- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.3: THE BIG PICTURE- Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 302676

- Timothy Krause

- Portland Community College via OpenOregon

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay — often called the five-paragraph essay — are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clear thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and connecting your main idea to the world through the introduction and conclusion.

In college, you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph essay by itself is bland and formulaic. In other words, it is not very interesting to read, and it doesn’t feel very natural. More importantly, it doesn’t get you (or your reader) to think very deeply. Your professors are looking for a more ambitious, arguable, and compelling thesis with real-life evidence for all key points — all in a more organic (less artificial) structure.

What does that look like?

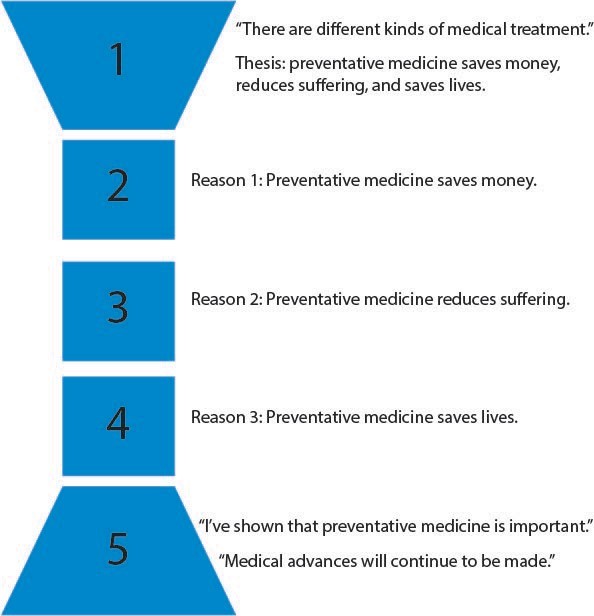

The five-paragraph essay, outlined below in Figure 3.1 is probably what you’re used to: the introduction starts general and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this format, the thesis uses that magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the conclusion restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers to organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

Figure 3.1 The traditional five-paragraph essay structure

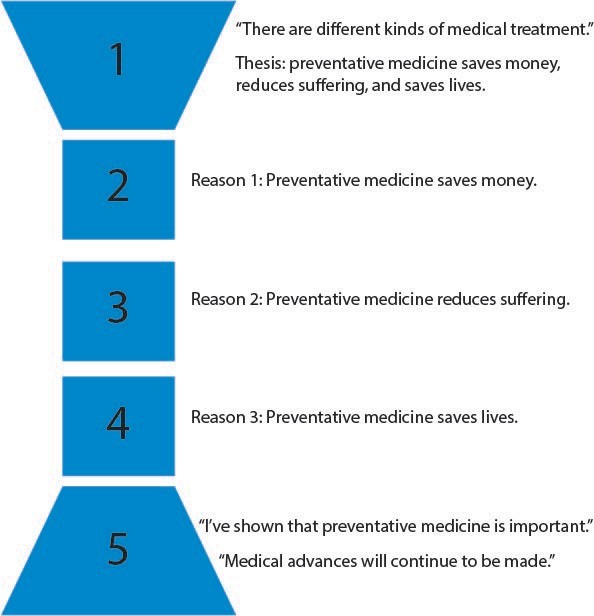

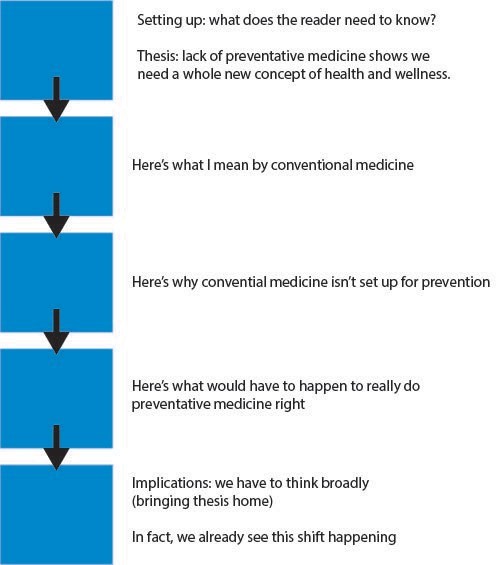

Figure 3.2, in contrast, represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form that is expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply presenting a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Hm. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on.

The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph essay (Figure 3.1), it probably is not important which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (Figure 3.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next. If you changed the order of the body paragraphs, then the essay would not make sense.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay has a thesis that does not have an obvious conclusion, the reader comes to the end of the essay thinking, “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, the author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

Figure 3.2 The organic research essay structure

All that time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was not wasted. There’s an idiom in English: You have to know the rules before you can break the rules. But now is the time to move beyond an obvious thesis, loosely related body paragraphs, and a repetitive conclusion. Now is the time for you to move beyond the five-paragraph essay.

Watch this video to learn more about moving beyond the five-paragraph essay to an organic research essay:

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://pb.libretexts.org/synthesis/?p=113

Now practice with this exercise; it is not graded, and you may repeat it as many times as you wish:

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.

Text adapted from: Guptill, Amy. Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence . 2022. Open SUNY Textbooks, 2016, milneopentextbooks.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/ . Accessed 16 Jan. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA

Video from: The Nature of Writing. “What’s Wrong with the Five Paragraph Essay and How to Write Organically (Animated Video).” Www.youtube.com, 3 Sept. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAlcAGVBEXU. Accessed 30 Dec. 2021.

1. Audience and Purpose

2. content and theme, 3. tone and mood, 4. stylistic devices, 5. structure / layout.

Context of composition

- Describe the time and place that this text was produced in.

- Who wrote the text?

- Why was the text produced? (purpose) What makes you say this?

Intended audience

- Who was this text aimed at? How can you tell?

Context of interpretation / reception

- What are your circumstances? (time and place)

- How do these factors influence your reading of the text?

Content is what is in a text. Themes are more what a text is about (big ideas).

- Describe what is going on in the text (key features).

- What is this text about?

- What is the author’s message?

- What is the significance of the text to its audience?

- What is the text actually saying?

Tone refers to the implied attitude of the author of a text and the ‘voice’ which shows this attitude. Mood refers more to the emotional atmosphere that is produced for a reader when experiencing a text.

- What is the writer’s tone?

- How does the author sound?

- What kind of diction does the author use to create this tone?

- How does the text make the reader feel? (mood)

- How does the diction contribute to this effect?

Style refers to the ‘how’ of a text - how do the writers say whatever it is that they say? (e.g. rhetorical devices, diction, figurative language, syntax etc…)

- What stylistic devices does the writer use? What effects do these devices have on a reader?

Structure refers to the form of a text.

- What kind of text is it? What features let you know this?

- What structural conventions for that text type are used?

- Does this text conform to, or deviate from, the standard conventions for that particular text type?

Social Media

2 A Review of Essays and Paragraphs

Learning Objectives

- Write a clear thesis statement that unifies your essay

- Organize sentences around a topic sentence in a body paragraph

- Create smooth transitions in a paragraph

Download and/or print this chapter: Reading, Thinking, and Writing for College – Ch. 2

Basic Essay Structure

Most likely, if you’re a first-semester college student, the last time you had to write an essay was in high school. High school essay writing typically emphasizes the five-paragraph essay: introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you’ve been out of high school for a while or if you struggled with essay writing in high school, this chapter will help you review this basic structure, which can serve as a foundation for your college-level essays.

The skills that go into the five-paragraph essay are indispensable. The outline below in Figure 3.1 is probably what you’ve been taught about essay structure. The introduction starts general and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this format, the thesis uses that magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the conclusion restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers to organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

Figure 3.1 The traditional five-paragraph essay structure

All that time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was not wasted. In a college-level writing class, though, you’ll be expected to move beyond this basic formula. The video below explains the basic five-paragraph essay structure and how you will be expected to develop a more sophisticated approach to writing for your college classes.

As the video explained, the body paragraphs in your essays are supposed to develop your thesis, and the thesis, as you may recall, is the “main idea” or “main claim” of your essay. For college-level writing, though, the thesis usually does more than simply announce the main idea of your essay. A good thesis is an original idea or opinion that you’ve developed by studying, reading, and thinking critically about your topic. A good thesis statement conveys your purpose for writing and previews what’s coming in your essay. In addition, a college-level thesis meets these criteria:

- A good thesis is non-obvious. High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide-enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough for high school! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious, more original, and more engaging. College instructors, on the other hand, always expect you to produce something more sophisticated and specific. They also want you to go beyond the obvious and offer your original thinking about a topic. To write a good thesis, therefore, most writers revise their thesis statements as they work on their essays. Writing about a topic helps them discover more interesting, specific points to make about the topic. A good thesis reflects good critical thinking and an original perspective.

- A good thesis is arguable . In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “controversial.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” doesn’t mean highly opinionated, and the goal of an academic essay isn’t necessarily to convert every reader to your way of thinking. Rather, a good thesis offers readers a new idea, a new perspective, or an opinion about a topic. The need to be arguable dovetails with the need to be specific: only when we have deeply explored a problem can we arrive at an original and specific argument that legitimately needs 3, 5, 10, or 20 pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper.

- A good thesis is specific . You don’t want to set too ambitious an agenda, though! Some student writers fear that they won’t have enough to write about if they present a specific thesis, so they attempt to cover too much. A thesis like “sustainability is important” may seem like a great thesis because one could write all of the reasons for why it’s important, but the vague language invites a superficial discussion of a complicated topic. A thesis like “sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” limits the scope of the discussion, which in turn means that the essay itself will provide a more in-depth discussion of sustainability policies. It could even be more specific: which sustainability policies?

How do you produce a thesis that meets these criteria? Many instructors and writers find useful a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. [1]

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight.

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then, with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings about its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not. In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together.

To outline this example:

- First story : Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story : While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story : Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis: [3]

- First story : Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story : However, in her work we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story : Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story : Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the U.S. of the light brown apple moth (LBAM) , an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story : Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story : Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Basic Paragraph Structure

Think back to when you first learned to write paragraphs. Maybe you learned that paragraphs are supposed to have a certain number of sentences, or maybe you learned an acronym for what a paragraph is, such as the P. I. E. paragraph format (P=point, I=information, E=explanation). Some students learn to write paragraphs that follow certain patterns, such as narrative or compare/contrast. Whatever you learned about paragraphs, you probably remember that paragraphs need to include a topic sentence, supporting information, smooth transitions from one sentence to the next, and a concluding sentence. Take a moment to review these elements of all paragraphs.

Topic Sentences

The main idea of the paragraph is stated in the topic sentence. A good topic sentence does the following:

- introduces the rest of the paragraph

- contains both a topic and an idea or opinion about that topic

- is clear and easy to follow

- does not include supporting details

- engages the reader

For example:

Development of the Alaska oil fields threaten the already-endangered Northern Sea Otters.

This sentence introduces the topic and the writer’s opinion. After reading this sentence, a reader might reasonably expect the writer to go on to provide supporting details and facts about what the threat is. The sentence is clear and the word choice is interesting.

Here is another example:

Many major league baseball players have cheated by “corking” their bats.

Again, the topic and opinion are clear and specific, the details (what is corking? which players?) are saved for later, and the word choice is powerful.

Now look at this example:

I think everyone should be able to take a pet, especially service pets, to work because they provide comfort, and the potential problems they might cause can be eliminated if companies develop good policies.

Even though the topic and opinion are evident, the sentence is not focused or specific. It’s not likely that the writer could provide enough support to argue that every place of employment, from McDonald’s to a law office, should allow any kind of pets, from service dogs to parakeets. Furthermore, the writer is also offering two points that need to be discussed: pets provide comfort and pets don’t cause problems. Most likely, each of these points needs to be addressed in a separate paragraph.

The writer could revise the topic sentence into two topic sentences:

- Being able to bring a dog or cat to the office can be comforting to people who work at a desk from 9:00-5:00.

- Specific policies and practices can eliminate some of the problems that might occur if employees are allowed to bring pets to the office.

These two paragraphs might appear in an essay arguing that people should be able to take their pets in public more often. The topic sentence would clearly support such a thesis, which would need many more paragraphs of support.

Typically, you should place the topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph. In college and business writing, readers often lose patience if they are unable to quickly grasp what the writer is trying to say. Topic sentences make the writer’s basic point easy to locate and understand.

Developing the Topic Sentence

The body of a paragraph contains supporting details to help explain, prove, or expand the topic sentence. Often, in attempting to support a topic sentence with plenty of supporting details, writers discover that they need two paragraphs to support one point. For example, consider the following topic sentence, which might appear in an essay about reforming social security.

For many older Americans, retiring at 65 is not option.

Supporting sentences could include a few of the following details:

- Fact: Many families now rely on older relatives for financial support.

- Reason: The life expectancy for an average American is continuing to increase.

- Statistic: More than 20 percent of adults over age 65 are currently working or looking for work in the United States.

- Quotation: Senator Ted Kennedy once said, “Stabilizing Social Security will help seniors enjoy a well-deserved retirement.”

- Example: Last year, my grandpa took a job with Walmart because he was forced to retire early.

The personal example might be something the writer wants to expand upon in a separate paragraph, one that tells a short story about the grandfather’s decision to go back to work after retiring. The point, however, would be expressed in the topic sentence from the previous paragraph.

Sometimes, though, the topic sentence presents one idea but in presenting the supporting details, the writer gets off topic. A topic sentence guides the reader by signposting what the paragraph is about, so the rest of the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence. Can you spot the sentence in the following paragraph that does not relate to the topic sentence?

Health policy experts note that opposition to wearing a face mask during the COVID-19 pandemic is similar to opposition to the laws governing alcohol use. For example, some people believe drinking is an individual’s choice, not something the government should regulate. However, when an individual’s behavior impacts others–as when a drunk driver is involved in a fatal car accident–the dynamic changes. Seat belts are a good way to reduce the potential for physical injury in car accidents. Opposition to wearing a face mask during this pandemic is not simply an individual choice; it is a responsibility to others.

If you guessed the sentence that begins “Seat belts are” doesn’t belong, you are correct. It does not support the paragraph’s topic: opposition to regulations. If a point isn’t connected to the topic sentence, the writer should tie it in or take it out. Sometimes, the point needs to be included in another paragraph, one with a different topic sentence.

Concluding Sentences

A strong concluding sentences draws together the ideas raised in the paragraph and can set the readers up for a good transition into the next paragraph. A concluding sentence reminds readers of the main point without repeating the same words.

Concluding sentences can do any of the following:

- summarize the paragraph

- draw a conclusion based on the information in the paragraph

- make a prediction, suggestion, or recommendation about the information

For example, in the paragraph above about wearing face masks, the concluding sentence summarizes the key point: responsibility to others. The next paragraph in the essay might begin by stating something like, “Not all face masks, however, will protect people to the same degree.” The topic sentence connects the new point (which face masks are best at protecting others) with the point made in the previous paragraph (wearing face masks is a way to protect others).

Transitions

In a series of paragraphs, such as in the body of an essay, concluding sentences are often replaced by transitions. Transitions are words or phrases that help the reader move from one idea to the next, whether within a paragraph or between paragraphs. For example:

I am going to fix breakfast. Later, I will do the laundry.

“Later” transitions us from the first task to the second one. “Later” shows a sequence of events and establishes a connection between the tasks.

A transition can appear at the end of the paragraph or at the beginning of the next paragraph, but never in both places.

Look at this paragraph:

There are numerous advantages to owning a hybrid car. For example , they get up to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel-efficient, gas-powered vehicle. Also, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving. Because they do not require gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump. Given the low costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many people will buy hybrids in the future.

Each of the bold words is a transition. Transitions organize the writer’s ideas and keep the reader on track. They make the writing flow more smoothly and connect ideas.

Beginning writers tend to rely on ordinary transitions, such as “first” or “in conclusion.” There are more interesting ways to tell a reader what you want them to know. Here are some examples:

These words have slightly different meanings so don’t just substitute one that sounds better to you. Use your dictionary to be sure you are saying what you mean to say.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be? The answer is “long enough to explain your point.” A paragraph can be fairly short (two or three sentences) or, in a complex essay, a paragraph can be a page long. Most paragraphs contain three to six supporting sentences, but a s long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In some cases, even when the writer stays focused on the topic and doesn’t ramble, a long paragraph will not hold the reader’s interest. In such cases, divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a transitional word or phrase.

In an essay, a research paper, or a book, paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks. Effective writers begin a new paragraph for each new idea they introduce. If paragraphs are still a mystery to you, or if you struggle to determine when to begin a new paragraph or how to organize sentences within a paragraph, you’re not alone. Saying what a paragraph is may not be that difficult, but writing a good paragraph is. When writing a first draft of an essay, it’s highly unlikely that you will write perfect topic sentences, strong support, and excellent concluding sentences for each paragraph or that you will organize all of the information in your essay so that it’s unified around specific topic sentences. That’s why good writers revise. They know that they will need to delete, add, and re-word each of their paragraphs so that they present their ideas in a clear and forceful manner.

Key Takeaways

- Most college writing requires you to go beyond the basic five-paragraph essay structure.

- A thesis statement needs to be sophisticated and focused.

- Topic sentences express the main idea of the paragraph and usually appear at the beginning of a paragraph

- Support for the topic sentences include details, examples, quotes, statistics, and facts.

- Concluding sentences wrap-up the points made in the paragraph.

- Transitional words and phrases show how ideas relate to one another and move the reader on to the next point.

- The thesis and paragraphs in a first draft of an essay will always need to be revised

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., The Poet at the Breakfast Table (New York: Houghton & Mifflin, 1892). ↵

- The metaphor is extraordinarily useful even though the passage is annoying. Beyond the sexist language of the time, it displays condescension toward “fact-collectors” which reflects a general modernist tendency to elevate the abstract and denigrate the concrete. In reality, data-collection is a creative and demanding craft, arguably more important than theorizing ↵

- Drawn from Jennifer Haytock, Edith Wharton and the Conversations of Literary Modernism (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2008). ↵

Reading, Thinking, and Writing for College Classes Copyright © 2023 by Mary V. Cantrell is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write a Five-Paragraph Essay, With Outlines and an Example

A five-paragraph essay is a simple format for writing a complete essay, fitting the minimal components of an essay into just five paragraphs. Although it doesn’t have much breadth for complexity, the five-paragraph essay format is useful for helping students and academics structure basic papers.

If you’re having trouble writing , you can use the five-paragraph essay format as a guide or template. Below we discuss the fundamentals of the five-paragraph essay, explaining how to write one and what to include.

Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently Write with Grammarly

What is a five-paragraph essay?

The five-paragraph essay format is a guide that helps writers structure an essay. It consists of one introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs for support, and one concluding paragraph. Because of this structure, it has been nicknamed the “hamburger essay,” the “one-three-one essay,” and the “three-tier essay.”

You won’t find too many five-paragraph essay examples in literature, simply because the format is too short. The five-paragraph essay format is more popular for educational assignments, such as school papers or quick writing exercises. Think of it as a writing tool to guide structure rather than an independent genre of essay.

Part of the appeal of the five-paragraph essay format is that it can accommodate all types of essays . No matter your assignment, whether an argumentative essay or a compare-and-contrast essay , you can apply the structure of a five-paragraph essay to communicate clearly and logically, as long as your topic is simple enough to be covered in just five paragraphs .

How to start a five-paragraph essay

As with all essays, before you begin writing a five-paragraph essay, you first need to know your thesis, or main topic. Your thesis is the idea you will defend or expand upon, and ultimately what your entire essay is about, and the three paragraphs in the middle will support, prove, or elaborate on your thesis.

Naturally, you can’t begin writing until you know what you’re writing about. If your thesis is not provided in the assignment, choose one that has sufficient content for discussion, or at least enough to fill five paragraphs.

Writers typically explain the thesis in the thesis statement , a sentence in the first paragraph that tells the reader what the essay is about. You don’t need to write this first, but phrasing the topic as a single sentence can help you to understand it, focus it, and revise it if needed.

Once you’ve selected a topic, we recommend writing a quick essay outline so you know what information to include and in which paragraphs. Your five-paragraph essay outline is like a blueprint where you can perfect the order and structure of your essay beforehand to save time on editing later.

How to transition between paragraphs

One of the biggest challenges in essay writing is transitioning from one paragraph to another. Good writing is seamless and fluid, so if your paragraph transitions are jarring or abrupt, readers will get distracted from the flow and lose momentum or even interest.

The best way to move logically from one point to another is to create transition sentences using words or phrases like “however,” “similarly,” or “on the other hand.” Sometimes adding a single word to the beginning of a paragraph is enough to connect it to the preceding paragraph and keep the reader on track. You can find a full list of transition words and phrases here .

Five-paragraph essay format

If you’re writing your five-paragraph essay outline—or if you’re diving right into the first draft—it helps to know what information to include in each paragraph. Just like in all prose writing, the basic components of your essay are its paragraphs .

In five-paragraph essays, each paragraph has a unique role to play. Below we explain the goals for each specific paragraph and what to include in them.

Introductory paragraph

The first paragraph is crucial. Not only does it set the tone of your entire essay, it also introduces the topic to the reader so they know what to expect. Luckily, many of the same suggestions for how to start an essay still apply to five-paragraph essays.

First and foremost, your introductory paragraph should contain your thesis statement. This single sentence clearly communicates what the entire essay is about, including your opinion or argument, if it’s warranted.

The thesis statement is often the first sentence, but feel free to move it back if you want to open with something more attention-grabbing, like a hook. In writing, a hook is something that attracts the reader’s interest, such as mystery, urgency, or good old-fashioned drama.

Your introductory paragraph is also a good spot to include any background context for your topic. You should save the most significant information for the body paragraphs, but you can use the introduction to give basic information that your readers might not know.

Finally, your introductory paragraph should touch on the individual points made in the subsequent paragraphs, similar to an outline. You don’t want to give too much away in the first paragraph, just a brief mention of what you’ll discuss. Save the details for the following paragraphs, where you’ll have room to elaborate.

Body paragraphs

The three body paragraphs are the “meat” of your essay, where you describe details, share evidence, explain your reasoning, and otherwise advance your thesis. Each paragraph should be a separate and independent topic that supports your thesis.

Start each paragraph with a topic sentence , which acts a bit like a thesis statement, except it describes the topic of only that paragraph. The topic sentence summarizes the point that the entire paragraph makes, but saves the details for the following sentences. Don’t be afraid to include a transition word or phrase in the topic sentence if the subject change from the previous paragraph is too drastic.

After the topic sentence, fill in the rest of the paragraph with the details. These could be persuasive arguments, empirical data, quotes from authoritative sources, or just logical reasoning. Be sure to avoid any sentences that are off-topic or tangential; five-paragraph essays are supposed to be concise, so include only the relevant details.

Concluding paragraph

The final paragraph concludes the essay. You don’t want to add any new evidence or support in the last paragraph; instead, summarize the points from the previous paragraphs and tie them together. Here, the writer restates the thesis and reminds the reader of the points made in the three body paragraphs.

If the goal of your essay is to convince the reader to do something, like donate to a cause or change their behavior, the concluding paragraph can also include a call to action. A call to action is a statement or request that explains clearly what the writer wants the reader to do. For example, if your topic is preventing forest fires, your call to action might be: “Remember to obey safety laws when camping.”

The basic principles of how to write a conclusion for an essay apply to five-paragraph essays as well. For example, the final paragraph is a good time to explain why this topic matters or to add your own opinion. It also helps to end with a thought-provoking sentence, such as an open-ended question, to give your audience something to think about after reading.

Five-paragraph essay example

Here’s a five-paragraph essay example, so you can better understand how they work.

Capybaras make great pets, and the laws against owning them should be reconsidered. Capybaras are a dog-sized animal with coarse fur, native to eastern South America. They’re known across the internet as the friendliest animal on the planet, but there’s a lot of misinformation about them as pets. They’re considered an exotic animal, so a lot of legal restrictions prevent people from owning them as pets, but it’s time to reevaluate these laws.

For one thing, capybaras are rodents—the largest rodents in the world, actually—and plenty of rodents are already normalized as pets. Capybaras are closely related to guinea pigs and chinchillas, both of which are popular pets, and more distantly related to mice and rats, another common type of pet. In nature, most rodents (including capybaras) are social animals and live in groups, which makes them accustomed to life as a pet.

There are a lot of prevalent myths about capybaras that dissuade people from owning them, but most of these are unfounded. For example, people assume capybaras smell bad, but this is not true; their special fur actually resists odor. Another myth is that they’re messy, but in reality, capybaras don’t shed often and can even be litter-trained! One rumor based in truth is that they can be destructive and chew on their owners’ things, but so can dogs, and dogs are one of the most common pets we have.

The one reasonable criticism for keeping capybaras as pets is that they are high-maintenance. Capybaras require lots of space to run around and are prone to separation anxiety if owners are gone most of the day. Moreover, capybaras are semi-aquatic, so it’s best for them to have a pool to swim in. However difficult these special conditions are to meet, they’re all still doable; as with all pets, the owners should simply commit to these prerequisites before getting one.

All in all, the advantages of capybaras as pets outweigh the cons. As rodents, they’re social and trainable, and many of the deterrent myths about them are untrue. Even the extra maintenance they require is still manageable. If capybaras are illegal to own where you live, contact your local lawmakers and petition them to reconsider these laws. You’ll see first-hand just why the internet has fallen in love with this “friend-shaped” animal!

In this example, you’ll notice a lot of the points we discussed earlier.

The first sentence in the first paragraph is our thesis statement, which explains what this essay is about and the writer’s stance on the subject. Also in the first paragraph is the necessary background information for context, in this case a description of capybaras for readers who aren’t familiar with them.

Notice how each of the three body paragraphs focuses on its own particular topic. The first discusses how rodents in general make good pets, and the second dispels some common rumors about capybaras as pets. The third paragraph directly addresses criticism of the writer’s point of view, a common tactic used in argumentative and persuasive essays to strengthen the writer’s argument.

Last, the concluding paragraph reiterates the previous points and ties them together. Because the topic involves laws about keeping capybaras as pets, there’s a call to action about contacting lawmakers. The final sentence is written as a friendly send-off, leaving the reader at a high point.

Five-paragraph essay FAQ

What is a five-paragraph essay.

A five-paragraph essay is a basic form of essay that acts as a writing tool to teach structure. It’s common in schools for short assignments and writing practice.

How is it structured?

The five-paragraph essay structure consists of, in order: one introductory paragraph that introduces the main topic and states a thesis, three body paragraphs to support the thesis, and one concluding paragraph to wrap up the points made in the essay.

4.2 THE BIG PICTURE: Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Essay

The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay — often called the five-paragraph essay — are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clear thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and connecting your main idea to the world through the introduction and conclusion.

In college, you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph essay by itself is bland and formulaic. In other words, it is not very interesting to read, and it doesn’t feel very natural. More importantly, it doesn’t get you (or your reader) to think very deeply. Your professors are looking for a more ambitious, arguable, and compelling thesis with real-life evidence for all key points — all in a more organic (less artificial) structure.

What does that look like?

The five-paragraph essay, outlined below in Figure 3.1 is probably what you’re used to: the introduction starts general and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this format, the thesis uses that magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the conclusion restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers to organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

Figure 3.1 The traditional five-paragraph essay structure

Figure 3.2, in contrast, represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form that is expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply presenting a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Hm. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on.

The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph essay (Figure 3.1), it probably is not important which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (Figure 3.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next. If you changed the order of the body paragraphs, then the essay would not make sense.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay has a thesis that does not have an obvious conclusion, the reader comes to the end of the essay thinking, “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, the author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

Figure 3.2 The organic research essay structure

All that time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was not wasted. There’s an idiom in English: You have to know the rules before you can break the rules. But now is the time to move beyond an obvious thesis, loosely related body paragraphs, and a repetitive conclusion. Now is the time for you to move beyond the five-paragraph essay.

Watch this video to learn more about moving beyond the five-paragraph essay to an organic research essay:

Now practice with this exercise; it is not graded, and you may repeat it as many times as you wish:

Text adapted from: Guptill, Amy. Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence . 2022. Open SUNY Textbooks, 2016, milneopentextbooks.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/ . Accessed 16 Jan. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA

Video from: The Nature of Writing. “What’s Wrong with the Five Paragraph Essay and How to Write Organically (Animated Video).” Www.youtube.com, 3 Sept. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAlcAGVBEXU. Accessed 30 Dec. 2021.

Synthesis Copyright © 2022 by Timothy Krause is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Essay Writing: Structuring the 5-Paragraph Essay

- Essay Writing Basics

- Purdue OWL Page on Writing Your Thesis This link opens in a new window

- Paragraphs and Transitions

- How to Tell if a Website is Legitimate This link opens in a new window

- Formatting Your References Page

- Cite a Website

- Common Grammatical and Mechanical Errors

- Additional Resources

- Proofread Before You Submit Your Paper

- Structuring the 5-Paragraph Essay

"Five-Paragraph Essays"

Structuring the five-paragraph essay.

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Begins with a sentence that captures the reader’s attention

1) You may want to use an interesting example, a surprising statistic, or a challenging question.

B. Gives background information on the topic.

C. Includes the THESIS STATEMENT which:

1) States the main ideas of the essay and includes:

b. Viewpoint (what you plan to say about the topic)

2) Is more general than supporting data

3) May mention the main point of each of the body paragraphs

II. BODY PARAGRAPH #1

A. Begins with a topic sentence that:

1) States the main point of the paragraph

2) Relates to the THESIS STATEMENT

B. After the topic sentence, you must fill the paragraph with organized details, facts, and examples.

C. Paragraph may end with a transition.

III. BODY PARAGRAPH #2

B. After the topic sentence, you must fill the paragraph with organized details, facts, and examples.

IV. BODY PARAGRAPH #3

3) States the main point of the paragraph

4) Relates to the THESIS STATEMENT

V. CONCLUSION

A. Echoes the THESIS STATEMENT but does not repeat it.

B. Poses a question for the future, suggests some action to be taken, or warns of a consequence.

C. Includes a detail or example from the INTRODUCTION to “tie up” the essay.

D. Ends with a strong image – or a humorous or surprising statement.

Proofread with SWAPS

Proofreading with SWAPS

S entence Structure:

- Be sure that every sentence in paragraph supports the topic sentence.

- Avoid run-on sentences.

- Avoid sentence fragments.

W ord Usage:

- Be sure you have used the correct words (homophones) eg: there/they’re/their or to/too/two

- Avoid slang words

- Avoid pronoun overuse

A greement:

- Be sure that subjects and verbs agree in number (singular/plural)

- Keep verb tense consistent (present, past, future)

P unctuation:

- Be sure that all sentences have ending punctuation.

- Use commas after items in lists except for the last item.

- Use a comma before a coordinating conjunction.

S pelling & Capitalization:

- Check for spelling errors (manually or with a computer program)

- Begin each sentence with a capital letter.

- Check homophones.

- Capitalize proper nouns.

- Be sure apostrophes are used in contractions and possessives

Worksheet: Choosing and Narrowing Your Topic

- Worksheet - Choosing and Narrowing Your Research Topic

What is a Thesis Statement?

The final sentence in your Introduction paragraph should be your Thesis Statement.

Begin your paragraph wi th a single, clear and concise sentence stating the Topic of your essay; then, g ive your reader a roadmap for the main points you will use to support your thesis . Include the limits of your argument. End by summing up your essay’s main idea or argument with your Thesis Statement .

More help with Thesis Statements is available on this page from Rasmussen College Library .

SAMPLE INTRODUCTORY PARAGRAPHS with HIGHLIGHTED THESIS STATEMENT

All countries are unique. Obviously, countries are different from one another in location, size, language, government, climate, and lifestyle. Some countries, however, share some surprising similarities. In this case, Brazil and the United States come to mind. Some may think that these two nations have very little in common because they are in different hemispheres. On the contrary, the two countries share many similarities.

- << Previous: Proofread Before You Submit Your Paper

- Last Updated: Nov 20, 2024 4:08 PM

- URL: https://monroeuniversity.libguides.com/essaywriting

- Library (Book) Catalog |

- Research Guides |

- Library Databases |

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Dec 13, 2024 · In the classic five-paragraph essay (Figure 3.1), it probably is not important which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (Figure 3.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next. If you changed the order of the body paragraphs, then the essay would not make sense.

Content is what is in a text. Themes are more what a text is about (big ideas). Describe what is going on in the text (key features). What is this text about? What is the author’s message? What is the significance of the text to its audience? What is the text actually saying? 3. Tone and Mood

Figure 3.1 The traditional five-paragraph essay structure. All that time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was not wasted; the structure can help you organize your thinking into an easy-to-follow structure. In a college-level writing class, though, you’ll be expected to do much more with this basic formula.

The video below explains the basic five-paragraph essay structure and how you will be expected to develop a more sophisticated approach to writing for your college classes. The Thesis As the video explained, the body paragraphs in your essays are supposed to develop your thesis, and the thesis, as you may recall, is the “main idea” or ...

Let’s examine the flow of our writing by making a reverse outline of Essay 02 using its thesis statement and topic sentences. Here’s how: Start a new document. Copy and paste the your thesis statement from Essay 02. Copy and paste the topic sentence from each of the other paragraphs of your Essay 02. Correct any grammar errors.

Apr 14, 2023 · A five-paragraph essay is a simple format for writing a complete essay, fitting the minimal components of an essay into just five paragraphs. Although it doesn’t have much breadth for complexity, the five-paragraph essay format is useful for helping students and academics structure basic papers.

In the classic five-paragraph essay (Figure 3.1), it probably is not important which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (Figure 3.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next. If you changed the order of the body paragraphs, then the essay would not make sense.

Nov 20, 2024 · Begin your paragraph wi th a single, clear and concise sentence stating the Topic of your essay; then, g ive your reader a roadmap for the main points you will use to support your thesis. Include the limits of your argument. End by summing up your essay’s main idea or argument with your Thesis Statement.

3) The flow of a 5-paragraph essay no longer works when you are writing 5-to-10-page papers. o If you only have 3 body paragraphs in your essay, they are going to end up 1 to 2 pages long as your page count increases and your ideas will be hard to follow along with or focus on as your readers look at your paper.

Essay Structure In writing, following the correct essay structure is an important step in constructing a well-organized and successful essay. As a beginning step in the writing process, it is important to know the type of essay that will be developed and determine which structure would work best for its development.