. Research papers are prose. In other words, prose is “regular” writing—the kind of writing that isn’t constrained by stanzas, meter, rhyme, or any other stylistic formatting. Its purposes vary and include entertaining the reader as well as informing and persuading them. Its style serves all of these purposes by relying on familiar language structures to communicate directly with the reader.

Prose is a mass noun , which means it does not have a plural form. As it’s a mass noun, you wouldn’t discuss prose as a singular piece of writing or as multiple pieces—when discussing a singular prose work, you would refer to the specific type of work, such as “a book” or “an article . ” Similarly, to discuss multiple works of prose, you would say something like “the collection of prose” to refer to a library of books or an anthology of prose writing.

4 types of prose

As we mentioned earlier, prose includes both fictional and nonfictional writing. There are four defined types of prose. They are:

1 Fictional prose

As its name implies, prose fiction is prose that tells a story. Examples include:

- Short stories

- Flash fiction

Fictional prose contains the five features of fiction: mood, point of view, character, setting, and plot.

2 Nonfictional prose

Nonfictional prose is prose that tells a true story or otherwise communicates factual information. Guidebooks, memoirs, analytical essays , editorials, news stories, and textbooks are all examples of nonfictional prose. The language used in nonfictional prose can vary widely, from the formal language of academic papers to the more subjective writing found in opinion pieces. The uniting characteristic of nonfictional prose is that these pieces of writing do not tell fictional stories.

3 Heroic prose

Heroic prose is similar to fictional prose but has one crucial difference: Traditionally, it’s not written down. Instead, these stories are passed from generation to generation through oral tradition. This is often reflected in the story’s use of language, which is particularly suited to recitation.

A few examples of heroic prose include:

- The thirteenth-century Icelandic sagas Vǫlsunga saga and Thidriks saga

- The Fenian cycle, a collection of Irish tales recorded in the twelfth century telling the story of hero Finn McCool

4 Prose poetry

Although poetry usually lives outside the constraints of prose, some poems use prose language. The prose poem “ [Kills bugs dead.],” by Harryette Mullen, is a good example:

Kills bugs dead. Redundancy is syntactical overkill. A pin-prick of peace at the end of the tunnel of a nightmare night in a roach motel. Their noise infects the dream. In black kitchens they foul the food, walk on our bodies as we sleep over oceans of pirate flags. Skull and crossbones, they crunch like candy. When we die they will eat us, unless we kill them first. Invest in better mousetraps. Take no prisoners on board ship, to rock the boat, to violate our beds with pestilence. We dream the dream of extirpation. Wipe out a species, with God at our side. Annihilate the insects. Sterilize the filthy vermin.

Although this poem is certainly stylized and uses figurative language, it uses prose sentence structure. The use of prose language makes it a prose poem.

How do you write prose?

When you’re writing prose, stick to standard grammatical rules and structures. Deviate from these rules only when doing so will immerse the reader further into the text or help them understand it better, such as when writing:

Follow natural speech patterns to help the reader understand your message, which is your goal with these types of writing.

Beyond these guidelines, follow the rules for the specific type of writing you’re doing. For example, if you’re writing a research paper or another kind of academic work, use academic language and format your writing according to the appropriate style guide. Similarly, format personal essays, articles, emails, and any other prose writing you do according to the generally accepted format for that type of writing.

Although prose may contain literary devices, such devices should not make up the bulk of the text. Rather, incorporate literary devices as a way to enhance the more linear text in your prose writing.

Prose vs. poetry

To understand the differences between prose and poetry, think about the things that make poetry unique:

- Deliberate line breaks

- Traditional poetic structures, like a sonnet or a ballad

- Rhyme scheme

- Metrical structure

- Significant use of figurative language and other literary devices

- Formatting that stands out visually on the page

Keep in mind that not every poem checks all of these boxes. Plenty of poems don’t rhyme, and not every poem fits a set metrical structure; in addition, as you saw in the prose poetry example above, a poem doesn’t necessarily have to contain line breaks or stylized formatting. However, when a piece of writing uses one or more of these elements to primarily communicate a theme or mood, rather than convey information, it’s generally considered a poem.

In contrast, prose:

- Primarily uses literal, everyday language

- Contains sentences that continue across lines

- Is formatted into paragraphs, lines, and lists

- Generally follows natural speech patterns

Prose examples

- To learn more, please visit our website.

- Crocodiles are the largest reptiles in the world. They coexisted with dinosaurs, making them one of the oldest living species today.

- After we stopped for gasoline, we had a renewed sense of purpose for the road trip.

- Thank you very much for your inquiry. Due to the volume of emails we receive, we cannot respond to each individually.

- “Yes, I would love to help you build a shed!” he exclaimed.

- There are seven continents on Earth.

The prose is writing that uses standard grammatical rules and structure. Prose writing is organized into sentences and paragraphs and generally communicates ideas in a linear narrative.

What are the types of prose?

- Fictional prose

- Nonfictional prose

- Heroic prose

- Prose poetry

What’s the difference between poetry and prose?

While poetry is characterized by having meter, rhyme schemes, stanzas, and other stylistic formatting, prose is characterized by the lack of these.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Prose

I. What is a Prose?

Prose is just non-verse writing. Pretty much anything other than poetry counts as prose: this article, that textbook in your backpack, the U.S. Constitution, Harry Potter – it’s all prose. The basic defining feature of prose is its lack of line breaks:

In verse, the line ends

when the writer wants it to, but in prose

you just write until you run out of room and then start a new line.

Unlike most other literary devices , prose has a negative definition : in other words, it’s defined by what it isn’t rather than by what it is . (It isn’t verse.) As a result, we have to look pretty closely at verse in order to understand what prose is.

II. Types of Prose

Prose usually appears in one of these three forms.

You’re probably familiar with essays . An essay makes some kind of argument about a specific question or topic. Essays are written in prose because it’s what modern readers are accustomed to.

b. Novels/short stories

When you set out to tell a story in prose, it’s called a novel or short story (depending on length). Stories can also be told through verse, but it’s less common nowadays. Books like Harry Potter and the Fault in Our Stars are written in prose.

c. Nonfiction books

If it’s true, it’s nonfiction. Essays are a kind of nonfiction, but not the only kind. Sometimes, a nonfiction book is just written for entertainment (e.g. David Sedaris’s nonfiction comedy books), or to inform (e.g. a textbook), but not to argue. Again, there’s plenty of nonfiction verse, too, but most nonfiction is written in prose.

III. Examples of Prose

The Bible is usually printed in prose form, unlike the Islamic Qur’an, which is printed in verse. This difference suggests one of the differences between the two ancient cultures that produced these texts: the classical Arabs who first wrote down the Qur’an were a community of poets, and their literature was much more focused on verse than on stories. The ancient Hebrews, by contrast, were more a community of storytellers than poets, so their holy book was written in a more narrative prose form.

Although poetry is almost always written in verse, there is such a thing as “prose poetry.” Prose poetry lacks line breaks, but still has the rhythms of verse poetry and focuses on the sound of the words as well as their meaning. It’s the same as other kinds of poetry except for its lack of line breaks.

IV. The Importance of Prose

Prose is ever-present in our lives, and we pretty much always take it for granted. It seems like the most obvious, natural way to write. But if you stop and think, it’s not totally obvious. After all, people often speak in short phrases with pauses in between – more like lines of poetry than the long, unbroken lines of prose. It’s also easier to read verse, since it’s easier for the eye to follow a short line than a long, unbroken one.

For all of these reasons, it might seem like verse is actually a more natural way of writing! And indeed, we know from archaeological digs that early cultures usually wrote in verse rather than prose. The dominance of prose is a relatively modern trend.

So why do we moderns prefer prose? The answer is probably just that it’s more efficient! Without line breaks, you can fill the entire page with words, meaning it takes less paper to write the same number of words. Before the industrial revolution, paper was very expensive, and early writers may have given up on poetry because it was cheaper to write prose.

V. Examples of Prose in Literature