An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Socioeconomic Status and Quality of Life: An Assessment of the Mediating Effect of Social Capital

Jonathan aseye nutakor, ebenezer larnyo, stephen addai-danso, debashree tripura.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected]

Received 2023 Jan 9; Revised 2023 Feb 27; Accepted 2023 Feb 27; Collection date 2023 Mar.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Socioeconomic status has been found to be a significant predictor of quality of life, with individuals of higher socioeconomic status reporting better quality of life. However, social capital may play a mediating role in this relationship. This study highlights the need for further research on the role of social capital in the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life, and the potential implications for policies aimed at reducing health and social inequalities. The study used a cross-sectional design with 1792 adults 18 and older from Wave 2 of the Study of Global AGEing and Adult Health. We employed a mediation analysis to investigate the relationship between socioeconomic status, social capital, and quality of life. The results showed that socioeconomic status was a strong predictor of social capital and quality of life. In addition to this, there was a positive correlation between social capital and quality of life. We found social capital to be a significant mechanism by which adults’ socioeconomic status influences their quality of life. It is crucial to invest in social infrastructure, encourage social cohesiveness, and decrease social inequities due to the significance of social capital in the connection between socioeconomic status and quality of life. To improve quality of life, policymakers and practitioners might concentrate on creating and fostering social networks and connections in communities, encouraging social capital among people, and ensuring fair access to resources and opportunities.

Keywords: socioeconomic status, social capital, quality of life, EUROHIS-QOL

1. Introduction

Extensive research has shed light on the relationship between one’s socioeconomic status and their level of health and overall quality of life [ 1 ]. In addition, research conducted over the course of the past two decades has uncovered a correlation between social capital and quality of life [ 2 , 3 ]. In recent years, efforts to identify and address the social determinants of people’s health and quality of life have led to widespread acknowledgment of certain elements of social capital as complements to public health measures [ 4 , 5 ].

Social capital remains a highly effective idea that has been thought about from a range of viewpoints, yet a number of its qualities have been utilized in public health research. The ability of actors, be they individuals or groups, to obtain benefits by virtue of their participation in social networks and other social structures is one definition of social capital [ 2 ]. Whereas Coleman, Bourdieu, and Putnam defined social capital from different viewpoints [ 6 , 7 , 8 ], they all acknowledged it as a significant social asset and as individual and group characteristics that can be quantified and assessed within a social network for health and wellbeing advantages. This study defines social capital as a useful social resource that adults can use at the individual and community levels to improve their health and quality of life. These resources can come from families, schools, colleagues, and community members. They can be acquired to get the most health benefits and possibly protect the quality of life of adults from the impacts of socioeconomic inequality [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Some individuals have the ability to leverage the pre-existing resources of their family or their participation in influential groups or associations to their benefit. Social capital is a collective asset that is advantageous to everyone who is a part of a social structure [ 12 ]. It is an asset not only for wealthy and privileged people, but also for those who are less privileged [ 13 ]. Social capital is built, maintained, and sustained with the help of trust, cooperation, and reciprocity [ 14 ]. Social capital is a health determinant because social ties and interactions may provide information and real support. The way in which a society’s social structure, as well as its ideas of familial relationships and social connections, develops throughout the course of time is directly related to the way in which social capital changes over time [ 15 , 16 ]. As a result, certain efforts have been made to build social capital because it can be beneficial in improving people’s health, presumably regardless of their wealth status [ 13 ].

The concept of social capital appears to incorporate aspects of both psychosocial factors and social wellbeing. This is due to the fact that it serves as an essential channel through which an adult’s social environment can influence the majority of the factors that comprise their quality of life [ 9 , 17 ]. However, social inequality in adults’ quality of life is frequently quantified by looking at differences in adults’ financial status, while social capital is largely ignored as a measurement tool. This is despite the fact that social capital is one of the most important factors in adulthood. It has been discovered that one’s socioeconomic situation has an effect on their health and quality of life both directly [ 9 , 10 , 17 , 18 , 19 ] and indirectly through psychosocial factors such as the failure of the poor to form ties and networks for their own advantage [ 8 , 9 , 17 ]. However, these psychosocial characteristics have the potential to operate as protective mechanisms, which can help mitigate some of the negative consequences that socioeconomic status disparities have on quality of life. This is due to the fact that research has shown that a person’s socioemotional and psychosocial resources, which they build up via their relationships with others in their social environment, can attenuate the negative impacts of their socioeconomic status on their quality of life [ 9 , 10 , 17 ]. This supports the idea that social capital may serve as a buffer against health problems, particularly for those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

In addition, social capital is widely recognized as a key determinant of quality of life because it can provide individuals with important support and resources that enhance their well-being. Quality of life is an essential indicator of human health that is influenced by physical, mental, and social factors [ 20 ]. Quality of life has to do with how satisfied or happy a person is, which is affected by health. It is a key indicator of both physical and mental health. Negative social capital, on the other hand, can have detrimental consequences on the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life, especially in the setting of in-group violence and gang activities. Negative social capital can contribute to the propagation of negative stereotypes and stigmatization of specific groups, resulting in their further marginalization and exclusion from society. In addition, it can destroy social trust, resulting in feelings of isolation and separation.

Recognizing the protective roles of social capital can help address the differences in quality of life between adults based on their socioeconomic status. This is especially important in low–and middle–income countries, where many adults face risks related to poverty and low socioeconomic status. On the other hand, there is a dearth of empirical evidence about the protective function of social capital using a nationally representative sample of adults in Ghana and most low-and middle-income economies. As a result, the purpose of this study is to investigate the potential for social capital to mediate the relationship between an adult’s socioeconomic status and their quality of life using nationally representative data from a low-and middle-income country [Ghana]. In light of the foregoing, we employed a mediation analysis to examine the interplay between socioeconomic status, social capital, and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilized data from SAGE Wave 2 of the World Health Organization’s Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health. SAGE was carried out in six low- and middle-income countries (China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russian Federation, and South Africa). There are 4 waves in WHO SAGE, 0, 1, 2 and 3. This study focused on wave 2 because wave 3 is yet to be made available to the public. The data collected in Ghana was utilized for this study. This study’s total sample size was 1792 respondents. This group consisted of adults older than 18 years. In order to accommodate respondents in Ghana who lacked English language skills, the questionnaire used for this research was translated into a variety of the country’s native tongues. The WHO Ethical Review Committee (RPC146) and the University of Ghana Medical School Ethics and Protocol Review Committee approved SAGE [Accra, Ghana] [ 21 ].

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. socioeconomic status.

Socioeconomic status was defined using a combination of education and household income. Five groups were made based on the level of education of the respondents. These included individuals who have completed less than primary school, primary school, secondary school, high school, and a university/college/postgraduate degree [ 22 ]. Likewise, household income was categorized into five groups. These ranged from the lowest to the highest income brackets [ 23 ]. We combined the two variables to create an overall socioeconomic status score. The total socioeconomic status score ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher socioeconomic status.

2.1.2. Quality of Life

The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index was utilized in order to do the analysis for quality of life [ 24 ]; this index is the condensed version of the Quality-of-Life Instrument that was developed by the World Health Organization. In addition, the EUROHIS-QOL 8-item measure has been shown to have validity and reliability that are satisfactory [ 25 ]. The questions used to assess quality of life were, (1) Do you have enough energy for everyday life?, (2) Do you have enough money to meet your needs?, (3) How satisfied are you with your health?, (4) How satisfied are you with yourself?, (5) How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily living activities?, (6) How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?, (7) How satisfied are you with the conditions of your living place?, and (8) How would you rate your overall quality of life? The total score for these eight questions was between 8 and 40, where 8 was the lowest possible score, and 40 was the highest. Respondents who were unsatisfied with all areas of their quality of life received the lowest possible score, while those who were extremely satisfied with all aspects of their wellbeing received the highest possible score.

2.1.3. Social Capital

In order to assess social capital, two different variables were constructed. These included social participation and trust. The determinants of social capital were derived from a combination of fourteen separate questions. In order to determine whether or not the respondents had a trusting relationship with the individuals [friends, neighbors, and family] in their immediate environment, questions pertaining to trust were posed to them. In addition, questions on social participation focused on the participants’ involvement with family, friends, neighbors, and public gatherings. Assessing social capital is a key method for assessing the extent of social cohesiveness and collective activity in a society. Trust and social participation are important indicators of social capital in terms of its role as a mediator between socioeconomic status and quality of life [ 26 ]. Social capital may promote the wellbeing of individuals through enhancing social interaction, resource access, and resource utilization. The operationalization of social capital does not follow a one-size-fits-all model, and various studies may utilize different measures based on their study objective and environment. Furthermore, social capital may be measured at several levels, including the individual, community, and societal levels.

2.1.4. Sociodemographic

There were male and female codes for gender. Age was coded and classified into seven distinct groups. These age groups ranged from 18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 and older. The categories of urban and rural were assigned based on the resident’s location. There were five distinct categories of people based on their marital status. They included those who have never been married, those who are currently married, those who cohabit, those who are separated or divorced, and those who have lost a spouse.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

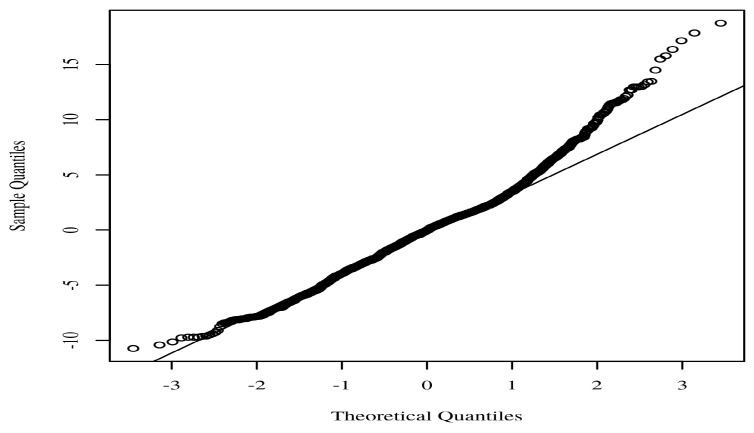

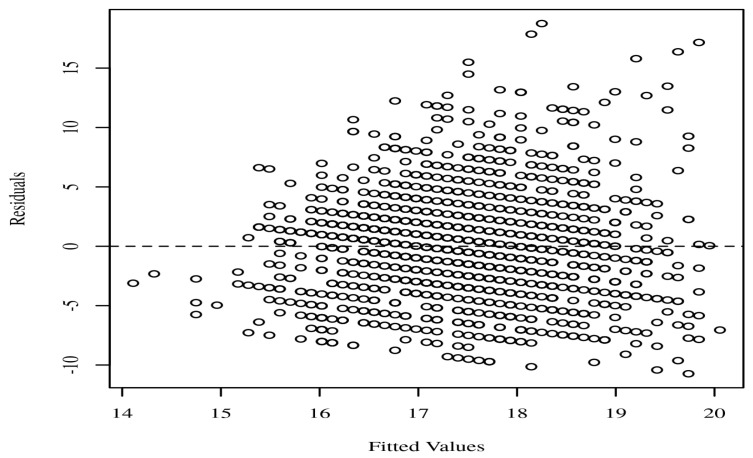

Analyses of the data were performed using STATA SE 14.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) and Intellectus Statistics. The following categories of summary statistics were calculated: gender, age, residence, marital status, education level, and income quintile. A causal mediation study was carried out to determine if social capital mediated the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life. The mediation model was based on an exposure variable, mediator, and an outcome variable. In order to test the normality assumption, the quantiles of the model residuals were plotted against the quantiles of a Chi-square distribution. This allowed for an accurate evaluation of the assumption. The homoscedasticity of the data was determined by making a scatter plot of the residuals vs. the anticipated values. The occurrence of multicollinearity between predictors was investigated through the use of variance inflation factors (VIFs), which were computed. When p was less than 0.05, the results of the study were regarded as significant.

The total sample size for this study was 1792 respondents. It was found that females made up 50.33 percent of the total respondents. The group of adults aged 55 to 64 made up the largest portion of the sample (26.45%). When it came to the respondents’ places of residence, those who lived in rural areas made up the majority of the group (51.95%). The marital status of the respondents was assessed as part of the study. According to the data, the group of respondents who are currently married made up 57.09 percent of the total. In terms of the respondents’ educational backgrounds, the largest group was comprised of those who had completed secondary school (26.34%). Finally, we divided the respondents’ household income into five categories and evaluated the results. According to the findings of our survey, the majority of respondents, or 38.62 percent, were positioned in the lowest quintile. The summary statistics can be found in Table 1 .

Summary Statistics Table for Interval and Ratio Variables.

n = Sample size; % = Percent.

It is essential that the quantiles of the residuals do not significantly depart from the theoretical quantiles for the assumption of normality to be validated. The reliability of the parameter estimates may be called into question if there is a significant deviation. A Q-Q scatterplot of the model residuals is shown in Figure 1 . If the points seem to be randomly distributed, have a mean of zero, and there is no visible curvature, then the assumption of homoscedasticity has been satisfied. A scatterplot of the anticipated values and the model residuals can be seen in Figure 2 . In the regression model, each of the predictors has a VIF that is less than 10. The VIF for each predictor included in the model is detailed in Table 2 .

Regression model Q-Q scatterplot for residual normality.

Residuals scatterplot testing homoscedasticity.

Variance Inflation Factors for Socioeconomic status and social capital.

VIF—Variance Inflation Factor.

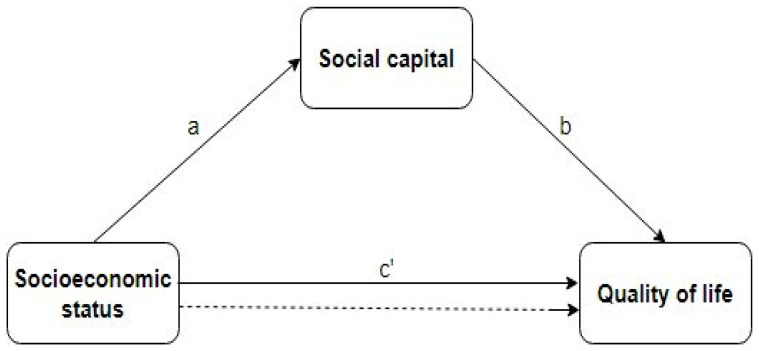

Using bootstrapping (N = 100) and confidence intervals based on percentiles, the mediating effects were investigated based on the indirect and direct effects. The outcomes were determined using an alpha of 0.05. Figure 3 displays a diagram of the mediation model.

Node diagram for the mediation analysis. The dotted line represents the effect of socioeconomic status on quality of life, when social capital is not taken into account as a mediator. The paths a, b and c’ are direct effects.

As shown in Table 3 , there is a positive relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life. The direct effect on average was significant, with a value of B = 0.21, 95% CI [0.14, 0.34], p < 0.021. This shows that socioeconomic status is a strong predictor of life quality. In Table 4 , a similar association was found between social capital and quality of life. Thus, the direct effect of social capital on quality of life was significant, with a value of B = 1.49, 95% CI [1.11, 1.56], p < 0.001. In Table 5 , a positive relationship was observed between socioeconomic status and social capital B = 0.06, 95% CI [0.03, 0.08]. Through social capital, the average indirect effect of socioeconomic status on quality of life was significant ( B = 0.09, 95% CI [0.03, 0.15]) ( Table 6 ). In other words, the effect of socioeconomic status on quality of life was mediated by social capital.

Direct effect of socioeconomic status on Quality of life.

* p < 0.05; B —Unstandardized Beta; SE —Standard Error; CI—Confidence Interval; t — t -Test Statistic.

Direct effect of social capital on Quality of life.

*** p < 0.001; B —Unstandardized Beta; SE —Standard Error; CI—Confidence Interval; M—Mean.

Direct effect of socioeconomic status on Social capital.

*** p < 0.001; B —Unstandardized Beta; SE —Standard Error; CI—Confidence Interval; t — t -Test Statistic.

Indirect effect of Socioeconomic status on Quality of life through Social capital.

4. Discussion

Consistent with the World Health Organization’s Social Determinants of Health framework, we discovered evidence that social capital mediates the effect of socioeconomic status on quality of life [ 27 ]. This finding is also consistent with a systematic review that was conducted in 2013 and came to the conclusion that social capital might be able to buffer the adverse impacts of poor socioeconomic status on one’s health [ 28 ]. The World Health Organization’s Social Determinants of Health framework recognizes that social factors such as social capital, socioeconomic status, and other social determinants, have a significant impact on health outcomes and quality of life [ 29 ]. According to a research conducted in Canada, social capital mediates the relationship between education and self-rated health [ 30 ]. In the United Kingdom, a study showed that social capital mediated the relationship between income and self-rated health [ 31 ]. Other research showed opposite findings to our own. In the United States, a study showed that social capital did not mediate the association between socioeconomic status and self-rated health [ 32 ]. Also, a similar study showed that social capital did not mediate the association between socioeconomic status and health-related quality of life [ 33 ]. Overall, these findings imply that social capital may not always serve as a mediator between socioeconomic status and quality of life and that other factors may be at play. The relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life is complex and multifaceted.

The mediation of the influence of socioeconomic status on quality of life by social capital in this setting shows that social capital plays a crucial role in the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life. This study shows that persons with greater levels of social capital are better equipped to harness the benefits associated with a higher socioeconomic status in order to obtain a higher quality of life. Social capital may give access to resources and opportunities that are unavailable to others without such connections, and it can contribute to the development of an essential sense of social support and belonging [ 12 ]. In addition, the fact that social capital mediates the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life shows that social capital might mitigate the detrimental impacts of social and economic disadvantage on health and well-being [ 28 ]. This is a significant finding, since it shows that interventions focused at developing and sustaining social capital may have the potential to enhance health outcomes and minimize health inequalities across people and groups. Overall, the findings that social capital mediates the influence of socioeconomic status on quality of life supports a growing corpus of research on social determinants of health and emphasizes the significance of strong social ties and relationships to increase well-being [ 28 ]. The results of this study also show that health systems need to do more than just provide preventive and curative care. They also need to put money into programs that help people with low incomes build or keep social capital. These programs may include community development programs, mentoring programs, skill-building programs, and support groups. These programs focus on building community connections, providing opportunities for skill-building and support, and creating a sense of belonging and empowerment.

According to our study, socioeconomic status and quality of life are positively correlated. Another study with similar results supports this [ 34 ]. Research have repeatedly demonstrated that socioeconomic status has a strong direct impact on quality of life [ 5 , 13 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Comparatively to individuals with lower socioeconomic status, those with higher socioeconomic status typically enjoy higher quality of life [ 37 ]. This is because having a higher socioeconomic standing frequently translates into having access to better healthcare, employment prospects, and educational institutions, as well as more income and wealth [ 38 ]. More stable living conditions, such as having access to a clean and safe place to live, reliable transportation, and other basic necessities are also related to higher socioeconomic status [ 39 ]. All of these elements may lead to improved physical and mental health outcomes, more sociable engagement and community involvement, and higher levels of personal contentment. Although socioeconomic status may have a big influence on quality of life, the relationship between the two is complex and multifaceted. An individual’s opinion of their quality of life may also be influenced by other elements including personal values, cultural background, and life events.

In a similar vein, a positive correlation was found to exist between a person’s socioeconomic status and their social capital. A positive association between socioeconomic status and social capital indicates that when a person’s socioeconomic standing rises, so does their social capital. Higher social capital has been shown to correlate positively with higher socioeconomic status in recent research [ 5 , 13 , 40 ]. This association makes logical sense, since individuals with a better socioeconomic standing often have more resources and chances to establish and maintain social connections. They may have access to better schools, employment opportunities, and other social and cultural organizations, which can facilitate the formation and maintenance of important social bonds [ 41 ]. In exchange, these social relationships can give the individual extra resources and possibilities, such as information access, employment leads, and other types of assistance. Overall, the positive correlation between socioeconomic status and social capital suggests that individuals with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to have a broader and more diverse network of social connections, which can provide them with significant advantages in a variety of aspects of their lives. Again, we found a positive relationship between social capital and quality of life, which is consistent with previous research that found a lack of social contact is strongly associated with low quality of life [ 40 ]. A positive correlation between social capital and quality of life indicates that as social capital improves, so does people’ quality of life. This association makes sense since social capital may provide individuals with a variety of resources and possibilities, including social support, access to knowledge and resources, and social and economic development prospects [ 28 ]. These resources can contribute to a greater quality of life by enhancing health, fostering social connections and a feeling of belonging, and offering access to resources and opportunities that may not be available to persons without these connections. In addition, social capital can facilitate the development of trust and collaboration between individuals, resulting in more stable and resilient societies [ 42 ].

This study adds to the existing literature by showing that social capital mediates the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life [ 9 , 10 , 43 , 44 ]; yet, it is still an original finding with significant implications. Despite the fact that earlier studies have shown that both socioeconomic status and social capital are important in determining health outcomes, this study provides evidence that social capital plays a crucial role in relating socioeconomic status to quality of life. In other words, it emphasizes the importance of interpersonal interactions in achieving the benefits associated with a greater socioeconomic status. This conclusion is especially significant because it shows that initiatives designed to improve health outcomes should prioritize the development and maintenance of networks of social support rather than merely increasing access to financial resources or encouraging healthier individual behaviors. This is a departure from the standard public health practice, which has concentrated on treatments at the individual level, and an advancement toward one that takes into account the impact of social determinants of health. In addition, the focus of this study on social capital as a mediator of the association between socioeconomic status and quality of life is a unique contribution to the field. Policymakers and practitioners may need to concentrate on lowering inequalities in social capital to reduce inequalities in quality of life. Efforts to improve educational and economic prospects for those with a low socioeconomic status, for instance, may raise their social capital and, in turn, their quality of life.

The findings of this study have implications for future research which can also be utilized in the formation of national policies and programs that are geared toward the general population. More study is required to understand the mechanisms through which social capital functions as a mediator, as well as the variables that impact the development and distribution of social capital. In addition, research might investigate the efficacy of certain treatments targeted to improve social capital among persons of low socioeconomic status. Health professionals and policymakers both have a responsibility to see that older adults receive the best possible care, both for their physical and functional needs and for their emotional and psychological well-being. This includes helping them feel more useful, which has been linked to better physical functioning [ 45 ], by getting them more involved in their communities and letting them help make decisions at home.

Several theoretical approaches can be drawn from the finding that social capital influences the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life. First, it supports the social capital theory, which suggests that social connections, networks, and norms are valuable resources that can help people and communities do better [ 46 ]. The study implies that social capital can provide those with lower socioeconomic status with access to resources and assistance that enhance their quality of life. Second, the study emphasizes the significance of social factors in understanding health inequalities. It shows that treatments that promote social capital may be an effective means of reducing disparities in the quality of life between people of various socioeconomic backgrounds. Lastly, the study emphasizes the importance of policies that promote the growth of social capital. For instance, policies that stimulate social involvement, promote community development, and support the establishment of social networks may be crucial for enhancing the quality of life for those with a lower socioeconomic status.

The strength of this study lies in the fact that it is one of the few that analyze the relationship between socioeconomic status, social capital, and quality of life using a nationally representative sample of adults from a low- and middle-income country. There are some limitations to this study. Because this was a cross-sectional study, we are unable to determine whether socioeconomic status or social capital has a causal effect on quality of life. However, the proposed mediation model is in line with the WHO’s Social Determinants of Health Framework, providing evidence for the potential causal impacts of socioeconomic status and social capital on quality of life. Cross-sectional studies are not designed to provide causal inferences because all data are collected at a single point in time. On the basis of the results of a cross-sectional research study alone, it is not possible to tell whether socioeconomic status or social capital has a causal influence on quality of life. The Social Determinants of Health framework acknowledges that social and economic factors, such as socioeconomic status and social capital, may have a substantial influence on an individual’s health and well-being. To prove causality, future research would require longitudinal or experimental designs to determine their impacts on quality of life over time. Nonetheless, the current study provides a solid foundation for future research in this area and underlines the potential significance of social capital in enhancing health and well-being. In addition, the majority of the responses to the questions were self-reported, which means that there is a possibility of recollection bias and that the results encounter reliability issues. Finally, the sample’s sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics are very varied. This may be observed in the size disparity between individuals who attended university and those who did not. It’s possible that the socioeconomic status of the university’s subjects is higher than that of the non-graduates.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study have substantial implications for public health policy and practice because they imply that interventions focused at boosting social capital might assist to minimize health inequalities and improve health outcomes, especially among disadvantaged groups. The findings of the study underscore the need for more research into the particular processes through which social capital improves health outcomes, as well as the long-term benefits of social capital interventions on health outcomes. It is crucial to emphasize that this is a cross-sectional research study, therefore it cannot show a causal relationship. Yet, the results of this study provide a solid framework for future research and emphasize the potential significance of social capital in enhancing health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to DataFirst for having allowed us access to the data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and J.A.N.; Formal analysis, J.A.N. and E.L.; Investigation, D.T.; Methodology, L.Z. and J.A.N.; Software, J.A.N. and E.L.; Supervision, L.Z.; Validation, J.A.N.; Visualization, E.L.; Writing—original draft, J.A.N.; Writing—review & editing, S.A.-D. and D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town Commerce (REC 2020/04/017) and reciprocal ethics from Stellenbosch University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/NIDS-CRAM (accessed on 6 December 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no financial support or relationships that may pose conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Research on the Construction and Supporting Strategy of Value-Oriented Payment Model for Outpatient Care of Chronic Diseases (National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 71974064.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

- 1. Larnyo E., Dai B., Nutakor J.A., Ampon-Wireko S., Larnyo A., Appiah R. Examining the impact of socioeconomic status, demographic characteristics, lifestyle and other risk factors on adults’ cognitive functioning in developing countries: An analysis of five selected WHO SAGE Wave 1 Countries. Int. J. Equity Health. 2022;21:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01622-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Christian A.K., Sanuade O.A., Okyere M.A., Adjaye-Gbewonyo K. Social capital is associated with improved subjective well-being of older adults with chronic non-communicable disease in six low-and middle-income countries. Glob. Health. 2020;16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0538-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Baum F. The New Public Health/Fran Baum. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Bwalya J.C., Sukumar P. The Relationship between Social Capital and Children’s Health Behaviour in Ireland. 2019. [(accessed on 12 March 2022)]. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3418320 .

- 5. Addae E.A. The mediating role of social capital in the relationship between socioeconomic status and adolescent wellbeing: Evidence from Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:20. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8142-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Putnam R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster; New York, NY, USA: 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Bourdieu P., Richardson J.G. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Forms Cap. 1986;241:258. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Coleman J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988;94:S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Buijs T., Maes L., Salonna F., Van Damme J., Hublet A., Kebza V., Costongs C., Currie C., De Clercq B. The role of community social capital in the relationship between socioeconomic status and adolescent life satisfaction: Mediating or moderating? Evidence from Czech data. Int. J. Equity Health. 2016;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0490-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Moore G.F., Littlecott H.J., Evans R., Murphy S., Hewitt G., Fletcher A. School composition, school culture and socioeconomic inequalities in young people’s health: Multi-level analysis of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Wales. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2017;43:310–329. doi: 10.1002/berj.3265. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Novak D., Emeljanovas A., Mieziene B., Štefan L., Kawachi I. How different contexts of social capital are associated with self-rated health among Lithuanian high-school students. Glob. Health Action. 2018;11:1477470. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1477470. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Alecu A., Helland H., Hjellbrekke J., Jarness V. Who you know: The classed structure of social capital. Br. J. Sociol. 2022;73:505–535. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12945. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Kaur M., Chakrapani V., Newtonraj A., Lakshmi P.V.M., Vijin P.P. Social capital as a mediator of the influence of socioeconomic position on health: Findings from a population-based cross-sectional study in Chandigarh, India. Indian J. Public Health. 2018;62:294. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_274_17. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Cruz-Torres C.E., Martín Del Campo-Ríos J. Social capital in Mexico moderates the relationship of uncertainty and cooperation during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic. J. Community Psychol. 2022;50:1048–1059. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22699. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Putnam R.D. Who Killed Civic America. 1996. [(accessed on 28 June 2022)]. Available online: https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/whokilledcivicamerica .

- 16. Coleman J.S. Foundations of Social Theory. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Ge T. Effect of socioeconomic status on children’s psychological well-being in China: The mediating role of family social capital. J. Health Psychol. 2020;25:1118–1127. doi: 10.1177/1359105317750462. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Inchley J., Currie D. Growing Up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-Being. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2016. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from the 2013/2014 Survey. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Xu F., Cui W., Xing T., Parkinson M. Family socioeconomic status and adolescent depressive symptoms in a Chinese low–and middle–income sample: The indirect effects of maternal care and adolescent sense of coherence. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:819. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00819. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. The WHOQOL Group Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Nutakor J.A., Dai B., Gavu A.K., Antwi O.-A. Relationship between chronic diseases and sleep duration among older adults in Ghana. Qual. Life Res. 2020;29:2101–2110. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02450-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Nutakor J.A., Dai B., Zhou J., Larnyo E., Gavu A.K., Asare M.K. Association between socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning among older adults in Ghana. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2021;36:756–765. doi: 10.1002/gps.5475. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Dai B., Nutakor J.A., Zhou J., Larnyo E., Asare M.K., Danso N.A.A. Association between socioeconomic status and physical functioning among older adults in Ghana. J. Public Health. 2022;30:1411–1420. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01471-0. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Luo M., Ding D., Bauman A., Negin J., Phongsavan P. Social engagement pattern, health behaviors and subjective well-being of older adults: An international perspective using WHO-SAGE survey data. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:99. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7841-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Da Rocha N.S., Power M.J., Bushnell D.M., Fleck M.P. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: Comparative psychometric properties to its parent WHOQOL-BREF. Value Health J. Int. Soc Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2012;15:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.035. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Kawachi I., Kennedy B.P., Lochner K., Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87:1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1491. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. World Helath Organization A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. 2010. [(accessed on 12 June 2022)]. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44489 .

- 28. Uphoff E.P., Pickett K.E., Cabieses B., Small N., Wright J. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: A contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int. J. Equity Health. 2013;12:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-54. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Braveman P., Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129((Suppl. S2)):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Carpiano R.M. Toward a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help? Soc. Sci Med. 2006;62:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.020. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Snelgrove J.W., Pikhart H., Stafford M. A multilevel analysis of social capital and self-rated health: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;68:1993–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Kim D., Subramanian S.V., Kawachi I. Social Capital and Health. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2008. Social capital and physical health: A systematic review of the literature; pp. 139–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Ladin K., Wang R., Fleishman A., Boger M., Rodrigue J.R. Does social capital explain community-level differences in organ donor designation? Milbank Q. 2015;93:609–641. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12139. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Yang Y., Wang S., Chen L., Luo M., Xue L., Cui D., Mao Z. Socioeconomic status, social capital, health risk behaviors, and health-related quality of life among Chinese older adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2020;18:291. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01540-8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Gao B., Yang S., Liu X., Ren X., Liu D., Li N. Association between social capital and quality of life among urban residents in less developed cities of western China: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2018;97:e9656. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009656. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Zhang J., Hong L., Ma G. Socioeconomic Status, Peer Social Capital, and Quality of Life of High School Students During COVID-19: A Mediation Analysis. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 2022;17:3005–3021. doi: 10.1007/s11482-022-10050-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Wang J., Geng L. Effects of socioeconomic status on physical and psychological health: Lifestyle as a mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:281. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16020281. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. McMaughan D.J., Oloruntoba O., Smith M.L. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:231. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00231. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Daniel H., Bornstein S.S., Kane G.C. Addressing Social Determinants to Improve Patient Care and Promote Health Equity: An American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;168:577–578. doi: 10.7326/M17-2441. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Muhammad T., Kumar P., Srivastava S. How socioeconomic status, social capital and functional independence are associated with subjective wellbeing among older Indian adults? A structural equation modeling analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1836. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14215-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Chen Q., Kong Y., Gao W., Mo L. Effects of Socioeconomic Status, Parent–Child Relationship, and Learning Motivation on Reading Ability. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1297. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01297. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Al-Omoush K.S., Ribeiro-Navarrete S., Lassala C., Skare M. Networking and knowledge creation: Social capital and collaborative innovation in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022;7:100181. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2022.100181. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Sengupta N.K., Osborne D., Houkamau C.A., Hoverd W.J., Wilson M.S., Greaves L.M., West Newman T., Barlow F.K., Armstrong G., Robertson A., et al. How much happiness does money buy? Income and subjective well-being in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2012;41:21–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Puntscher S., Hauser C., Walde J., Tappeiner G. The impact of social capital on subjective well-being: A regional perspective. J. Happiness Stud. 2015;16:1231–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9555-y. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Gu D., Brown B.L., Qiu L. Self-perceived uselessness is associated with lower likelihood of successful aging among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:172. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0348-5. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Green H., Fernandez R., Moxham L., MacPhail C. Social capital and wellbeing among Australian adults’ during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:2406. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14896-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (970.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Development

An Overview of the 8th Annual QER Conference (21-22 August 2024)

Resep quantitative analysis course in the economics of education, assessment matters: what can we understand about the national senior certificate results during covid-19 from university entrance exams.

Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP) is a group of scholars and students interested in issues of poverty, income distribution, social mobility, economic development and social policy. Based at the Department of Economics at the University of Stellenbosch. The team is lead by Servaas van der Berg, whose position as the Chair in the Economics of Social Policy since 2008, has lead to the further consolidation of research within these areas.

Recent Papers

The latest working papers, publications, reports and policy briefs by resep researchers..

A brief look behind the flat 2015 to 2019 TIMSS Grade 5 trend for South Africa

Repetition and dropout in south africa before, during and after covid-19, covid-19 and inequality in reading outcomes in south africa: pirls 2016 and 2021, ongoing projects.

RESEP has received funding for its research from various organisations and governments. In recent years, funding for research has been provided by, amongst others, Allan & Gill Gray Philanthropies, FEM Education Fund, the Epoch & Optima Trusts, The UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC); UNICEF offices in South Africa, Namibia and Eswatini; Zenex Foundation, Tshikululu Social Investments, PSPPD (Presidency/European Union) and the National Research Foundation (NRF).

Contact Information

Email: carinebrundson@ null sun.ac.za Phone: (+27) 21 808 2024

Research on Socio-Economic Policy (RESEP) Department of Economics Matieland 7602

Sign Up for our Newsletter

© 2024 Research on Socio-Economic Policy (RESEP). All rights reserved

- Publications

- Reports & Policy Briefs

- Working Papers

- Historical Resources

- Open access

- Published: 05 December 2024

Analysis of how a complex systems perspective is applied in studies on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour—a call for reporting guidelines

- Andrea L. Mudd 1 ,

- Michèlle Bal 1 ,

- Sanne E. Verra 1 ,

- Maartje P. Poelman 2 &

- Carlijn B. M. Kamphuis 1

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 22 , Article number: 160 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

172 Accesses

Metrics details

A complex systems perspective is gaining popularity in research on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour, though there may be a gap between its popularity and the way it is implemented. Building on our recent systematic scoping review, we aim to analyse the application of and reporting on complex systems methods in the literature on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour.

Selected methods and results from the review are presented as a basis for in-depth critical reflection. A traffic light-based instrument was used to assess the extent to which eight key concepts of a complex systems perspective (e.g. feedback loops) were applied. Study characteristics related to the applied value of the models were also extracted, including the model evidence base, the depiction of the model structure, and which characteristics of model relationships (e.g. polarity) were reported on.

Studies that applied more key concepts of a complex systems perspective were also more likely to report the direction and polarity of relationships. The system paradigm, its deepest held beliefs, is seldom identified but may be key to recognize when designing interventions. A clear, complete depiction of the full model structure is also needed to convey the functioning of a complex system. We recommend that authors include these characteristics and level of detail in their reporting.

Conclusions

Above all, we call for the development of reporting guidelines to increase the transparency and applied value of complex systems models on socioeconomic inequalities in health, health behaviour and beyond.

Graphical Abstract

Peer Review reports

In the past 20 years, interest in applying a complex systems perspective to understanding the dynamics underlying socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour has grown (e.g. [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]). A complex systems perspective combines systems theory and complexity science, in which health outcomes are considered to be an emergent property of the system as a whole [ 5 ]. Complex systems models include factors at multiple levels of influence and specify feedback loops between these factors. This sets complex systems models apart from most traditional approaches to studying socioeconomic inequalities in health, which often focus on linear relationships between single factors (e.g. quality of neighbourhood infrastructure) and lead to policy recommendations centring around single factors and outcomes (e.g. physical activity) [ 5 ]. For example, in an approach grounded in a complex systems perspective, the ways in which the quality of neighbourhood infrastructure is intertwined with other resources neighbourhood residents have access to (e.g. money, time or social support), prevailing cultural norms in the neighbourhood and how residents use the available infrastructure (for physical activity and other behaviours, e.g. socializing or consuming alcohol) may be viewed as just one part of what drives socioeconomic inequalities in health in that community. The parts or mechanisms in a complex system come together as more than the sum of their parts, in nonlinear and sometimes unexpected ways to influence the system’s behaviour (here, socioeconomic inequalities in health). Adopting a complex systems perspective may more effectively depict the complexity of real life processes, supporting public health policymakers and other stakeholders in meeting the challenges posed by systematic socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour [ 6 ].

A complex systems perspective also introduces new analytical and conceptual challenges to understanding and modelling real-life processes, creating a potential gap between awareness about the usefulness of a complex systems approach and its implementation in research [ 7 ]. Taking stock of how existing studies on socioeconomic inequalities in health have applied a complex systems perspective may reveal opportunities for this important field of research to continue developing.

In our recent systematic scoping review [ 8 ], we provided an overview of 42 studies that modelled socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour from a complex systems perspective using conceptual models, simulation models or both. Conceptual methods to modelling a complex system entail representing the system’s causal structure, and simulation methods entail formalizing and quantifying the system’s causal structure (e.g. agent-based models or systems dynamics models) [ 1 ]. The main focus of the systematic scoping review was to summarize and analyse the content of the identified models. In the content-focused review, we assessed the quality of included studies by evaluating the evidence each complex systems model was based on and the extent to which key concepts of a complex systems perspective were applied. During this quality assessment process, we found that key concepts of a complex systems approach were applied to varying degrees. During the review process, we also noticed that certain reporting styles aided our ability to understand the model structures in the studies we identified, while other reporting styles hindered our understanding. Clear reporting styles, in our view, are crucial for the interpretability and applied value of complex systems models, both for researchers and in practice (e.g. to inform the selection of policies). Given these preliminary observations, additional critical reflection on how complex systems methods have been applied on the subject of socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour and how these methods have been reported on in publications is warranted [ 4 ]. This critical reflection on the application of and reporting on complex systems methods is the focus of this manuscript.

In this short manuscript, we aim to analyse how the studies identified in our systematic scoping review applied complex systems methodologies and how these studies reported on the methods applied. In this analysis, we [ 1 ] assess and critically discuss current applications of a complex systems perspective in the literature on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour and [ 2 ] provide recommendations for the development of comprehensive reporting guidelines, aimed at improving the transparency and applied value of future complex systems models. This short manuscript is based on data extracted in the process of conducting our systematic scoping review [ 8 ]. In order for this manuscript to function as a stand-alone piece, selected methods and results related to the application of a complex systems approach that are published elsewhere are briefly repeated here. What this manuscript adds to existing literature is an in-depth analysis and critical reflection on how complex systems methods were applied and reported on.

The complete methodology for the systematic scoping review, which adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist, can be found in the main manuscript [ 8 ]. In short, we searched SCOPUS, Web of Science and PubMed from database start dates to April 2023 for studies that: [ 1 ] concern the adult general population in high-income countries belonging to the OECD [ 2 , 9 ], contain an original or adapted conceptual or simulation model, [ 3 ], self-identify as having applied a complex systems perspective [ 4 ], include a measure of socioeconomic position and [ 5 ] include a health or health behaviour outcome relevant for the adult general population.

A traffic light-based instrument was used to assess the extent to which key concepts of a complex systems perspective were incorporated into the studies identified in our scoping review. Key concepts of a complex systems perspective were selected from prominent literature about complex systems in the context of socioeconomic inequalities in health [ 1 , 10 ] along with literature about complex systems more generally [ 11 , 12 ]. The format of our instrument was based on an existing traffic light-based instrument developed to assess the application of a complex systems perspective in public health-related process evaluations [ 13 ]. The eight key concepts included in our instrument are presented in Table 1 .

For each included study, the application of each key concept was assessed using green, yellow and red traffic lights. Green was used when a concept was explicitly incorporated into the model, meaning that the authors described that the concept was applied and how they applied it. Yellow was used when a concept seemed to have been incorporated into the model, but this was not clearly described in the publication. Red was used when a concept was not incorporated into the model.

In addition to the key concepts of a complex systems perspective, several extracted study characteristics related to the applied value of the complex systems models identified in the literature are especially relevant for this analysis. These include the evidence the model (including the model structure and, if relevant, model operationalization) was based on, how the model was presented in the manuscript (i.e. diagram, text or table) and characteristics of the relationships in the model. Relationship characteristics included the direction (going to and from certain model elements), polarity (positive or negative) and magnitude (strength) of the relationships.

Data extraction, including the assessment of the application of key concepts of a complex systems approach, was performed by one reviewer (A.M.). Two reviewers (S.V. and M.P.) validated the data extraction on a total of 20% of the included studies. Any discrepancies were discussed between reviewers (and, if needed, the full research team) until agreement was reached, and insights from these discussions were applied to the data extracted from all studies included in the review.

Complex systems methods-related results from the systematic scoping review

Table 2 provides an overview of the extent to which the 42 studies included in the systematic scoping review [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 ] applied key concepts of a complex systems perspective and characteristics related to the studies’ applied value. As presented in the systematic scoping review [ 8 ], key concepts of a complex systems perspective included in our traffic light assessment were applied to varying degrees, and only five studies explicitly applied all key concepts [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ].

About half ( N = 23) of the included studies clearly described how the modelled relationships were based on literature, empirical study, iterative model building processes or a combination of these; for the other half, the model evidence base was less clear (Table 2 ). All studies containing a conceptual model were explicit about the model structure in the sense that they included a diagram of the model structure (e.g. a causal loop diagram), whereas about half of studies containing a simulation model included a diagram. A total of 86% of studies reported the direction of relationships between model elements, 62% reported on polarity and only 24% of studies reported on magnitude. Simulation models contained more detail about the modelled relationships than conceptual models, though conceptual models were not expected to report the magnitude of relationships (direction 95% versus 75%, polarity 77% versus 45%, magnitude 45% versus 0%).

Further analysis and critical reflection

Critical appraisal of how a complex systems perspective was applied in literature.

One reason that studies containing simulation models may have applied key concepts of a complex systems approach more consistently than studies containing only conceptual models may be the existence of reporting standards for specific types of simulation models. For instance, the overview, design concepts and details protocol (ODD) for agent-based models is widely cited and includes questions about key concepts of complex systems thinking, such as emergence and adaptation [ 19 , 20 ]. In our analyses, we observed that adaptation was explicitly addressed in 82% of simulation studies (versus 25% of conceptual studies), and emergence was explicitly addressed in 50% of simulation studies (versus 25% of conceptual studies). Still, 50% of simulation studies explicitly considering emergence is not very high, and in fact, the agent-based models included in our review were less likely to consider emergence than other types of simulation models. It seems that, although guidelines such as the ODD protocol are important for the reproducibility and understandability of models, these guidelines may not yet be widely used in agent-based models on socioeconomic inequalities in health.

Studies that applied more key concepts of a complex systems perspective were more likely to report the direction and polarity of the modelled relationships. To investigate this more closely, we estimated Spearman correlations between the percentage of key concepts that were explicitly considered in a model and whether relationship direction, polarity and both direction and polarity were reported on. These additional calculations showed that the percentage of key concepts explicitly considered in a model was positively correlated with reporting the direction (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.43, P value < 0.001), polarity (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.58, P value < 0.001) and combined direction and polarity of relationships (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.60, P value < 0.001). Reporting on direction and polarity increases the applied value of complex systems models. Specifically, knowing whether a model element has a positive or negative influence on health is crucial to understanding model relationships, feedback loops and the functioning of the system as a whole. In our scoping review, reported relationship direction and polarity allowed us to meaningfully interpret shared drivers of socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour and to summarize the existing literature in a causal loop diagram. It could be beneficial to include whether studies report on the direction and polarity of model relationships in assessments of the application of a complex systems perspective in future research. This would go a step further than our traffic light-based assessment of whether (but not how) connections or interactions between system elements were specified.

A key concept of a complex systems perspective that we did not include in our traffic light-based instrument but that may be important to consider is the system paradigm. A complex system’s paradigm is the mindset out of which the system arises or its deepest held belief [ 21 , 22 ]. The system’s paradigm is the source of its overarching goals, which the system can adapt towards over time [ 22 ]. One study included in the scoping review analysed and described the system paradigm: Sawyer and colleagues found that the dynamic system underlying the food environment and its influence on dietary intake in low-income groups was driven by an economic paradigm, with ‘the need for economic prosperity as the system’s deepest held belief’ (15, p.10). This paradigm was elucidated by analysing how the model subsystems were interconnected and related to key dimensions of the food environment. According to the Intervention Level Framework, intervening on the system paradigm has the highest potential for impact on the system, whereas intervening on individual system elements has the lowest potential impact [ 22 ]. Despite its purported importance, very few policy recommendations or interventions are aimed at system paradigms, and neither our assessment or other existing assessments of the application of a complex systems perspective included system paradigm as a key concept of a complex systems perspective. This may be because identifying the system’s paradigm is inherently complex. There is no singular strategy for identifying the system’s paradigm, as understanding a system’s paradigm requires thorough and meaningful engagement with the functioning of a complex system. Indeed, building a model of a complex system compels us to view the system as a whole, bringing the system’s goals and paradigm to the surface [ 21 , 22 ]. As the field develops further, researchers should seek to identify the system paradigm when analysing and assessing complex systems models, as understanding the system paradigm may help bring the most useful and effective policy levers to light.

Finally, including a clear and complete depiction of the model structure was important for assessing the extent to which a complex systems perspective was applied and for being able to extract useful information about the model content. Most diagrams included in simulation studies represented the general model structure, and details about the formalized model were provided in text. Studies containing conceptual models were more likely to include explicit descriptions of the model development process and the evidence the model structure was based on (e.g. literature or stakeholder sessions). On the other hand, studies containing simulation models usually included descriptions of the evidence informing the model parameterization (often empirical data), but the evidence underpinning the chosen model structure itself was often vague or missing. In some cases, text-only descriptions were incomplete, making it challenging to interpret model relationships, and in other cases, diagrams on their own may not be informative enough to understand the model relationships (e.g. if relationship polarity is not indicated in the diagram). Diez Roux emphasized the importance of describing the model structure for conceptual and simulation studies alike: ‘Any systems approach must begin with the development of what has been referred to as a mental model’ (1, p.1631). In the process of extracting model relationships from the included studies, we experienced that it was easier to understand the model if both a diagram and some text describing important model dynamics was available.

Call for reporting guidelines

Based on this critical appraisal of how conceptual and simulation-based complex systems approaches were applied in the literature on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour, we call for the development of reporting guidelines for studies that aim to apply a complex systems perspective. Guidelines on reporting standards for a broad range of complex systems models would benefit researchers, those developing models and those interpreting (or aiming to build upon) study findings alike. These guidelines could focus on making the authors’ approach and the model structure understood by readers. In this way, the guidelines would complement rather than replace existing guidelines, such as the ODD protocol [ 19 , 20 ] or the recently published guidance on the use of complex systems models for economic evaluations of public health interventions [ 23 ]. These existing guidelines are more focused on technical aspects of simulation modelling or the development of simulation models for specific purposes (e.g. economic evaluation). In Box 1, we propose some initial recommendations for researchers aiming to apply a complex systems perspective to understanding socioeconomic inequalities in health and beyond, informed by the analysis presented in this manuscript. These suggestions are far from exhaustive and should be expanded on and formalized as comprehensive reporting guidelines. Adherence to such guidelines would likely improve the quality, understandability and applied value of future complex systems models for understanding and tackling socioeconomic inequalities in health.

Box 1: recommendations for researchers aiming to apply a complex systems perspective

Explicitly describe how a complex systems perspective was incorporated in the model

Explicitly describing which concepts of a complex systems perspective were incorporated into the presented model and which ones were not applied and why, will make the alignment between the study aim and the applied method clearer. Below is a list of characteristics of a complex systems perspective that could be described:

- Heterogeneous elements

- Relationships between elements, including the direction and polarity of the relationships

- Presence of feedback loops between elements

- Interactions between system levels

- Adaptation

- Emergence

- Nonlinear dynamics

- System paradigm

Describe the process of developing the conceptual model and the evidence base underlying the model relationships

Many different approaches exist for developing conceptual complex systems models, including group model building sessions, literature review, expert knowledge or any combination of these [ 24 ]. Knowing more about the development process is essential for the reader to be able to understand the context the model was built in (i.e. what are the perspectives and positionalities of the model developers?) and to assess the validity of the model. This recommendation applies to conceptual and simulation studies alike, as, ideally, the structure of a simulation model is based on a conceptual model

Include a diagram depicting the model structure in its entirety

The inclusion of a complete and informative diagram, such as a causal loop diagram, ensures that readers are able to understand the full model structure. Text-only descriptions can leave gaps in understanding, making it challenging to interpret model relationships and making model outcomes less reliable to the reader. Textual descriptions of the model structure can, however, complement a diagram, especially when authors wish to provide information on the relative importance or magnitude of certain model elements or relationships

In this short manuscript, we analysed how complex systems methods were used and reported on in existing studies on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour, in which authors reported applying a complex systems perspective. While key concepts of a complex systems perspective were applied to varying degrees, we found that more thorough reporting on how a complex systems perspective was applied increased the understandability and applied value of models. Specifically, describing how key concepts of a complex systems perspective were applied, providing details about model relationships and presenting a clear justification for and depiction of the full model structure all increased the ability to understand the functioning of complex systems models. While we present reporting-related recommendations for researchers based on our analysis, we emphasize the need for the development of comprehensive reporting guidelines to increase the transparency and applied value of complex systems models on topics related to socioeconomic inequalities in health, health behaviour and beyond.

Availability of data and materials

The full search strings and key study and model characteristics are available in the manuscript reporting the content-related findings of the systematic scoping review. Findings from the assessment of the assessment of the application of a complex systems perspective and from the assessment of the evidence base are available in Table 2 .

Abbreviations

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Overview, Design concepts, Details protocol

Diez Roux AV. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1627–34.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wilderink L, Bakker I, Schuit AJ, Seidell JC, Pop IA, Renders CM. A theoretical perspective on why socioeconomic health inequalities are persistent: building the case for an effective approach. IJERPH. 2022;19(14):8384.

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12): e009002.

Jayasinghe S. Social determinants of health inequalities: towards a theoretical perspective using systems science. Int J Equity Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0205-8 .

Kaplan GA, Diez Roux AV, Simon CP, Galea S. Growing inequality: bridging complex systems, population health and health disparities. Washington, DC: Westphalia Press; 2017. p. 332.

Google Scholar

Salway S, Green J. Towards a critical complex systems approach to public health. Crit Public Health. 2017;27(5):523–4.

Article Google Scholar

Mudd AL, Bal M, Verra SE, Poelman MP, de Wit J, Kamphuis CBM. The current state of complex systems research on socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behavior—a systematic scoping review. Int J Behav Nutrit Phys Act. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-024-01562-1 .

OECD. Country classification 2022—as of 3 August 2022. OECD. 2022. https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/export-credits/documents/2022-cty-class-en-(valid-from-03-08-2022).pdf . Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Rutter H, Cavill N, Bauman A, Bull F. Systems approaches to global and national physical activity plans. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(2):162–5.

Carmichael T, Hadžikadić M. The fundamentals of complex adaptive systems. In: Carmichael T, Collins AJ, Hadžikadić M, editors. complex adaptive systems. Cham: Springer; 2019.

Chapter Google Scholar

Holden LM. Complex adaptive systems: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(6):651–7.

McGill E, Marks D, Er V, Penney T, Petticrew M, Egan M. Qualitative process evaluation from a complex systems perspective: a systematic review and framework for public health evaluators. PLoS Med. 2020;17(11):e1003368.

Mooney SJ, Shev AB, Keyes KM, Tracy M, Cerdá M. G-computation and agent-based modeling for social epidemiology: can population interventions prevent posttraumatic stress disorder? Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(1):188–97.

Salvo D, Lemoine P, Janda KM, Ranjit N, Nielsen A, Van Den Berg A. Exploring the impact of policies to improve geographic and economic access to vegetables among low-income, predominantly Latino urban residents: an agent-based model. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):646.

Broomhead T, Ballas D, Baker SR. Neighbourhoods and oral health: agent-based modelling of tooth decay. Health Place. 2021;71: 102657.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Occhipinti JA, Skinner A, Iorfino F, Lawson K, Sturgess J, Burgess W, et al. Reducing youth suicide: systems modelling and simulation to guide targeted investments across the determinants. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):61.

Yang Y, Langellier BA, Stankov I, Purtle J, Nelson KL, Diez Roux AV. Examining the possible impact of daily transport on depression among older adults using an agent-based model. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(6):743–51.

Blok DJ, Van Lenthe FJ, De Vlas SJ. The impact of individual and environmental interventions on income inequalities in sports participation: explorations with an agent-based model. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):107.

Chen HJ, Xue H, Liu S, Huang TTK, Wang YC, Wang Y. Obesity trend in the United States and economic intervention options to change it: a simulation study linking ecological epidemiology and system dynamics modeling. Public Health. 2018;161:20–8.

Li Y, Zhang D, Thapa JR, Madondo K, Yi S, Fisher E, et al. Assessing the role of access and price on the consumption of fruits and vegetables across New York City using agent-based modeling. Prev Med. 2018;106:73–8.

Zhang Q, Northridge ME, Jin Z, Metcalf SS. Modeling accessibility of screening and treatment facilities for older adults using transportation networks. Appl Geogr. 2018;93:64–75.

Orr MG, Kaplan GA, Galea S. Neighbourhood food, physical activity, and educational environments and black/white disparities in obesity: a complex systems simulation analysis. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2016;70(9):862–7.

Blok DJ, De Vlas SJ, Bakker R, Van Lenthe FJ. Reducing income inequalities in food consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):605–13.

Brittin J, Araz OM, Nam Y, Huang TK. A system dynamics model to simulate sustainable interventions on chronic disease outcomes in an urban community. J Simulat. 2015;9(2):140–55.

Homa L, Rose J, Hovmand PS, Cherng ST, Riolo RL, Kraus A, et al. A participatory model of the paradox of primary care. Ann Family Med. 2015;13(5):456–65.

Yang Y, Auchincloss AH, Rodriguez DA, Brown DG, Riolo R, Diez-Roux AV. Modeling spatial segregation and travel cost influences on utilitarian walking: towards policy intervention. Comput Environ Urban Syst. 2015;51:59–69.

Orr MG, Galea S, Riddle M, Kaplan GA. Reducing racial disparities in obesity: simulating the effects of improved education and social network influence on diet behavior. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(8):563–9.

Zhang D, Giabbanelli PJ, Arah OA, Zimmerman FJ. Impact of different policies on unhealthy dietary behaviors in an urban adult population: an agent-based simulation model. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1217–22.

Lymer S, Brown L. Developing a dynamic microsimulation model of the Australian health system: a means to explore impacts of obesity over the next 50 years. Epidemiol Res Int. 2012;2012:1–13.