What is Design Thinking in Education?

In a world where artificial intelligence, exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, is reshaping our world, the human touch of design thinking becomes even more crucial. You might already be familiar with design thinking and curious about how to harness it alongside AI, or perhaps you’re new to this method. Regardless of your experience level, I’m going to share why design thinking is your human advantage in an AI-world. We’ll explore its impact on students and educators, particularly when integrated into the curriculum to design learning experiences that are both innovative and empathetic.

Back in 2017, I spearheaded a two-year research study at Design39 Campus in San Diego, CA, focusing on how educators used design thinking to transcend traditional educational practices. This study was pivotal in understanding how to scale from pockets of innovation to a culture of innovation. It’s rare to see a public school integrate these practices, and I always wondered, “Why is this the exception and not the norm?” How might design thinking when combined with AI tools, complement standards-based curricula by prompting students to tackle real-world challenges. We investigated the methods educators used to learn about design thinking and how they crafted learning experiences at the nexus of knowledge, skills, and mindsets, aiming to foster creative problem-solving in an increasingly AI-integrated world. The results revealed it had nothing to do with the technology. It had to do with people.

Design thinking is both a method and a mindset.

What makes design thinking unique in comparison to other frameworks such as project based learning, is that in addition to skills there is an emphasis on developing mindsets such as empathy, creative confidence, learning from failure and optimism.

Seeing their students and themselves enhance and develop their skills and mindset of a design thinker demonstrated the value in using design thinking and fueled their motivation to continue. In addition, it strengthened their self-efficacy and helped them embrace, not fear change.

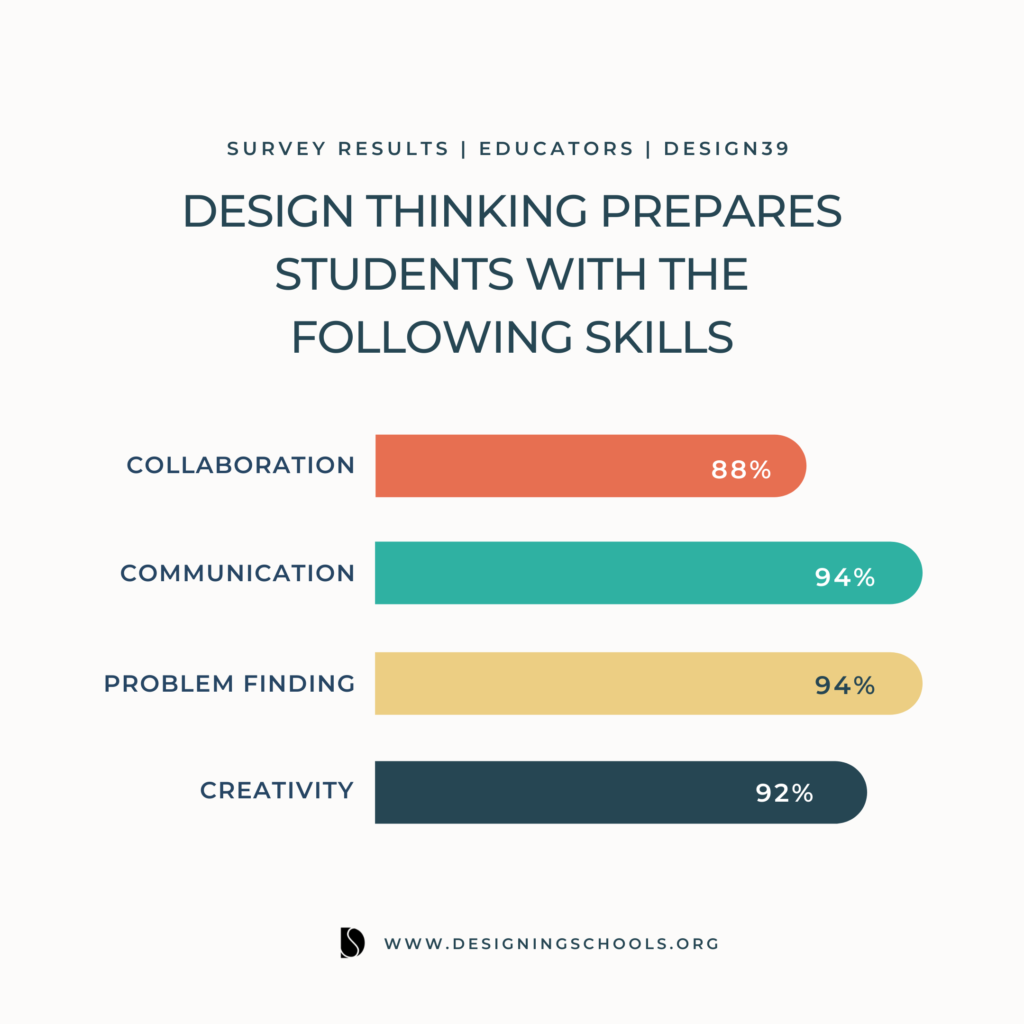

The results indicate strong agreement amongst the educators between developing in demand skills such as creativity, problem finding, collaboration and communication and practicing design thinking.

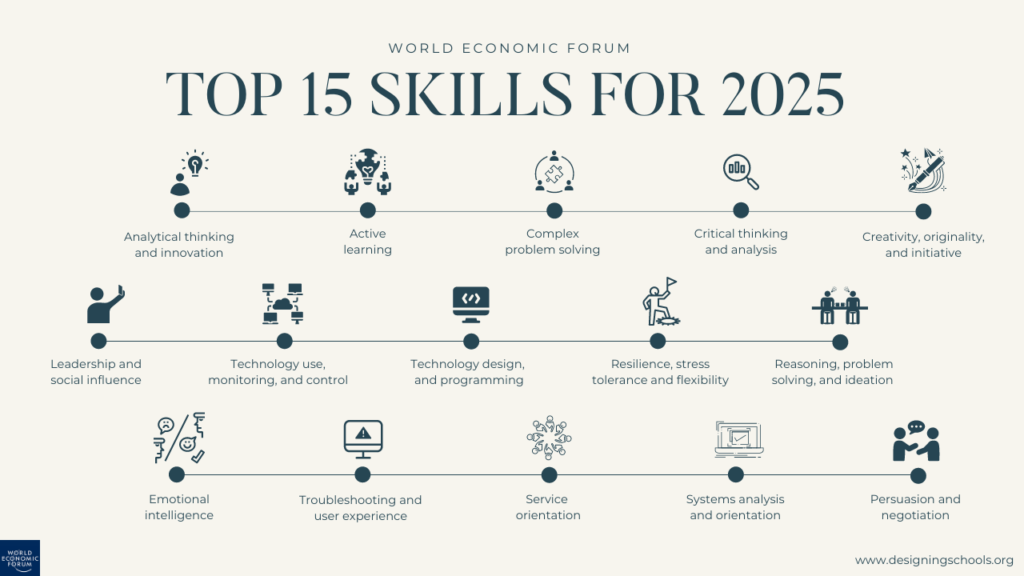

As workplaces determine how to leverage new and emerging technologies in ways that serve humanity, the two critical skills expected will be the ability to solve unstructured problems and to engage in complex communication, two areas that allow workers to augment what machines can do (Levy & Murnane, 2013.)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) call this era, “The Second Machine Age,” characterized by advances in technology, such as the rise of big data, mobility, artificial intelligence, robotics and the internet of things. The World Economic Forum calls this era, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

Regardless of the name we give this era, Schwab warned, as did Brynjolfsson and McAfee, that failure by organizations to prepare and adapt could cause inequality and fragment societies.

That era that we once talked about, is not here.

The rise of generative Ai.

As Erik Brynjolfsson shares, “There is no economic law that says as technology advances, so does equal opportunity.” The World Economic Forum reinforces this by sharing, that while the dynamics of today’s world have the potential to create enormous prosperity, the challenge to societies, particularly businesses, governments and education systems, will be to create access to opportunities that will allow everyone to share in the prosperity.

Schwab, Brynjolfsson and McAfee advocate for schools being able to play a powerful role in shaping a future that is technology-driven and human-centered. Design thinking, a human-centered framework is one method that can provide educators with the skills and mindset to navigate away from the traditional model established during the industrial area. To a learner-centered vision where we design learning experiences at the intersection of knowledge, skills, and mindsets.

The Future of Work

Designing schools for today’s learner is not just about solving a workforce or technology challenge. It’s also about solving a human challenge, where every individual has the access and opportunity to reach their potential.

Despite the changing expectations of the workplace brought forth by this era, today’s education systems largely remain unchanged. Leaving graduates without the knowledge, skills and mindsets to thrive in future workplaces and as citizens. Furthermore, the lack of equity has led to what Paul Attewell calls a growing digital use divide deepening the fragmentation of society.

A decade ago, some of the most in-demand occupations or specialties today did not exist across many industries and countries. Furthermore, 60% of children in kindergarten will live in a world where the possible opportunities do not yet exist (World Economic Forum, 2017).

In Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work, McKinsey states that 60% of all occupations have at least 30% of activities that can be automated. 40% of employers say lack of skills is the main reason for entry level job vacancies. And 60% of new graduates said they were not prepared for the world of work in a knowledge economy, noting gaps in technical and soft skills. Before our experience with ChatGPT I’m reminded of Imaginable by Jane McGonigal where she shares, “Almost everything important that’s ever happened, was unimaginable shortly before it happened.”

With an influx of technology over the past decade, with iPads and Chromebooks, and now the acceleration of AI technology, particularly over the past year, we have to wonder what gaps exist that prevent us from accelerating and scaling the change we want to see in schools.

One reason is that this challenge is complex and overwhelming. This is where design thinking practices are helpful in moving from idea to impact. Design thinking practices provide the structure and scaffolds needed to take a complex idea and simplify it.

The Design Thinking Process

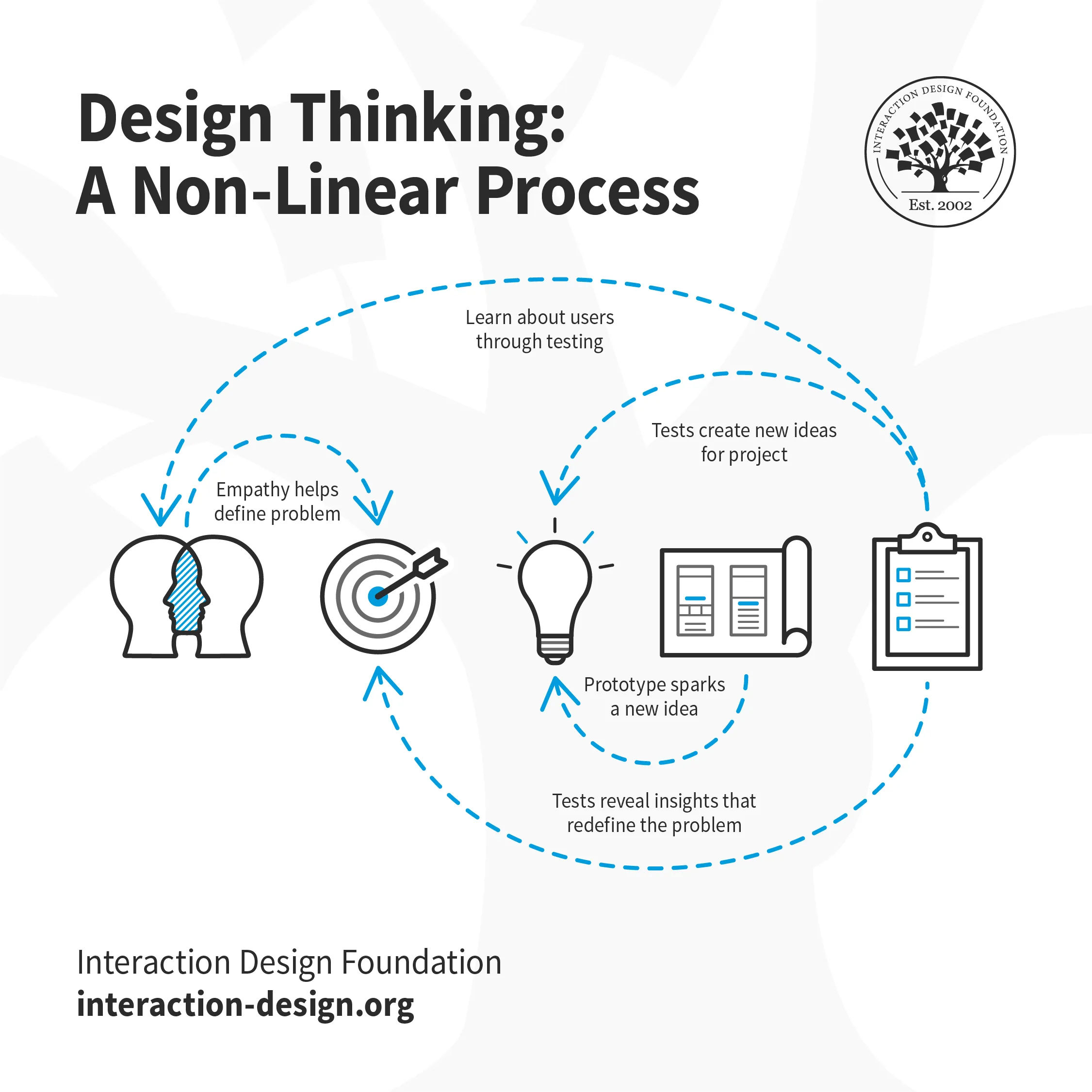

Too often design thinking is seen as a series of hexagons to jump through. Check off one and move onto the next. Design thinking is a non-linear framework that nurtures your mindset toward navigating change.

It can be used in three areas:

- Problem finding

- Problem solving

- Opportunity exploration

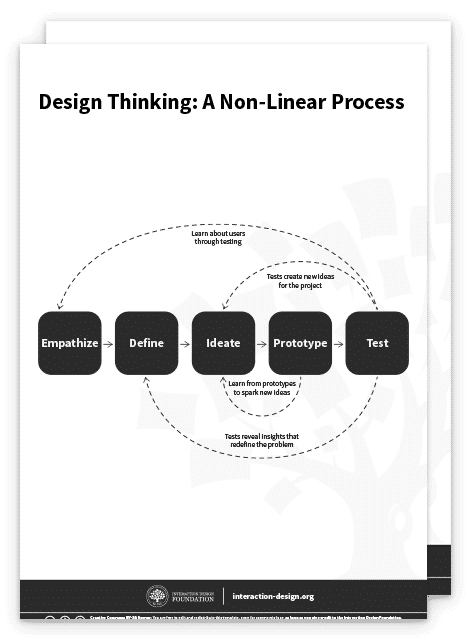

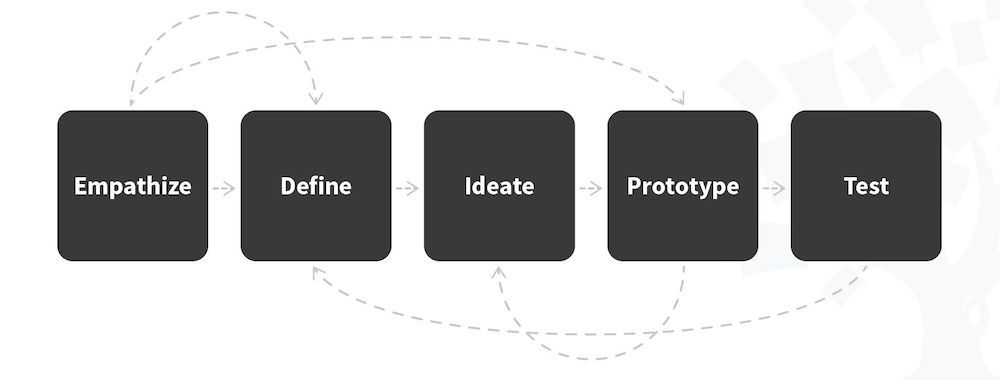

The design thinking model is nonlinear. Resulting in a back and forth between the stages of inspiration, ideation and implementation, in an effort to continuously improve upon their potential solution (Shively et al., 2018). These stages were expanded by the d.School into empathy, define, ideate, prototype and iterate. In fact, there are many exercises that can be used to apply each area of the process.

Let’s walk through each phase. Then I’ll share examples of how it is being used. I also want to preface this by saying that simply going through these stages is where most people misunderstand design thinking and don’t see the results they hoped for. These phases are here to help you develop an action-oriented mindset. Moving from identifying a problem to designing and then testing a solution to quickly get feedback. Each of these phases have numerous exercises to also help facilitate experiences based on your scenario.

Phase 1: Empathy

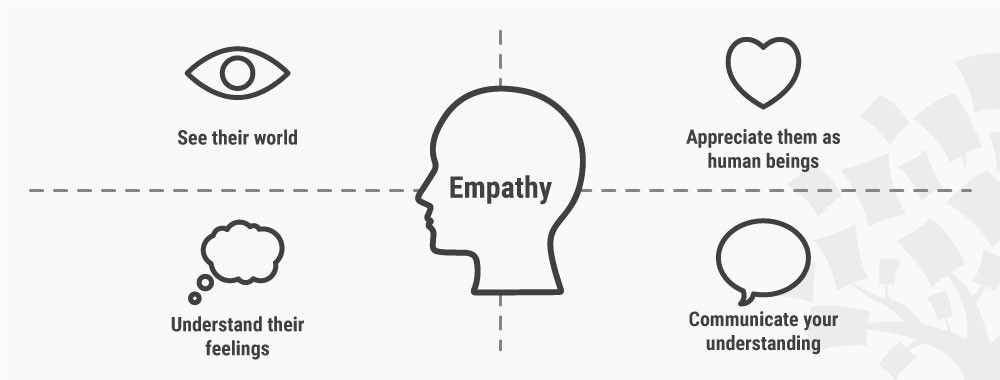

When you begin with empathy, what you think is challenged by what you learn. This alone is what makes design thinking so unique and is the first phase. During the empathy stage, you observe, engage and immerse yourself in the experience of those you are designing for. Continuously asking, “why” to understand why things are the way they are.

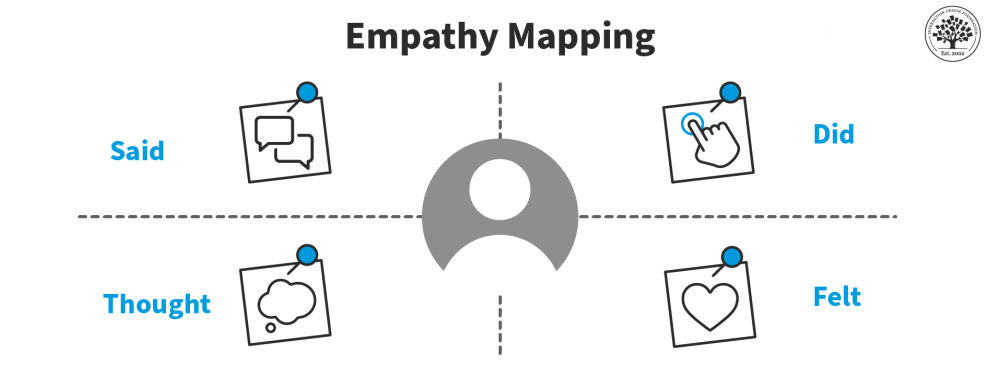

This phase is where we see the most challenges, yet this phase is the most critical. An empathy map is probably the most common exercise. Yet there are others such as, “Heard, Seen, Respected.” Another challenge in this area is not speaking directly to the user. For example, I’ve sat in many “design thinking” experiences where the group will speculate on behalf of the users. For example, educators speculating about parents, administrators speculating about teachers.

The purpose behind an empathy exercise is that when we begin with empathy, what we think is challenged by what we learn. While you can practice with each other, ultimately you must speak directly to who you are designing for.

Phase 2: Define

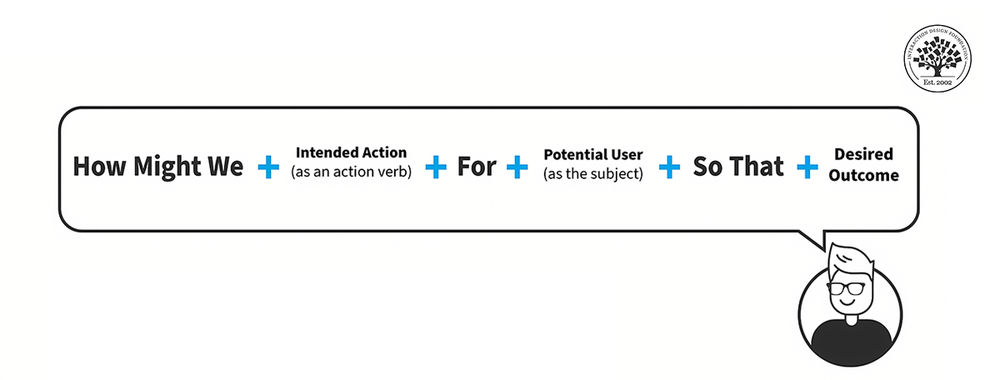

During the define stage you unpack the empathy findings and create an actionable problem statement often starting with, “how might we…” This statement not only emphasizes an optimistic outlook, it invites the designer to think about how this can be a collaborative approach.

Phase 3: Ideate

During the ideate phase you generate a series of possibilities for design. The focus here is quantity not quality. As you want to generate as many possibilities to see how they may merge together. As Guy Kawasaki shares, “Don’t worry be crappy.” Feasibility is not important at this step. Rather the key is to not think about what is possible but what can be possible. At the end, one of the ideas, or the merging of many ideas, is chosen to expand upon in the next phase.

This is another phase where we see challenges. It is not enough to simply tell someone to get a piece of paper and then come up with lots of ideas. As adults, this is incredibly challenging and is also a muscle that needs to be developed. In fact, one of my favorite exercises is 1-2-4-all. Another is walking questions, where the prompt begins with “What if…” and then after each person writes something it is handed to the person on their right.

Phase 4: Prototype

During the prototype phase, ideas that were narrowed down from ideation are created in a tangible form so that they can be tested. During this phase, the designer has an opportunity to test their prototype and gain feedback.

Phase 5: Iteration

By quickly testing the prototype, the user can refine the idea. And have a deeper understanding to go back and ask questions to the group they are designing for. The feedback received from the user allows the designer to engage in a deeper level of empathy to refine the questions asked and the problem being defined. This brings us back to phase 1.

You can find more of these exercises to lead your group through each phase at sessionlab.com .

As schools strive to create student learning experiences that prepare them for their future, design thinking can play a critical role in complementing students’ knowledge with the skills and mindsets to be creative problem solvers.

Examples of Design Thinking in K12

While new approaches tend to be viewed with skepticism, an increasing number of studies are coming forward reflecting the promise of transferability of skills and mindsets from the classroom to real-world problems when utilizing design thinking. As expectations are raised about what student skills and mindsets are needed, the level of support for educators must increase as well to experience success in new strategies and the outcomes they promise.

When student learning experiences include design thinking, their skills continue to be enhanced and developed. This in turn allows them to apply these strategies to be problem finders and problem solvers. Helping them be more comfortable with change and empowering them to solve unstructured problems. And work with new information, gaining knowledge, skills and mindsets that cannot be found in the confines of a textbook.

In “The Second Machine Age,” the authors share:

Technological progress is going to leave behind some people, perhaps even a lot of people, as it races ahead. As we’ll demonstrate, there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education. Because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only “ordinary” skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate. The Second Machine Age | Erik Brynjolfsson | Andrew McAffee

Design thinking strengthens the mindsets and skills that today’s world demands with the ability to become creative problem solvers. Through nurturing the skills and mindsets developed through engaging in design thinking, schools can create more equitable use environments for all learners that leverage technology to accelerate creative tasks that can bridge the digital use divide.

Case Study 1: Design Thinking in Grade 6

A recent study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education highlights that through instruction, students transfer design thinking strategies beyond the classroom. And that the biggest benefits were to low-achieving students (Chin et al., 2019).

The study included 200 students from grade 6. The researchers worked with the educators during class time to coach half the group of students on two specific design thinking strategies. And then assigned them a project where they could apply these skills.

The two strategies included seeking out constructive feedback and identifying multiple possible outcomes to a challenge. Each of these strategies were designed to prevent what the researchers called, “early closure”. Identifying the potential solution before examining the problem.

After class the students were presented with different challenges to see how they would approach them. The students who were taught about constructive criticism asked for feedback when presented with the new challenge and were more likely to go back and revise their work.

This area was significant, as a pre-test revealed that low-achieving students were behind their high achieving peers when seeking out feedback, a gap that the researchers say disappeared after classroom instruction, highlighting the need for this to be taught to all students, not just advanced students in electives.

As Attewell shares, “Placing computers in the hands of every student is not a solution because the challenge lies in addressing the “ digital use divide – changing the tasks that students do when provided with computers.”

He further highlights the students who gain the types of skills highlighted by the Future of Jobs Report are white and affluent students. These students are more likely to use technology to develop trending skills with greater levels of adult support. Whereas minority students are more likely to use it for rote learning tasks, with lower levels of adult support.

While design thinking is often found in pockets, presented to students already interested in this area, or the students who are in certain electives, the study led by the Stanford Graduate School of Education demonstrates the advances that can be made when this is offered to all students.

Case Study 2: Design Thinking in Geography

Another study (Caroll et al., 2010) focused on the implementation of a design curriculum during a middle school geography class. And explored how students expressed their understanding of design thinking in classroom activities, how affective elements impacted design thinking in the classroom environment and how design thinking is connected to academic standards and content in the classroom. The students were a diverse group with 60% Latino, 30% African-American, 9% Pacific Islander and 1% White.

The task was for students to use the design process to learn about systems in geography. The study found that students increased their levels of creative confidence. And that design thinking fostered the ability to imagine without boundaries and constraints. A key element to success was that educators needed to see the value of design thinking. And it must be integrated into academic content.

A challenge often associated with design thinking in education is not integrating it into mainstream education as an equitable experience for all learners despite showing that lower achieving students benefit more (Chin et al, 2019).

If students are to experience dynamic learning experiences, then organizations must raise the level of support for educators and give them the time and space to learn and integrate design thinking.

How Educators Use Design Thinking

Educators are facing a number of challenges in their professional practice. Many of the requirements today are tools and methods they did not grow up with. Furthermore, the profession is tasked with designing new methods often within traditional systems that have constraints that may serve as roadblocks to change (Robinson & Aronica, 2016).

A 2018 study by PwC with the Business Higher Education Forum shared that an average of 10% of K-12 teachers feel confident incorporating higher-level technology that affords students the opportunity to use technology to design learning that is active, not passive.

As a result, students do not spend much time in school actively practicing the higher-level trending skills expected by employers. Moreover, the report shows that more than 60% of classroom technology use is passive, while only 32% is active use. While the study suggests that many teachers do not have the skills to engage students in the active use of technology, 79% said they would like to have more professional development for how to leverage technology to design learning that is active.

Case Study 3: Design39 Campus

As I shared earlier I led a two-year research study at Design39 Campus. The study examines how it helped teachers evolve their practice. At Design39 teachers are called “Learning Experience Designers” (LEDs). Borko and Putnam (1995) share that how educators think is related to their knowledge. To understand how LEDs are using design thinking to complement the standards-based curriculum, it was important to understand how they acquired and applied this knowledge.

Despite design thinking having its roots outside of education, when asked, “What does design thinking mean to you?” The LEDs identified many commonalities amongst their own work as educators and design thinking. Moreover, they appreciated the alignment of their work with the vocabulary and structure of the design thinking framework.

Over 50% of the LEDs interviewed identified design thinking as providing them with a common vocabulary and structure for what they already do. The LEDs identified educators as inherent design thinkers due to the shared human-centered focus of working with users. In this experience educators design challenges with cyclical learning tasks involving testing, feedback and iteration, and a design mindset to address the wide variety of complex problems within their individual classrooms and across education organizations.

One LED shared:

I just look at it as a process, a process in my mind that we kind of naturally go through as educators, and so with the design thinking process I feel that it is codifying what we do and so we start off always in empathy and empathy is the heart of design thinking and so we are problem solving, who are we problem solving for – people, our learners and so this entire process that we go through of brain dumping it, trying it, getting feedback and coming back to it again so that we can make sure we were really insightful about what the problem really was for the users and we continue around this process to fine tune a potential solution is the design thinking process. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

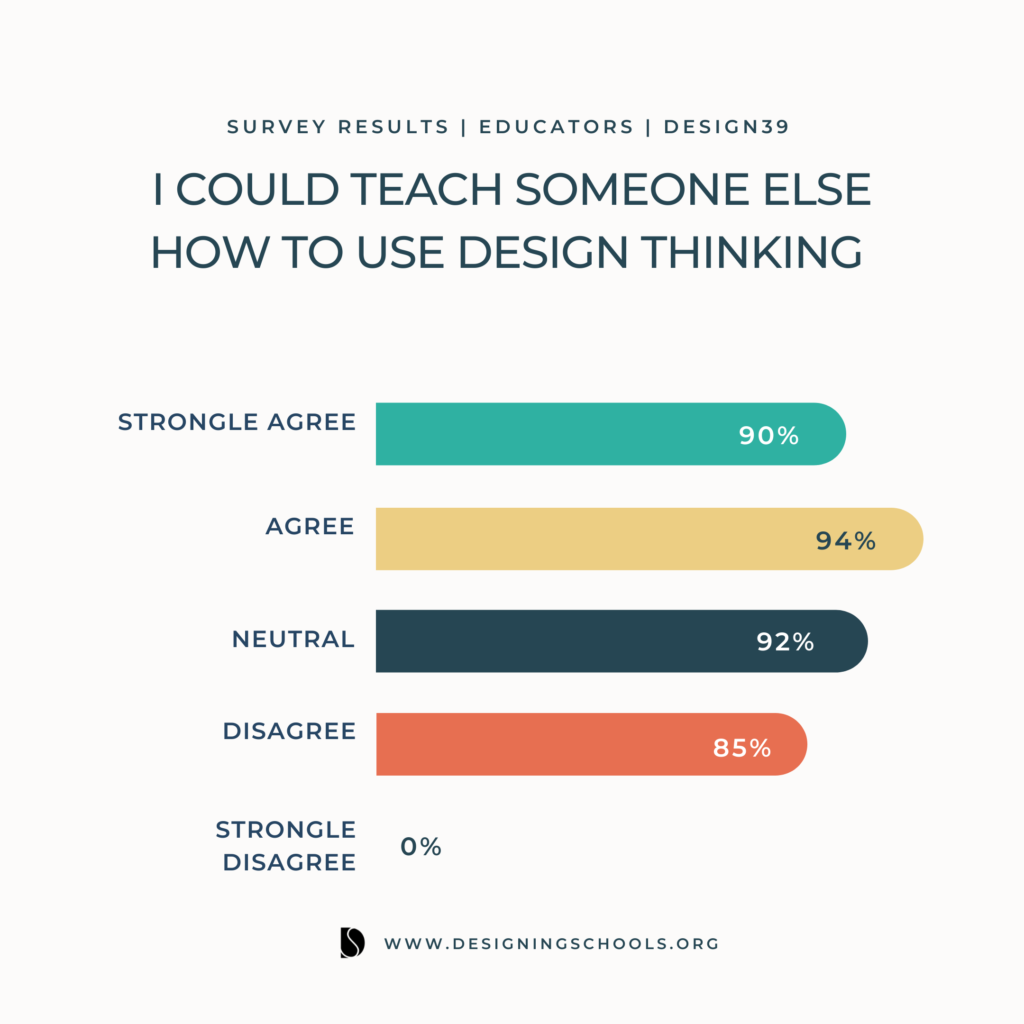

One of the ways mastery of knowledge is demonstrated is by teaching others. To assess their mastery of design thinking in education, learning experience designers were asked to describe their confidence in teaching someone else how to integrate design thinking into their curriculum.

Many LEDs acknowledged that although this is what it often looked like in the first year of the school opening, they have since had the time, space and collaborative opportunities to explore and create deeper integration. This was a point of reference mentioned by 78% of LEDs.

I think a lot of people see design thinking as one science activity, we design think everything from rules to problems that come up in the playground, it’s all through the day, they (the learners) are always looking for problems to solve. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

In another example, four LEDs made a note using the exact same language that “design thinking is not always cardboard and duct tape.” What allows them to design learning that is more meaningful one LED highlighted:

Not every day is about using duct tape and cardboard, sometimes to do the design to solve the problems you have to hunker down and read and research and so some days, design thinking is highlighting and taking notes. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

Another LED elaborated on this idea by sharing that

Design thinking is a way of thinking, not always a product that is created at the end. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

LEDs in all focus groups shared how ultimately design thinking was an opportunity to design lessons that are “ bigger than we are .”

This allowed for the LEDs to design learning experiences. With this, the end result was not to just design a potential solution to a challenge that was identified. Or to simply go from one standard to another, checking off boxes along the way, but that the solution, the work the learners were doing lived beyond the classroom for an authentic audience, where learners are working on real world problems and presenting their solutions to a real world audience.

Almost all of the LEDs shared that to them design thinking was a mindset. It is a process of inquiry that allowed for a more human centered environment where the learner was the focus.

This highlighted a critical shift in the culture at Design39, an element Sarason (2004) discussed in saying no one ever asks:

“Why is school not a place where educators learn as well?”

Bring a Design Thinking Workshop to Your School

We’ve invested in technology. Now it’s time to invest in people. Let’s discuss how design thinking practices can enhance the work you are doing in your school, giving everyone the mindset and skills to navigate change with enthusiasm and optimism. Use this calendar to schedule a time with Sabba to discuss bringing a workshop to your school. Workshops can be delivered both virtually and in-person.

Attewell, P. (2001). The first and second digital divides. Sociology of Education, 74(3), 252-259

Borko, H., & Putnam, R.T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. Gusky & M. Huberman (Eds), Professional development in education: New paradigms and practices (pp.35-65). Teachers College Press.

Brown, T & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Science Review, 8 (1), 30-35.

Brynjolfsson, E. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies (1st t ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Carroll, M., Goldman, S., Britos, L., Koh, J., Royalty, A., & Hornstein, M. (2010). Destination, imagination and the fires within: Design thinking in a middle school classroom. International Journal of Art and Design Education, (29)1, 37-53.

Chin, D. B., Doris, Blair, K.P., Wolf, R., & Conlin, L., Cutumisu, M., Pfaffman, J., Schwartz, D.L. (2019). Educating and measuring choice: A test of the transfer of design thinking in problem solving and learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 1-44.

Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2013). Dancing with Robots. NEXT Report.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017). Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work. McKinsey.

PwC (2017). Technology in U.S. Schools: Are we preparing our students for the jobs of tomorrow . Pricewater House Coopers. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/about-us/corporate-responsibility/library/preparing-students-for-technology-jobs.html .

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2016). Creative schools: the grassroots revolution that’s transforming education. Penguin Books.

Shively, K., Stith, K.M., & Rubenstein, L.D. (2018). Measuring what matters: Assessing creativity, critical thinking, and the design process. Gifted Child Today, 41(3) 149-158.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The future of jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution . World Economic Forum.

I believe that the future should be designed. Not left to chance. Over the past decade, using design thinking practices I've helped schools and businesses create a culture of innovation where everyone is empowered to move from idea to impact, to address complex challenges and discover opportunities.

stay connected

designing schools

[…] importance of learning experiences at the intersection of developing learning skills and mindsets. Design thinking is one approach that can help you master both. In my experience it’s rare that design thinking […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

« How Education Leaders Use Social Media to Build Trust, Encourage Creativity, and Inspire a Collective Vision

Creative Career Map: How Students Can Navigate the Future of Work with Design Thinking »

Browse By Category

Social Influence

Design Thinking

Join the Community

All of my best and life changing relationships began online. Whether it's a simple tweet, a DM or an email. It always begins and ends with the relationships we create. Each week I'll send the skills and strategies you need to build your human advantage in an AI world straight to your inbox.

As Simon Sinek Says: "Alone is hard. Together is better."

documentary

©DesigningSchools. All rights reserved. 2023

Instagram is my creative outlet. It's where you can see stories that take you behind the scenes and where I love having audio chats in my DM.

@designing_schools

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

The 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process

Design thinking is a methodology which provides a solution-based approach to solving problems. It’s extremely useful when used to tackle complex problems that are ill-defined or unknown—because it serves to understand the human needs involved, reframe the problem in human-centric ways, create numerous ideas in brainstorming sessions and adopt a hands-on approach to prototyping and testing. When you know how to apply the five stages of design thinking you will be impowered because you can apply the methodology to solve complex problems that occur in our companies, our countries, and across the world.

Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative process that can have anywhere from three to seven phases, depending on whom you talk to. We focus on the five-stage design thinking model proposed by the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford (the d.school) because they are world-renowned for the way they teach and apply design thinking.

What are the 5 Stages of the Design Thinking Process

The five stages of design thinking, according to the d.school, are:

Empathize : research your users' needs .

Define : state your users' needs and problems.

Ideate : challenge assumptions and create ideas.

Prototype : start to create solutions.

Test : try your solutions out.

Let’s dive into each stage of the design thinking process.

- Transcript loading…

Hasso-Platner Institute Panorama

Ludwig Wilhelm Wall, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Stage 1: Empathize—Research Your Users' Needs

Empathize: the first phase of design thinking, where you gain real insight into users and their needs.

© Teo Yu Siang and the Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

The first stage of the design thinking process focuses on user-centric research . You want to gain an empathic understanding of the problem you are trying to solve. Consult experts to find out more about the area of concern and conduct observations to engage and empathize with your users. You may also want to immerse yourself in your users’ physical environment to gain a deeper, personal understanding of the issues involved—as well as their experiences and motivations . Empathy is crucial to problem solving and a human-centered design process as it allows design thinkers to set aside their own assumptions about the world and gain real insight into users and their needs.

Depending on time constraints, you will gather a substantial amount of information to use during the next stage. The main aim of the Empathize stage is to develop the best possible understanding of your users, their needs and the problems that underlie the development of the product or service you want to create.

Stage 2: Define—State Your Users' Needs and Problems

Define: the second phase of design thinking, where you define the problem statement in a human-centered manner.

In the Define stage, you will organize the information you have gathered during the Empathize stage. You’ll analyze your observations to define the core problems you and your team have identified up to this point. Defining the problem and problem statement must be done in a human-centered manner .

For example, you should not define the problem as your own wish or need of the company: “We need to increase our food-product market share among young teenage girls by 5%.”

You should pitch the problem statement from your perception of the users’ needs: “Teenage girls need to eat nutritious food in order to thrive, be healthy and grow.”

The Define stage will help the design team collect great ideas to establish features, functions and other elements to solve the problem at hand—or, at the very least, allow real users to resolve issues themselves with minimal difficulty. In this stage, you will start to progress to the third stage, the ideation phase, where you ask questions to help you look for solutions: “How might we encourage teenage girls to perform an action that benefits them and also involves your company’s food-related product or service?” for instance.

Stage 3: Ideate—Challenge Assumptions and Create Ideas

Ideate: the third phase of design thinking, where you identify innovative solutions to the problem statement you’ve created.

During the third stage of the design thinking process, designers are ready to generate ideas. You’ve grown to understand your users and their needs in the Empathize stage, and you’ve analyzed your observations in the Define stage to create a user centric problem statement. With this solid background, you and your team members can start to look at the problem from different perspectives and ideate innovative solutions to your problem statement .

There are hundreds of ideation techniques you can use—such as Brainstorm, Brainwrite , Worst Possible Idea and SCAMPER . Brainstorm and Worst Possible Idea techniques are typically used at the start of the ideation stage to stimulate free thinking and expand the problem space. This allows you to generate as many ideas as possible at the start of ideation. You should pick other ideation techniques towards the end of this stage to help you investigate and test your ideas, and choose the best ones to move forward with—either because they seem to solve the problem or provide the elements required to circumvent it.

Stage 4: Prototype—Start to Create Solutions

Prototype: the fourth phase of design thinking, where you identify the best possible solution.

The design team will now produce a number of inexpensive, scaled down versions of the product (or specific features found within the product) to investigate the key solutions generated in the ideation phase. These prototypes can be shared and tested within the team itself, in other departments or on a small group of people outside the design team.

This is an experimental phase, and the aim is to identify the best possible solution for each of the problems identified during the first three stages . The solutions are implemented within the prototypes and, one by one, they are investigated and then accepted, improved or rejected based on the users’ experiences.

By the end of the Prototype stage, the design team will have a better idea of the product’s limitations and the problems it faces. They’ll also have a clearer view of how real users would behave, think and feel when they interact with the end product.

Stage 5: Test—Try Your Solutions Out

Test: the fifth and final phase of the design thinking process, where you test solutions to derive a deep understanding of the product and its users.

Designers or evaluators rigorously test the complete product using the best solutions identified in the Prototype stage. This is the final stage of the five-stage model; however, in an iterative process such as design thinking, the results generated are often used to redefine one or more further problems. This increased level of understanding may help you investigate the conditions of use and how people think, behave and feel towards the product, and even lead you to loop back to a previous stage in the design thinking process. You can then proceed with further iterations and make alterations and refinements to rule out alternative solutions. The ultimate goal is to get as deep an understanding of the product and its users as possible.

Did You Know Design Thinking is a Non-Linear Process?

We’ve outlined a direct and linear design thinking process here, in which one stage seemingly leads to the next with a logical conclusion at user testing . However, in practice, the process is carried out in a more flexible and non-linear fashion . For example, different groups within the design team may conduct more than one stage concurrently, or designers may collect information and prototype throughout each stage of the project to bring their ideas to life and visualize the problem solutions as they go. What’s more, results from the Test stage may reveal new insights about users which lead to another brainstorming session (Ideate) or the development of new prototypes (Prototype).

It is important to note the five stages of design thinking are not always sequential. They do not have to follow a specific order, and they can often occur in parallel or be repeated iteratively. The stages should be understood as different modes which contribute to the entire design project, rather than sequential steps.

The design thinking process should not be seen as a concrete and inflexible approach to design; the component stages identified should serve as a guide to the activities you carry out. The stages might be switched, conducted concurrently or repeated several times to gain the most informative insights about your users, expand the solution space and hone in on innovative solutions.

This is one of the main benefits of the five-stage model. Knowledge acquired in the latter stages of the process can inform repeats of earlier stages . Information is continually used to inform the understanding of the problem and solution spaces, and to redefine the problem itself. This creates a perpetual loop, in which the designers continue to gain new insights, develop new ways to view the product (or service) and its possible uses and develop a far more profound understanding of their real users and the problems they face.

The Take Away

Design thinking is an iterative, non-linear process which focuses on a collaboration between designers and users. It brings innovative solutions to life based on how real users think, feel and behave.

This human-centered design process consists of five core stages Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype and Test.

It’s important to note that these stages are a guide. The iterative, non-linear nature of design thinking means you and your design team can carry these stages out simultaneously, repeat them and even circle back to previous stages at any point in the design thinking process.

References & Where to Learn More

Take our Design Thinking course which is the ultimate guide when you want to learn how to you can apply design thinking methods throughout a design thinking process. Herbert Simon, The Sciences of the Artificial (3rd Edition), 1996.

d.school, An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE , 2010.

Gerd Waloszek, Introduction to Design Thinking , 2012.

Hero Image: © the Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide

Get Weekly Design Insights

Topics in this article, what you should read next, what is design thinking and why is it so popular.

- 1.6k shares

Personas – A Simple Introduction

- 1.5k shares

- 10 mths ago

Stage 2 in the Design Thinking Process: Define the Problem and Interpret the Results

- 1.4k shares

- 11 mths ago

What is Ideation – and How to Prepare for Ideation Sessions

- 1.3k shares

Affinity Diagrams: How to Cluster Your Ideas and Reveal Insights

- 2 years ago

Empathy Map – Why and How to Use It

- 2 weeks ago

Stage 1 in the Design Thinking Process: Empathise with Your Users

- 1.2k shares

- 4 years ago

What Is Empathy and Why Is It So Important in Design Thinking?

10 Insightful Design Thinking Frameworks: A Quick Overview

Define and Frame Your Design Challenge by Creating Your Point Of View and Ask “How Might We”

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this article , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this article.

New to UX Design? We're Giving You a Free eBook!

Download our free ebook “ The Basics of User Experience Design ” to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

IMAGES

VIDEO