- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 01 April 2021

Unethical practices within medical research and publication – An exploratory study

- S. D. Sivasubramaniam 1 ,

- M. Cosentino 2 ,

- L. Ribeiro 3 &

- F. Marino 2

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 17 , Article number: 7 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

2 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

The data produced by the scientific community impacts on academia, clinicians, and the general public; therefore, the scientific community and other regulatory bodies have been focussing on ethical codes of conduct. Despite the measures taken by several research councils, unethical research, publishing and/or reviewing behaviours still take place. This exploratory study considers some of the current unethical practices and the reasons behind them and explores the ways to discourage these within research and other professional disciplinary bodies. These interviews/discussions with PhD students, technicians, and academics/principal investigators (PIs) (N=110) were conducted mostly in European higher education institutions including UK, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, Czech Republic and Netherlands.

Through collegiate discussions, sharing experiences and by examining previously published/reported information, authors have identified several less reported behaviours. Some of these practices are mainly influenced either by the undue institutional expectations of research esteem or by changes in the journal review process. These malpractices can be divided in two categories relating to (a) methodological malpractices including data management, and (b) those that contravene publishing ethics. The former is mostly related to “committed bias”, by which the author selectively uses the data to suit their own hypothesis, methodological malpractice relates to selection of out-dated protocols that are not suited to the intended work. Although these are usually unintentional, incidences of intentional manipulations have been reported to authors of this study. For example, carrying out investigations without positive (or negative) controls; but including these from a previous study. Other methodological malpractices include unfair repetitions to gain statistical significance, or retrospective ethical approvals. In contrast, the publication related malpractices such as authorship malpractices, ethical clearance irregularities have also been reported. The findings also suggest a globalised approach with clear punitive measures for offenders is needed to tackle this problem.

Introduction

Scientific research depends on effectively planned, innovative investigation coupled with truthful, critically analysed reporting. The research findings impact on academia, clinicians, and the general public, but the scientific community is usually expected to “self-regulate”, focussing on ethical codes of conduct (or behaviour). The concept of self-regulation is built-in from the early stages of research grant application until the submission of the manuscripts for gaining impact. However, increasing demands on research esteem, coupled with the way this is captured/assessed, has created a relentless pressure to publish at all costs; this has resulted in several scientific misconduct (Rawat and Meena 2014 ). Since the beginning of this century, cases of blatant scientific misconduct have received significant attention. For example, questionable research practices (QRP) have been exposed by whistle blowers within the scientific community and publicised by the media (Altman 2006 ; John et al. 2012 ). Moreover, organisations such as the Centre for Scientific Integrity (CSI) concentrate on the transparency, integrity and reproducibility of published data, and promote best practices (www1 n.d. ). These measures focus on “scholarly conduct” and promote ethical behaviour in research and the way it is reported/disseminated, yet the number of misconduct and/or QRP’s are on the rise. In 2008, a survey amongst researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suggested there might be as many as 1,000 cases of potential scientific misconduct going unreported each year (Titus et al. 2008 ). Another report on bioRxiv (an open access pre-print repository) showed 6% of the papers (59 out of 960) published in one journal (Molecular and Cellular Biology - MCB), between 2009 and 2016, contained inappropriately duplicated images (Bik et al. 2018 ). Brainard ( 2018 ) recently reported that the number of articles retracted by scientific journals had increased 10-fold in the past 10 years. If the reported incidence of scientific misconduct is this high, then one can predict the prevalence of other, unreported forms of misconduct. The World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) has identified the following as the most reported misconduct: fabrication, falsification, plagiarism/ghost writing, image/data manipulation, improprieties of authorship, misappropriation of the ideas of others, violation of local and international regulations (including animal/human rights and ethics), inappropriate/false reporting (i.e. wrongful whistle-blowing) (www2 n.d. ).

However, WAME failed to identify other forms of scientific misconduct, such as; reviewer bias (including reviewers’ own scientific, religious or political beliefs) (Adler and Stayer 2017 ), conflicts of interests (Bero 2017 ), and peer-review fixing, which is widespread, especially after the introduction of author appointed peer reviewers (Ferguson et al., 2014 ; Thomas 2018 ). The most recent Retraction Watch report has shown that more than 500 published manuscripts have been retracted due to peer-review fixing; many of these are from a small group of authors (cited in Meadows 2017 ). Other reasons for retraction include intentional/unintentional misconduct, fraud and to a lesser extent honest errors. According to Fang et al. ( 2012 ), in a detailed study using 2,047 retracted articles within biomedical and life-sciences, 67.4% of retractions were due to some form of misconduct (including fraud/suspected fraud, duplicate publication, and plagiarism). Only 21.3% of retractions were due to genuine error. As can be seen, most of the information regarding academic misconduct is reported, detected or meta-analysed from databases. As for reporting (or whistle blowing), many scientists have shown been reticent to raise concerns, mainly because of the fear of aftermath or implications of doing so (Bouter and Hendrix 2017 ). An anonymous information-gathering activity amongst scientists, junior scientists, technicians and PhD students may highlight the misconduct issues that are being encountered in their day-to-day laboratory, and scholarly, activities. Therefore, this exploratory study of an interview-based study reports potentially un-divulged misconduct and tries to form a link with previously reported misconduct that are either being enforced, practiced or discussed within scientific communities.

Methodology

This qualitative exploratory study was based on informal mini-interviews conducted through collegiate discussions with technicians, PhD scholars, and fellow academics (N=110) within medical and biomedical sciences mainly in European higher education institutions including UK, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, Czech Republic and Netherlands (only 5 PhD students). PhD students (n=75), technicians (mostly in the UK; n=25) and academics/principal investigators (PIs; n=10), around Europe, have taken part in this qualitative narrative exploration study. These mini-interviews were carried out in accordance with local ethical guidance and processes. The discussions or conversations were not voice recorded; nor the details of interviewees taken to maintain anonymity. The data was captured (in long-hand) by summarising their views on following three questions (see below).

These answers/notes were then grouped according to their similarities and summarised (see Tables 1 and 2 ). The mini-interviews were semi-structured, based around three questions.

Have you encountered any individual or institutional malpractices in your research area/laboratory?

If so, could you give a short description of this misconduct?

What are the measures, in your opinion, needed to minimise or remove these misconduct?

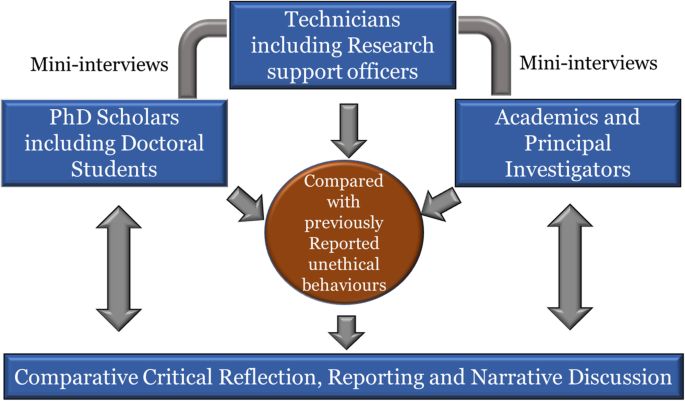

we also examined recently published and/or reported (in media) unethical practice or misconduct to compare our findings (see Table 2 ). Fig. 1 summarises the methodology and its meta-cognitive reflection (similar to Eaton et al. 2019 ).

Interactive enquiry-based explorative methodology used in this study

Results and discussion

As stated above, this manuscript is an exploratory study of unethical practice amongst medical researchers that are not well known or previously reported. Hence, the methodology applied was more exploratory with minimal focus on standardisation, using details of qualitative approach and paradigm, or the impact of researcher characteristics and reflexivity (British Medical Journal (BMJ) – www3 n.d. ). Most importantly, our initial informal meetings prior to this study clearly indicated that the participants were reluctant to provide information that would assist for an analysis linked to researcher characteristics and/or reflexivity. Thus, the level of data presented herein would not be suitable for a full thematic analysis. We do accept this as a research limitation.

This study has identified some less reported (not well-known) unethical behaviours or misconduct. These findings from technician/PhD scholars and academics/PIs are summarised in Tables 1 and 2 . The study initially aimed to identify any previously unreported unethical research conducts, however, the data shows that many previously identified misconduct are still common amongst researchers. Since the interviews were not audio recorded (to reassure anonymity), the participants were openly reported the unethical practices within their laboratories (or elsewhere). This may cast doubts on the accuracy of data interpretation. To minimise this, we have captured the summary of the conversation in long-hand.

We were able to generalise two emerging themes linked to the periods of a typical research cycle (as described by Hevner 2007 ); (a) methodological malpractices (including data management), and (b) those that contravene publishing ethics. Researcher-linked behaviours happen during laboratory investigation stage, where researchers employ questionable research practices, these include self-imposed as well as acquired (or taught) habits. As can be seen from Tables 1 and 2 , these misconduct are mainly carried out by either PhD scholars, post-doctoral scientists or early career researchers. These reported “practices” may be common amongst laboratory staff, especially given the fact that some of these practices have been nicknamed (e.g. ghost repeats, data mining etc. – see Table 1 ). Individual or researcher-linked unethical behaviours mostly related to “committed bias”, by which the researcher selectively uses the data to suit their own hypothesis or what they perceive as ground-breaking. This often results in conducts where research (and in some cases data/results) is statistically manipulated to suit the perceived conclusion.

Although this is a small-scale pilot study, we feel this reflects the common trend in laboratory-based research. As mentioned earlier, although this study was set out to detect unreported research misconduct/malpractices, study participant reported some of the behaviours that were already reported in previous studies.

In contrast, established academics, professors and PIs tend to commit publication-related misconduct. These can be divided into author-related or reviewer-related misconduct. The former includes QRPs during manuscript preparation (such as selective usage of data, omitting outliers, improper ethical clearance, authorship demands etc). The latter is carried out by the academics when they review others manuscripts and includes delaying review decisions, reciprocal reviewing etc.

From tables above, it seems that most of the reported misconduct can be easily prevented if specific and accurate guidelines or code of conduct are present in each research laboratory (see below). This aspect, for example is of minor impact in the clinical research, where the study protocol is rigorously detailed in advance, the specific analysis that will be included in the final report specified in advance with clear primary or secondary endpoints, and all the analysis/reports need to be stored for the final study revision/conclusion. All these different steps are regulated by Good Clinical Practice guidelines (GCP; National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN- www4 n.d. ).

This by no means indicates that in clinical research fraud does not exist, but that it is easier to discover it than in laboratory based-investigations. The paper of Verhagen et al. ( 2003 ) clearly refers to a specific situation that commonly happens in a research laboratory. The majority of experiments within biomedical research are conducted on tissues or cells. Therefore, the experimental set-ups, including negative and positive controls can easily (and frequently) be manipulated. This can only be prevented by using Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) and well written and clear regulation such as Good Laboratory Practice (GLP; Directive 2004 /9/EC), and written protocols. However, at present, no such regulations exist apart from in industry-based research, where GLP is mandatory. In a survey-based systematic review, Fanelli ( 2009 ) reported that approximately 2% of scientists claimed they had fabricated their data, at some point in their research career. It is worth noting, Fanelli’s study (as well as ours) only reported data from those who were willing admit engaging in these activities. This cast questions on actual number of occurrences, as many of them would not have reported misconduct. Other authors have highlighted the same issue and cast doubt on the reproducibility of scientific data (Resnik and Shamoo, 2017 ; Brall et al, 2017 ; Shamoo 2016 ; Collins and Tabak 2014 ; Kornfeld and Titus 2016 ).

The interview responses

We also wanted to understand the causes of these QRPs to obtain a clear picture of these misconduct. Based on interview responses, we have tried to give a narrative but critical description of individual perceptions, and their rationalisation in relation to previously published information.

Methodological malpractices

The data reported herein show that PhD scholars/post-doctoral fellows are mostly involved in laboratory-linked methodological misconduct. Many of them (especially the post-doctoral scientists) blamed supervisory/institutional pressures on not only enhancing publishing record, but also maintaining high impact. One post-doctoral scientist claimed “ there is always a constant pressure on publication; my supervisor said the reason you are not producing any meaningful data is because you are a perfectionist ”. He further recalled his supervisor once saying “ if the data is 80% correct, you should accept it as valid and stop repeating until you are satisfied ”.

Likewise, another researcher who recently returned from the US said “ I was an excellent researcher here (home country), but when I went to America, they demanded at least one paper every six months ”. “ When I was unable to deliver this (and missed a year without publishing any papers), my supervisor stopped meeting me, I was not invited for any laboratory meetings, presentations, and proposal discussions; in fact, they made me quit the job ”. A PhD student recalled his supervisor jokingly hinting “ if you want a perfect negative control, use water it will not produce any results ”. Comments and demands like these must have played a big role in encouraging laboratory based misconduct. In particular, the pressure to publish more papers in a limited period led to misconduct such as data manipulation (removing outliers, duplicate replications, etc.) or changing the aim of the study, and as a consequence including data set that were not previously considered, because the results are not in line with the original aim of the study. All these aspects force the young researchers to adopt an attitude that leads them to obtain publishable results by any means (ethical or not) – A “ Machiavellian personality trait ” as put by Tijdink et al. ( 2016 ). Indeed, an immoral message is being delivered to these young researchers (future scientists), enhancing cheating behaviours. In fact, Buljan et al. ( 2018 ) have recently highlighted the research environment, in which a scientist is working, as one of the potential causes of misconduct.

Behaviours that contravene publishing ethics

Academics (and PIs) have mostly identified misconduct linked to contravening publishing ethics. This finding itself shows that most of the academics who took part in this study has less “presence” within their laboratories. When confronted with the data obtained from PhD scholars and technicians, some of them vehemently denied these claims. Others came up with a variety of excuses. One lecturer/researcher said, “ I have got far too much teaching to be in my laboratory ”. Another professor said, “ I have post-docs within my laboratory, they will look after the rest; to be honest, my research skills are too old to refresh!” One PI replied, “ why should I check them? No one checked me when I was doing research ”. All these replies show a lack of care for research malpractices. It is true that academics are under pressure to deliver high impact research, carry out consultancy work, get involved with internationalisation within academia and teach (Edwards and Roy 2017 ). However, these pressures should not undermine research ethics.

One researcher claimed to have noticed at least two different versions of “ convenient ethical clearance ”. According to him, some researchers, especially those using human tissues, avoid specifying their research aims; and instead write an application in such a way that they can use these samples for a variety of different projects (bearing in mind of possible future developments). For example, if they aim to use the tissue to study a particular protein, the ethical application would mention all the related proteins and linked pathways. They justify this by claiming the tissues are precious, therefore they are “ maximising the effective use of available material ”. Whilst understanding the rationale within their argument, the academic who witnessed this practice asked a question “ how ethical it is to supply misleading information in an ethical application ?” He also highlighted issues with backdating ethical approval in one institution. That is, the ethical approval was obtained (or in his words “ staged ”) after the study has been completed. Although this is one incident reported by one whistle-blower, it highlights the institutional malpractices.

Selective use of data is another category reported here and elsewhere (Priya Satalkar & David Shaw, 2019 ; Blatt 2013 ; Bornmann 2013 ). One academic reported incidences of researchers purposely avoiding data to maximise the statistical significance. If this is the case, then the validity of reported work, its statistical significance, and in some cases its clinical usage are in question. What is interesting is that, as elegantly reported by Fanelli ( 2010 ), in the highest percentage of published papers, the findings always report the data that are in line with the original hypothesis. In fact, the number of papers published reporting negative results are very limited.

Misconduct relating to authorships have been highlighted in many previous studies (Ploug 2018 ; Vera-Badillo et al. 2016 ; Ng Chirk Jenn 2006 ). The British Medical Journal (BMJ – www5 n.d. ) has classified two main types of misconduct relating to authorships; (a) omission of a collaborator who has contributed significantly to the project and (b) inclusion of an author who has not (or minimally) contributed. Interestingly in this study, one academic claimed that he was under pressure to include the research co-ordinator of his department as an author in every publication.

He recalled the first instance when he was pressurised to include the co-ordinator, “ It was my first paper as a PI but due to my institutional policy, all potential publications needed to be scrutinised by the co-ordinator for their worthiness of publication ”, “ so when I submitted for internal scrutiny, I was called by the co-ordinator who simply said there is nothing wrong with this study, but one important name is missing in authors’ list ” (indirectly requesting her name to be included). Likewise, another PI said, “ it is an unwritten institutional policy to include at least one professor on every publication ”. Yet another PI claimed, “ this is common in my laboratory – all post-doctoral scientists would have a chance to be an author ” “ by this way we would build their research esteem ”. His justification for this was “ many post-doctoral scientists spend a substantial amount of time mentoring other scientists and PhD students, therefore they deserve honorary authorships ”. Similar malpractices have also been highlighted by other authors (Vera-Badillo et al. 2016 ; Gøtzsche et al. 2007 ) but the worrying finding is that in many cases, the practice is institutionalised. With regards to authorships, according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE – www6 n.d. ), authorships can only be given to those with (a) a substantial contribution (at least to a significant part of the investigation), (b) involvement in manuscript preparation including contribution to critical review. However, our discussions have revealed complementary authorships, authorship denial, etc.

Malpractices in peer-review process

The final QRP highlighted by our interviewees relates to the vreviewing process. One academic openly admitted, “ I and Dr X usually use each other as reviewers because we both understand our research”, he further added, “the blind reviewing is the thing of the past, every author has his own writing style, and if you are in one particular research field, with time, you would be able to predict the origin of the manuscript you are reviewing (whether it is your friend or a person with a conflicting research interest!”. Another academic said that “ the era of blind reviewing is long gone, authors are intentionally or unintentionally identifying themselves within the manuscripts with sentences such as ‘previously we have shown’. “This allows the reviewer to identify the authors from the reference list ”. He further claimed he also experienced reviewers intentionally delaying acceptance or asking for further experiments to be carried out, simply because they wanted their manuscript (on a related topic) to be published first! Incidences like this, though minimal, cast questions on the reviewing process itself.

Recent reports by Thomas ( 2018 ) and Preston ( 2017 ) (see also Adler and Stayer 2017 ) have highlighted issues (or scams) such as an author reviewing his own manuscripts! Of course, many journals do not use the suggested reviewers; instead, they build a database of reviewers and randomly select appropriate reviewers. Still, it is not clear how robust this approach is in curtailing reviewer-based misconduct. Organisations such as Retraction Watch constantly pick up and report these malpractices, yet there are no definite sanctions or punishment for the culprits (Zimmerman 2017 )

One of the academic interviewees recalled an incidence in which an author has been dismissed due to a serious image manipulation scam, yet obtained a research tenure in another institution within 3 months of dismissal. Galbraith ( 2017 ) reviewed summaries of 284 integrity-related cases published by the Office of Research Integrity (ORI), and found that in around 47% of cases the researchers received moderate punishment and were often permitted to continue their research. This highlights the need for a globalised approach with clear sanction measures to tackle research misconduct. Although this is a small-scale study, it has highlighted that despite measures taken by research regulatory bodies, the problem of misconduct is still there. The main problem behind this is “the lack of care” underpinned by pressures for esteem.

Limitations

This is an exploratory study with minimal focus on standardisation, using details of qualitative approach and paradigm, or the impact of researcher characteristics and reflexivity. Therefore, the level of data presented herein is not suited for a full thematic analysis. Also, this is a small-scale study with a sample size of of 110 participants who are further divided into sub-groups (such as PhD students, technicians and PIs). This limits the scope of analysing variability in the responses of individual sub-groups, and therefore might have resulted in voluntary response bias (i.e. responses are influenced by individual perceptions against research misconduct). Yet, the study has highlighted the issue of research misconduct is worth pursuing using a large sample. It also highlighted the common QRPs (both laboratory and publication related) that need to be focussed further, enabling us to establish a right research design for future studies.

The way forward

This exploratory study (and previously reported large scale studies) showed QRP is still a problem in science and medical research. So what are the way forward to stop these types of misconduct? Whilst it is important to set up confirmed criteria for individual research conduct, it is also important to set up institutional policies. These policies should aim at promoting academic/research integrity, with paramount attention on the training of young researchers about research integrity. The focus should be on young researchers attaining rigorous learning/application of the best methodological and professional standards in their research. In fact, the Singapore statement on research integrity (www7 n.d. ), not only highlights the importance of individual researchers maintaining integrity in their research, but also insists the roles of institutions creating/sustaining research integrity via educational programmes with continuous monitoring (Cosentino and Picozzi 2013 ). Considering the findings from this study, it would also be appropriate to suggest an international regulatory body to regularly monitor these practices involving all stakeholders including governments.

In fact, this (and other studies) have highlighted the importance of re-validating the “voluntary commitment” to follow the research integrity. With respect to individual researchers, we propose using a unified approach for early career researchers (ECRs). They should be educated about the importance of ethics/ethical behaviours (see Table 3 ) for our suggestion for ECRs). We feel it is vital to provide compulsory ethical training throughout their career (not just at the beginning). It is also advisable to regularly carry out “peer review” visits/processes between laboratories for ethical and health/safety aspects. Most importantly, it is time for the research community to move away from the expectation of “self-governance” establish and international research governance guidelines that can monitored by individual countries.

We, do agree this is a small-scale pilot study and due to the way it was conducted, we are unable to carry out a full thematic analysis. This was mainly because the participants were extremely reluctant to offer information to formulate researcher characteristics. Also, the study data in many cases conforms to the previously reported fact, that QRP and research misconduct is still a problem within science and medicine. Yet, this study has attempted to narrate the previously unreported justifications given by the interviewees. In addition, we were able to highlight that these activities are becoming regular occurrence (those nick-named behaviours). We also provided some directives on how academic pressures are inflicted upon early career researchers. We also provided some recommendations in regard to the training ECRs.

Significance

The study has highlighted the negative influence on supervisory/peer pressures and/or inappropriate training may be main causes for these misconducts, highlighting the importance on devising and implementing a universal research code of conduct. Although this was an exploratory investigation, the data presented herein have pointed out that unethical practices can still be widespread within biomedical field. It highlighted the fact that despite the proactive/reflective measures taken by the research governance organisations, these practices are still going on in different countries within Europe. As the study being explorative, we had the flexibility to adapt and evolve our questions in reflection to the responses. This would help us to carry out a detailed systematic research in this topic involving international audience/researchers.

Concluding remarks

To summarise, this small-scale interview-based narrative study has highlighted that QRP and research misconduct is still a problem within science and medicine. Although they may be influenced by institutional and career-related pressures, these practices seriously undermine ethical standards, and question the validity of data that are being reported. The findings also suggest that both methodological and publication-related malpractices continue, despite being widely reported. The measures taken by journal editors and other regulatory bodies such as WAME and ICMJE may not be efficient to curtail these practices. Therefore, it would be important to take steps in providing a universal research code of conduct. Without a globalised approach with clear punitive measures for offenders, research misconduct and QRP not only affect reliability, reproducibility, and integrity of research, but also hinder the public trustworthiness for medical research. This study has also highlighted the importance of carrying out large-scale studies to obtain a clear picture about misconduct undermining research ethics culture.

Availability of data and materials

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article

Adler AC, Stayer SA (2017) Bias Among Peer Reviewers. JAMA. 318(8):755. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.9186

Article Google Scholar

Altman, LK (2006). For science gatekeepers, a credibility gap. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/02/health/02docs.html?pagewanted=all . Accessed 26 July 2019

Bero L (2017) Addressing Bias and Conflict of Interest Among Biomedical Researchers. JAMA 317(17):1723–1724. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.3854

Bik EM, Fang FC, Kullas AL, Davis RJ, Casadevall A (2018) Analysis and Correction of Inappropriate Image Duplication: the. Mol Cell Biol Exp. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00309-18

Blatt M (2013) Manipulation and Misconduct in the Handling of Image Data. Plant Physiol 163(1):3–4. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.900471

Bornmann L (2013) Research Misconduct—Definitions, Manifestations and Extent. Publications. 1:87–98. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications1030087

Bouter LM, Hendrix S (2017) Both whistle-blowers and the scientists they accuse are vulnerable and deserve protection. Account Res 24(6):359–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2017.1327814

Brainard J (2018) Rethinking retractions. Science. 362(6413):390–393. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.362.6413.390

Brall C, Maeckelberghe E, Porz R, Makhoul J, Schröder-Bäck P (2017) Research Ethics 2.0: New Perspectives on norms, values, and integrity in genomic research in times of even ccarcer resources. Public Health Genomics 20:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000462960

Buljan I, Barać L, Marušić A (2018) How researchers perceive research misconduct in biomedicine and how they would prevent it: A qualitative study in a small scientific community. Account Res 25(4):220–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2018.1463162

Collins FS and Tabak LA (2014) Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. NATURE (Comment) - https://www.nature.com/news/policy-nih-plans-to-enhance-reproducibility-1.14586

Cosentino M , and Picozzi M (2013) Transparency for each research article: Institutions must also be accountable for research integrity. BMJ 2013;347:f5477 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5477 .

Directive 2004/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 February 2004 on the inspection and verification of good laboratory practice (GLP). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2004:050:0028:0043:EN:PDF . Accessed 07 Sep 2019

Eaton SE, Chibry N, Toye MA, Toye MA, Rossi S (2019) Interinstitutional perspectives on contract cheating: a qualitative narrative exploration from Canada. Int J Educ Integr 15:9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-019-0046-0

Edwards M, Roy (2017) Academic Research in the 21st Century: Maintaining Scientific Integrity in a Climate of Perverse Incentives and Hypercompetition. Environ Eng Sci 34(1):51–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2016.0223

Fanelli D (2009) How Many Scientists Fabricate and Falsify Research? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Survey Data. Plos One 4(5):e5738

Fanelli D (2010) Do Pressures to Publish Increase Scientists' Bias? An Empirical Support from US States Data. PLoS One 5(4):e10271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010271

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A (2012) Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. PNAS 109(42):17028–11703. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109

Ferguson C, Marcus A, Oransky I (2014) Publishing: Publishing: The peer-review scam. Nature (News review). 515(7528):480-2. http://www.nature.com/news/publishing-the-peer-review-scam-1.16400. Accessed 21 Nov 2019

Galbraith KL (2017) Life after research misconduct: Punishments and the pursuit of second chances. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 12(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264616682568

Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen HK, HaahrMT ADG, Chan A-W (2007) Ghost Authorship in Industry-Initiated Randomised Trial. Plos-Med. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040019

Hevner AR (2007) A Three Cycle View of Design Science Research. Scand J Inf Syst 19(2):4 https://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol19/iss2/4

Google Scholar

Jenn NC (2006) Common Ethical Issues In Research And Publication. Malays Fam Physician 1(2-3):74–76

John LK, Loewenstein G, Prelec D (2012) Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol Sci. 23(5):524–532

Kornfeld DS, Titus SL (2016) (2016) Stop ignoring misconduct. Nature. 537(7618):29–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/537029a

Meadows, A. (2017). What does transparent peer review mean and why is it important? The Scholarly Kitchen, [blog of the Society for Scholarly Publishing.] [Google Scholar]

Ploug TJ (2018) Should all medical research be published? The moral responsibility of medical journal. Med Ethics 44:690–694

Preston A (2017) The future of peer review. Scie Am. Retrieved from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-future-of-peer-review/

Rawat S, Meena S (2014) Publish or perish: Where are we heading? J Res Med Sci. 19(2):87–89

Resnik DB, Shamoo AE (2017) Reproducibility and Research Integrity. Account Res. 24(2):116–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2016.1257387

Satalka P, Shaw D (2019) How do researchers acquire and develop notions of research integrity? A qualitative study among biomedical researchers in Switzerland. BMC Med Ethics 20:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0410-x

Shamoo AE (2016) Audit of research data. Account Res. 23(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2015.1096727

Thomas SP (2018) Current controversies regarding peer review in scholarly journals. Issues Ment Health Nurs 39(2):99–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1431443.

Tijdink JK, Bouter LM, Veldkamp CL, van de Ven PM, Wicherts JM, Smulders YM (2016) Personality traits are associated with research misbehavior in Dutch scientists: A cross-sectional study. Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163251

Titus SL, Wells JA, Rhoades LJ (2008) Repairing research integrity. Nature 453:980–982

Vera-Badillo, Marc Napoleonea FE, Krzyzanowskaa MK, Alibhaib SMH, Chanc A-W, Ocanad A, Templetone AJ, Serugaf B, Amira E, Tannocka IF, (2016) Honorary and ghost authorship in reports of randomised clinical trials in oncology. Eur J Cancer (66)1 doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.023

Verhagen H, Aruoma OI, van Delft JH, Dragsted LO, Ferguson LR, Knasmüller S, Pool-Zobel BL, Poulsen HE, Williamson G, Yannai S (2003) The 10 basic requirements for a scientific paper reporting antioxidant, antimutagenic or anticarcinogenic potential of test substances in in vitro experiments and animal studies in vivo. Food Chem Toxicol. 41(5):603–610

www1 n.d.: https://retractionwatch.com/the-center-for-scientific-integrity/ . Accessed 13 Nov 2019

www2 n.d.: http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html . Accessed 07 July 2019

www3 n.d.: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/12/e024499/DC1/embed/inline-supplementary-material-1.pdf?download=true . Accessed 26 July 2019

www4n.d.: http://www.crn.nihr.ac.uk/learning-development/ - National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN) - Accessed 13 Nov 2019

www5 n.d.: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors/forms-policies-and-checklists/scientific-misconduct . Accessed 07 July 2019

www6 n.d.: http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html - Accessed 0 July 2019

www7 n.d.: http://www.singaporestatement.org . Accessed 10 Aug 2019

Zimmerman SV (2017), "The Canadian Experience: A Response to ‘Developing Standards for Research Practice: Some Issues for Consideration’ by James Parry", Finding Common Ground: Consensus in Research Ethics Across the Social Sciences (Advances in Research Ethics and Integrity, Vol. 1) Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 103-109. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2398-601820170000001009

Download references

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank the organising committee of the 5th international conference named plagiarism across Europe and beyond, in Vilnius, Lithuania for accepting this paper to be presented in the conference. We also sincerely thank Dr Carol Stalker, school of Psychology, University of Derby, for her critical advice on the statistical analysis.

Not applicable – the study was carried out as a collaborative effort amongst the authors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Human Sciences, University of Derby, Derby, DE22 1GB, UK

S. D. Sivasubramaniam

Center of Research in Medical Pharmacology, University of Insubria, Via Ravasi, 2, 21100, Varese, VA, Italy

M. Cosentino & F. Marino

Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Dr Sivasubramaniam has produced the questionnaire with interview format with the contribution of all other authors. He also has read the manuscript with the help of Prof Consentino. The latter also contributed for the initial literature survey and discussion. Drs Marino and Ribario have helped in the data collection and analysis. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to S. D. Sivasubramaniam .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors can certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interests (including personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sivasubramaniam, S.D., Cosentino, M., Ribeiro, L. et al. Unethical practices within medical research and publication – An exploratory study. Int J Educ Integr 17 , 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00072-y

Download citation

Received : 17 July 2020

Accepted : 24 January 2021

Published : 01 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00072-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical research

- Research misconduct

- Committed bias

- Unethical practices

International Journal for Educational Integrity

ISSN: 1833-2595

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Social Work: Academic Integrity

Academic integrity.

- Examples of Unethical Behavior

- Citing Your Work Using APA Style

One of the best ways to be an ethical researcher is to choose to act in honest ways. However, it can sometimes be difficult to know whether or not you might unintentionally be doing something unethical. This page will help you to identify specific types of academic misconduct and give you tips on how to be an ethical researcher.

Types of Misconduct

There are many different ways someone might act in a way that is unethical in the research process. Academic integrity isn't about just avoiding cheating or choosing not to plagiarize, it's about understanding how to give credit where it's deserved and ethically building on ideas of previous researchers.

Listed below are just some examples of the most common types of academic misconduct. Although students sometimes might unknowingly plagiarized, or fail to cite something properly, the key to avoiding intentional or unintentional misconduct is to identify opportunities to act ethically.

Examples of Cheating

Cheating is committing fraud and/or deception on a record, report, paper, computer assignment, examiniation, or any other course or field placement assignment. Examples of cheating include:

- Obtaining work or information from someone else and submitting it under one's own name.

- Using unauthorized notes, or study aids, or information from another student or student's paper on an examination.

- Communicating answers with another person during an exam.

- Altering graded work after it has been returned, and then submitting the work for regrading without the instructor's knowledge.

- Allowing another person to do one's work and submitting it under one's own name.

- Preprogramming a calculator to contain answers or other unauthorized information for exams.

- Submitting substantially the same paper for two or more classes in the same or different terms without the expressed approval of each instructor.

- Taking an exam for another person or having someone take an exam for you.

- Fabricating data which were not gathered in accordance with the appropriate methods for collecting or generating data and failing to include a substantially accurate account of the method by which the data were gathered or collected.

How to Avoid Cheating

Cheating is often one of the easier types of misconduct to avoid because you can usually consciously choose not to cheat. Some ways you can avoid cheating are by:

Giving yourself enough time to prepare for a test or quiz.

Keeping your eyes on your own work while in-class and not helping others to cheat.

Creating original work for each assignment and not reusing papers and work from other classes.

- Taking the time needed to create an accurate bibliography for your paper.

Examples of Plagiarism

Plagiarism is representing someone else's ideas, words, statements, or other work as one's own without proper acknowledgement or citation. Plagiarism can happen intentionally or unintentionally so it's good to know how to recognize what constitutes plagiarism. Some examples of plagiarism include:

- Copying word for word or lifting phrases or a unique word from a source or reference, whether oral, printed, or on the internet, without proper attribution

- Paraphrasing, that is, using another person's written words or ideas, albeit in one's own words, as if they were one's own thoughts.

- Borrowing facts, statistics, graphs, or other illustrative material without proper reference, unless the information is common knowledge, in common public use.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

The key to avoiding plagiarism is to give credit where credit is due. Some ways to not plagiarize include:

- Taking good notes as you read. Note the author and page number of where you read ideas and/or facts.

- Including quotation marks in your notes if you copy exact original wording.

- Using a good system of organizing your research notes. Make time to provide citations in your paper.

- Making sure to use in-text citations to give authors credit for their ideas. Even if you change the wording or paraphrase text in your paper, if it's not something that's common knowledge it should be cited.

- Checking with your professor, or a librarian if you're not sure if something is common knowledge and doesn't need a citation.

Falsification of Data, Records, and Official Documents

Falsification of data, records, and/or official documents.

Academic integrity isn't just about the words and ideas that you present. It's also about the data you use, and the documents which relate to you throughout your professional life. Here are some examples of what it means to falsify information:

- Fabrication of data

- Altering documents affecting academic records

- Misrepresentation of academic status or degrees earned

- Forging a signature of authorization or falsifying information on an official document, grade report, letter of recommendation/reference, letter of permission, petition, or any other official or unofficial document

Unacceptable Collaboration

You will often be asked to work with others as a part of your School of Social Work assignments, so it can become common place to think that all work can be collaborative. The truth is that collaboration is sometimes unacceptable when a student works with another or others on a project and then submits written work which is represented explicitly or implicitly as the student's own work.

Equally unacceptable is submitting a group project in which you did little or none of the work yet you take the credit for the work done by others within your group.

- << Previous: Academic Integrity

- Next: Citing Your Work Using APA Style >>

Ethical Action in Global Research

Case examples.

- Global Research

- Ethical Stories

In reviewing case studies and examples brought to our workshops by researchers, it is clear that:

Ethical issues in global research are extremely complex.

Solutions are rarely simple or perfect. They need to be contextually relevant if they are to work.

It may be that a ‘fully worked’ solution is not clear but that parts of the solution will give enough traction to begin a process of resolution.

Different individuals and different groups often come to different conclusions. Both may follow a principled stance but make different justifiable choices at a number of decision-making points. Some solutions might be a better fit for different research teams, depending on the skills and expertise of each member.

Ethical decision making is more than following a set of rules. It should be about being open to exploring a range of possibilities, each of which may be ethical but may have different implications and may have different pragmatic constraints.

Ethical issues emerge across all stages of the research journey and may change over time.

Helpful questions in finding a solution include:

- What might have pre-empted the issue (this is relevant to future proofing)?

- What were the early warning signs?

- How could key issues be assessed once they have arisen?

- What should be the immediate response?

- What should be the follow-up response at each subsequent stage of the research journey?

Case Analysis Template

We have developed a template to help your team analyse ethical conflicts and look for solutions. This template highlights the importance of considering all phases of the research journey. It also highlights the importance of considering Place, People, Principles and Precedent both in the analysis and in the search for solutions.

Please see the case examples below. We do not claim that these examples are applicable to different contexts. We know that ethical conflicts need to be analyzed according to their own context. What works in one place can be disastrous in another.

Case Study 1

- Read more about Case Study 1

Case Study 2 and 3 (Paper: COVID-19)

In this paper we offered two case analyses to exemplify the utility of the toolkit as a flexible and dynamic tool to promote ethical research in the context of COVID-19.

The paper was published as: Clara Calia , Corinne Reid , Cristóbal Guerra , Abdul-Gafar Oshodi , Charles Marley , Action Amos , Paulina Barrera & Liz Grant (2020): Ethical challenges in the COVID-19 research context: a toolkit for supporting analysis and resolution, Ethics & Behavior, DOI: 10.1080/10508422.2020.1800469

- Read more about Case Study 2 and 3 (Paper: COVID-19)

Case Study 4: Facing an ethical breach

- Read more about Case Study 4: Facing an ethical breach

Case Study 5: Protecting vulnerable groups (in English and Spanish)

Case 5 (en Español) Case 5

- Read more about Case Study 5: Protecting vulnerable groups (in English and Spanish)

Case Study 6: Data interpretation and consent

- Read more about Case Study 6: Data interpretation and consent

Case Study 7: Consent

- Read more about Case Study 7: Consent

Case Study 8: Research project development and engaging communities

- Read more about Case Study 8: Research project development and engaging communities

Share this page

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Unethical Behaviors of Authors Who Published Papers in the Biomedical Journals Became a Global Problem

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author: Prof. Izet Masic, MD, PhD, FWAAS, FIAHSI, FEFMI, FACMI. Academy of Medical Sciences of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Email: [email protected] ORCID ID: http//www.orcid.org/0000-0000-2-9080-5456

Received 2020 Jan 12; Accepted 2020 Feb 12.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

1. INTRODUCTION

Committee of Publishing Ethics (COPE) announced great problem with retraction of the papers published in journals which are cited in Web of Science data base, before and after retractions from the journals were papers published, because of unethical behaviours of the authors - https://retractionwatch.com/the-retraction-watch-leaderboard/top-10-most-highly-cited-retracted-papers/ ( 1 ).

In the text “Top 10 most highly cited retracted papers” is written “Ever curious which retracted papers have been most cited by other scientists? Below, we present the list of the 10 most highly cited retractions as of May 2019. Readers will see some familiar entries, such as the infamous Lancet paper by Andrew Wakefield that originally suggested a link between autism and childhood vaccines ( 1 ). You’ll note that many papers - including the 2 most cited paper - received more citations after they were retracted, which research has shown is an ongoing problem”. Although just missing out on the top ten and coming in at number 11 – with 670 citing articles - this article was previously designated as a “Highly Cited Paper” by Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science, meaning it was ranked in the top one percent of all papers in its subject field in the last 10 years ( 1 ). That fact is impressive.

Also, in our journal Jankovic S. et al. published paper about most frequent mistakes regarding used methodology and statistical analysis of the presentation of final results of the investigation, randomly taken from 43 journals cited in Web of Science. The authors found that basic principles of design (local control, randomization and replicaion ) were completely implemented in only 7% of analyzed studies. Exactly the same result was reached when the same authors analyzed studies published in medical journals edited in Bosnia and Herzegovina ( 2 ).

Third important fact to be mentioned in this Editorial is about conclusions of presenters (Editors of medical journals from former Yugoslavia countries) at Scientific Conference “SWEP 2018” named „Ethical Dilemmas in Science Editing and Publishing”, organized in Sarajevo, during scientific meeting “Days of AMNuBiH 2018”, by saying that the advent of unethical behaviors in the academic community became an international problem ( 3 , 4 ).

That problem became more and more interest of the Committee of Publishing Ethics (COPE), International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), European Association of Science Editing (EASE), etc., when trying to establish certain rules and standards to detect plagiarism and other types of unethical behaviors in scientific research and publications and to avoid and sanction it ( 5 - 8 ).

Scientific and academic community in Bosnia and Herzegovina after wartime in our country and also after accepting Bologna concept of education at our universities is in a major crisis when this is a problem. Text by Danijel Hadzovic „Sarajevo students and professors in the network of plagiarism: how much the master thesis cost?” raised his attention and interest in this problem.

In the article, he writes: „Affairs in the plagiarism of graduate and master theses or doctoral dissertations, in which the main actors are politicians and other high public officials, are not have been particularly novel in this area for long time. Nevertheless, the issue seemed to have taken on a massive dimension and became a new popular business activity ( 9 ).

It’s enough just to search „making theses“ on Facebook and you will find literally dozens of pages that offer the services of writing graduation, seminar, and even master papers. Probably the most sophisticated site for such services is maturskiradovi.net. It is located in Serbia, but offers services in Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, Hungarian, Macedonian and English”...

In a country where today almost every municipality has at least one faculty, and diplomas are printed on a factory lane, it should not be over-whelmingly surprising that many students will decide to buy for the money other’s knowledge and present it as their own, to complete their faculty as soon as possible... The key question here is what competent institutions can do in dealing with this phenomenon that is getting more and more acute ( 9 ).

2. EXAMPLES OF UNETHICAL BEHAVIORS IN THE “MEDICAL ARCHIVES” JOURNAL

The unethical behaviors of the authors who want to publish their papers in our journal(s) always occur because they do not know about so much information about COPE guidelines and rules. In Medical Arhives journal we “suffering” with a lot of cases of unethical behaviors long time, and some of extreme cases of plagiarsim and other unethical behaviours we already written in the past. Some of them we deposited on our web site: www.medarch.org making visible for academic community and as a measure to prevent cases in the future.

During submission of the papers on web site of the journal authors must submitt also forms of Copyright Assignement Form and Author’s Contribution Form signed by ALL AUTHORS, as statment that they have read (final proof reading) formatted PDF of their paper and agreed with all conditions written in attached documents.

Because, prior to submission, we always declare “I/We hereby confirm that the manuscript has no actual or potential conflict of interest with any party, including but not limited to any financial, personal or other relationship with other people or organization within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence. We confirm that the paper has not been published previously, is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, and is not being simultaneously submitted elsewhere”.

Unfortunately, authors did not follow mentioned instructions, and it is very severe mistake which will make confused for any journals they submitted.

Editors cocluded at SWEP 2018 Conference that warning letter should be issued out along with announcement on the unethical behavior as a part to remind all of authors they need to know prior to submission ( 3 ).

Also, Editors need to announce to the authors of the papers about Plagiarism, as COPE to avoid any case like and propose to sanctioned it puting their names and affiliations on the “black list” ( 10 - 14 ). Because if journal(s) published paper(s), and later retract that paper from the issue, it will harm reputation of both journal and authors ( 15 -18).

“All submissions are screened by a similarity detection software (iThenticate by CrossCheck). Manuscripts with an overall similarity index of greater than 20%, or duplication rate at or higher than 5% with a single source are returned back to authors without further evaluation along with the similarity report.

In the event of alleged or suspected research misconduct, e.g., plagiarism, citation manipulation, and data falsification/fabrication, the Editorial Board will follow and act in accordance with COPE guidelines” ( 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 )

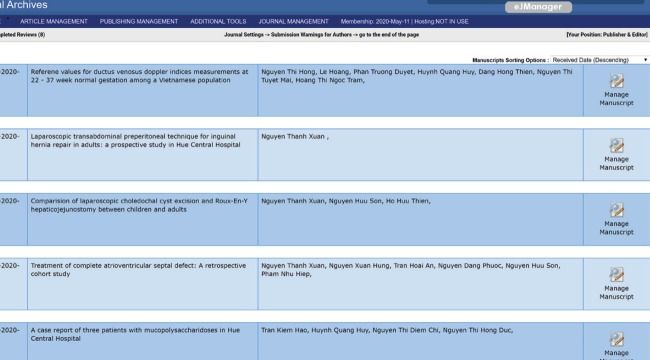

In the next part of this Editorial we will show as example our data base www.scopemed.org - our DBMS an example of several papers submitted by Vietnamese authors this month, which we founded as duple or triple submited in our and other journals ( Figures 1 and 2 ).

Figure 1. Screen Shot of List of Authors from Vietnam who submitted their papers in Medical Archives journal in 2020.

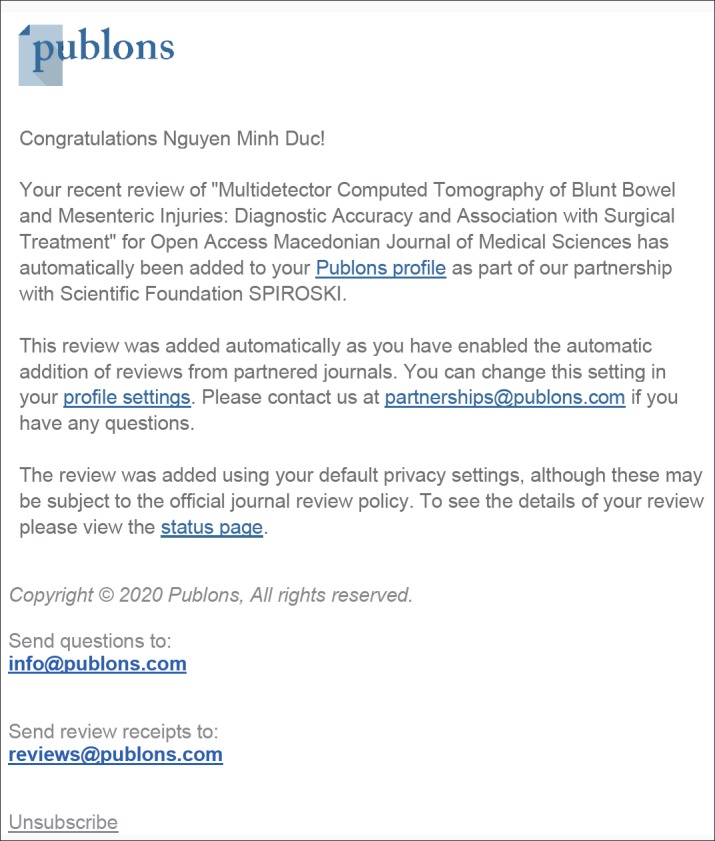

Figure 2. Screenshot of confirmation from OAMJMS about papers review of Vietnamese authors .

The first example (attached letter from reviewer):

Dear Prof Izet Masic,

There is one paper “ Multidetector Computed Tomography of Blunt Bowel and Mesenteric Injuries: Diagnostic Accuracy and Association with Surgical Treatment “ submitted both in Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Science and Medical Archives simultaneously. I am incidentally as reviewer of both journals and same manuscript, therefore, I reject it immediately to avoid double publications.

If authors continue double submissions from 2 or more journals, EIC and All EDITORs please follow COPE guidelines to ban authors from further submissions.

Kind regards

Dear N. M. D.,

We are inviting you to review the manuscript titled as (Multidetector Computed Tomography of Blunt Bowel and Mesenteric Injuries: Diagnostic Accuracy and Association with Surgical Treatment) that was sent for possible publication in Medical Archives. You could accept or reject this offer by clicking the appropriate link below.

If you accept reviewing, we will send your login information in following email.

You should answer this message by clicking one of the option links below in 7 days.

Accept : http://www.ejmanager.com/reviewers/index.php?ro=a&de=1583066159&mn=84647

Reject : http://www.ejmanager.com/reviewers/index.php?ro=r&de=1583066159&mn=84647

Sincerely yours,

Medical Archives

http://my.ejmanager.com/medarh

http://www.medarch.org/

Objectives: The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of computed-tomography (CT) findings in the diagnosis of bowel and mesenteric injuries, the association between these findings, and treatment strategy.

Methods: From June 2018 to July 2019, 86 patients that had 16-section multidetector CT diagnosis of blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries and had undergone laparotomy were reviewed. Two abdominal radiologists independently interpreted CT scans, and recorded mesenteric and bowel signs that referred to blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries. CT accuracy in the diagnosis of bowel and mesenteric injuries was determined with laparotomy findings that were considered as a gold standard. The association between CT findings and treatment strategy was quantified by an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) OR. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results: Bowel-wall rupture, active extravasation, and reduced bowel-wall enhancement were findings that had a high specificity of 100%, 98.15%, and 100%, respectively. Pneumoperitoneum had the highest sensitivity of 83.33%. Bowel-wall rupture, Janus signs, pneumoperitoneum, and mesenteric stranding were significant correlations with surgical treatment. The presence of these findings increased the possibility of implementing surgical treatment seven-, six-, 29-, and threefold, respectively. Interobserver agreement was very good for bowel-wall rupture, active extravasation, bowel hematoma, and pneumoperitoneum.

Conclusions: Bowel-wall rupture was the definite sign of bowel injury and it had significant correlation with surgical treatment. Pneumoperitoneum was an unspecific sign of blunt bowel injury; however, immediate surgery should be considered when this is found.

Reviewer N. M. D.

Dear Editor in Chief

I doubted that all these submissions are double from OPEN ACCESS MACEDONIAN JOURNAL of MEDICAL SCIENCE or elsewhere and under consideration of 2 or more publishers. I have asked them but they did not tell me what they did and some disclose double submissions. I believe that we can not perform review because of wasting time and avoiding double publications. Please announce to other reviewers immediately to help them save time and mind.

Reviewer N.M. D.

Dear Prof Izet Masic

They violated severely Cope guidelines and performed dangerously task to improve the chance of publications! I have asked some of them, unfortunately, they submitted twice elsewhere, even three journals immediately! I think that rejection will save time for all editors, reviewers and publisher. Reputation will be cured at least for authors and journals. Maybe next time, they will know that all: Publisher, Editor-in-Cchief are very rigorous, balance and strict. Finaly, why Scopemed does not perform Ithenciate at least twice per manuscript? Why this happen! I think about the high plagiarism % which a severe but common problem!

3. DISCUSSION

Generally, unethical behavior in biomedical research is any significant mistreatment of intellectual property or participation of other parties, deliberately obstructing the process of investigation or distortion of scientific evidence, as well as all the behavior that affect the integrity of scientific practice ( 3 , 5 , 6 - 11 ). In 2000 the United States defined the unethical conduct in scientific research as fabrication, falsifying and plagiarism in the process of proposing, conducting and publishing the results ( 12 - 15 ).

Studies show that the unethical conduct is directly related to the following factors: a) Increased academic expectations and a greater desire for publishing papers; b) Personal ambition, vanity and desire for fame; c) Laziness; d) Greed, which is directly linked to the financial gain; e) Lack the moral capacity to distinguish right from wrong. In a broad sense, the author is any person who had significant intellectual contribution to a particular study. The International Comitee of Medical Journal Editors ICMJE as recognized organization dealing with ethical issues in biomedical research, defines authorship follows: a) Significant contribution to the concept, design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the study; b) Writing study template, or revision in terms of intellectual content; c) Final approval of the version to publication. The author needs to meet all three ( 5 ).

Every scientist has its own vision of what it takes to become the author. But often, among the authors of a project this visions are different. Personal conflicts and turmoil can often lead to disagreements on the issue of to whom belongs the authorship ( 5 ). It is defined as a publication of an article which is identical or largely. It is defined as a publication of an article which is identical or largely overlaps with the article already published with or without acknowledgment: a) Two articles share the same hypothesis, results and conclusions; b) The authors are trying to reach the readers who may not be familiar with; c) already published article, especially if it is in another language, such as Chinese, Vietnamese, Arabic, Turkish, Albanian, Macedonian, etc. ( 5 , 6 , 10 )

Duplicate publication is considered unethical for several reasons. a) The first is that in an inadequate way attempts to increase the scope of their own published works, other important, is that the article has the potential to change the image of documents; b) For example, if the results were taken into account two or more times in a meta-analysis, the results would not be valid; c) A study was conducted of all published papers in which was investigated the effect of the drug on postoperative vomiting ( 5 , 16 ). It was observed that 17% of published papers was duplicates, in which 28% of patient data was a duplicate. This has led to a situation in which the efficacy of this drug was increased by 23% ( 5 , 15 ). This example points out the danger of duplication of publications by scientists who have conducted research, especially when making conclusions about the efficacy and safety of a drug. Good practice in publishing an article requires that authors can submit drafts of their work only to one journal at a given moment. Regardless of this, still duplicate papers occurs and as such continues to be significant problem across scientific journals ( 15 , 16 ).

4. CONCLUSION

Unethical behaviours, especialy plagiarism in scientific publishing is an almost unsolvable problem, and the greatest responsibility have editors of the journals and reviewers of the papers with which the authors apply to journals for their publication. ICT and various software packages help to detect plagiarism and other form of unethical behaviors of authors of the papers and other scientific publications, but for journals that publish works in local languages, solutions are still missing. Following this introductory word, followed the lectures which presented the above-mentioned problems from different aspects and in different fields of biomedical sciences.

Author’s contribution

Author was included in all phases of preparation of this article and made final proof reading before printing.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial support and sponsorship

- 1. [February 15th, 2020]. https://retractionwatch.com/the-retraction-watch-leaderboard/top-10-most-highly-cited-retracted-papers/

- 2. Jankovic SM, Kapo B, Sukalo A, Masic I. Evaluation of Published Preclinical Experimental Studies in Medicine: Methodology Issues. Med Arch. 2019 Oct;73(5):298–302. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2019.73.298-302. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Masic I, Jakovljevic M, Sinanovic O, Gajovic S, Spiroski M, Jusufovic R, et al. The Second Mediterranean Seminar on Science Writing, Editing and Publishing (SWEP - 2018), Sarajevo, December 8th, 2018. Acta Inform Med. 2018 Dec;26(4):284–299. doi: 10.5455/aim.2018.26.284-299. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Masic I, Jankovic SM, Begic E. PhD Students and the Most Frequent Mistakes During Data Interpretation by Statistical Analysis Software. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019 Jul 4;262:105–109. doi: 10.3233/SHTI190028. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Masic I, Kujundzic E. Science Editing in Biomedicine and Humanities. Avicena: 2013. p. 272. ISBN: 978-9958-720-49-9. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Shoja Mohammadali M, Arynchyna Anastasia., editors. A Guide to the Scientific Career. London: Willey Blackwell; 2019. pp. 163–178. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Masic I, Begic E, Donev MD, Gajovic S, Gasparyan YA, Jakovljevic M, Milosevic BD, Sinanovic O, Sokolovic S, Uzunovic S, Zerem E. Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility Of Scholarly Journals. Croat Med J. 2016;57:527–529. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2016.57.527.529. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Masic I, Donev D, Sinanovic O, Jakovljevic M, et al. The First Mediterranean Seminar on Science Writing, Editing and Publishing, Sarajevo, December 2-3, 2016. Acta Inform Med. 2016 Dec;24(6):424–435. doi: 10.5455/aim.2016.24.424-435. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. http://inforadar.ba/sarajevski-studenti-i-profe-sori-u-mrezi-plagijarizma-posto-magistarski/ . Retrieved on November 25th, 2018.

- 10. Masic I. Plagiarism in the Scientific Publishing. Acta Inform Med. 2012 Dec;20(4):208–213. doi: 10.5455/aim.2012.20.208-213. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Masic I, Hodzic A, Mulic S. Ethics in medical research and publication. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(9):1073–1082. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Jankovic S, Masic I. Evaluation of Preclinical and Clinical Studies Published in Medical Journals of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Methodology issues. Med Arch. 2020 Mar;28(1):4–11. doi: 10.5455/aim.2020.28.4-11. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Masic I, Sabzghabaee AM. How Clinicians can Validate Scientific Contents? Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2014 Jul;19(7):583–585. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Masic I. Ethics in Research and Publication of Research Articles. South Eastern Public Health Journal. 2014 Aug; doi: 10.12908/SEEJPH-2014-27. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Masic I. Medical Publication and Scientometrics. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2013 Jun;18(6):624–630. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Donev D. New developments in publishing related to authorship. Contributions. Sec of Med Sci. 2019;XL 3:151–159. Available at: http://manu.edu.mk/prilozi/40_3/16.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (510.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Research ethics.

Jennifer M. Barrow ; Grace D. Brannan ; Paras B. Khandhar .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Multiple examples of unethical research studies conducted in the past throughout the world have cast a significant historical shadow on research involving human subjects. Examples include the Tuskegee Syphilis Study from 1932 to 1972, Nazi medical experimentation in the 1930s and 1940s, and research conducted at the Willowbrook State School in the 1950s and 1960s. [1] As the aftermath of these practices, wherein uninformed and unaware patients were exposed to disease or subject to other unproven treatments, became known, the need for rules governing the design and implementation of human-subject research protocols became very evident.

The first such ethical code for research was the Nuremberg Code, arising in the aftermath of Nazi research atrocities brought to light in the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials. [1] This set of international research standards sought to prevent gross research misconduct and abuse of vulnerable and unwitting research subjects by establishing specific human subject protective factors. A direct descendant of this code was drafted in 1978 in the United States, known as the Belmont Report, and this legislation forms the backbone of regulation of clinical research in the USA since its adoption. [2] The Belmont Report contains 3 basic ethical principles:

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

Additionally, the Belmont Report details research-based protective applications for informed consent, risk/benefit assessment, and participant selection. [3]

- Issues of Concern

The first protective principle stemming from the 1978 Belmont Report is the principle of Respect for Persons, also known as human dignity. [2] This dictates researchers must work to protect research participants' autonomy while also ensuring full disclosure of factors surrounding the study, including potential harms and benefits. According to the Belmont Report, "an autonomous person is an individual capable of deliberation about personal goals and acting under the direction of such deliberation." [1]

To ensure participants have the autonomous right to self-determination, researchers must ensure that potential participants understand that they have the right to decide whether or not to participate in research studies voluntarily and that declining to participate in any research does not affect in any way their access to current or subsequent care. Also, self-determined participants must be able to ask the researcher questions and comprehend the questions asked by the researcher. Researchers must also inform participants that they may stop participating in the study without fear of penalty. [4] As noted in the Belmont Report definition above, not all individuals can be autonomous concerning research participation. Whether because of the individual's developmental level or because of various illnesses or disabilities, some individuals require special research protections that may involve exclusion from research activities that can cause potential harm or appointing a third-party guardian to oversee the participation of such vulnerable persons. [5]

Researchers must also ensure they do not coerce potential participants into agreeing to participate in studies. Coercion refers to threats of penalty, whether implied or explicit, if participants decline to participate or opt out of a study. Additionally, giving potential participants extreme rewards for agreeing to participate can be a form of coercion. The rewards may provide an enticing enough incentive that the participant feels they need to participate. In contrast, they would otherwise have declined if such a reward were not offered. While researchers often use various rewards and incentives in studies, they must carefully review this possibility of coercion. Some incentives may pressure potential participants into joining a study, thereby stripping participants of complete self-determination. [3]