Unit 1: Growth and Development

1.1 Definition and meaning of growth and development

1.2 Principles and factors affecting development

1.3 Nature vs. Nurture

1.4 Domains of development; Physical, social, emotional, cognitive, moral and language

1.5 Developmental milestones and identifying deviations and giftedness

1.1 Definition and meaning of growth and development

Human development is a lifelong process of physical, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional growth and change. These two terms, growth and development are used interchangeably. Both relate to the measurement of changes occurred in an individual after conception in the womb of the mother. However, in the strict sense of terminology, these two terms have different meanings:

Growth : can be defined as an increase in size, length, height and weight or changes in quantitative aspect of an organism/individual.

Development : is a series of orderly progress towards maturity. It implies overall qualitative changes resulting in the improved functioning of an individual.

According to Crow and Crow (1965) development is concerned with growth as well as those changes in behavior which results from environmental situation.”

1.2 Principles and factors affecting development

From the scientific knowledge gathered through observation of children, some principles have emerged. These principles enable the parents and the teachers to understand how children develop. What is expected of them? How to guide them and provide proper environment for their optimum development? It seems that the process of development is operated by some general principles. These rules or principles may be named as the principles of development. Some of these principles are briefly explained below:

1. Principle of Continuity: Development is a process which begins from the moment of conception in the womb of the mother and goes on continuing till the time of death. It is a never ending process. The changes however small and gradual continue to take place in all dimensions of one’s personality throughout one’s life.

2. Principle of Individual differences: Every organism is a distinct creation in itself. Therefore, the development which undergoes in terms of the rate and outcome in various dimensions is quite unique and specific. For example, all children will first sit up, crawl and stand before they walk. But individual children will vary in regard to timing or age at which they can perform these activities.

3. Principle of lack of uniformity in the developmental rate: Though development is a continuous process it does not exhibit steadiness and uniformity in terms of the rate of development in various dimensions of personality or in the developmental periods and stages of life. Instead of steadiness, development usually takes place in fits and starts showing almost no change at one time and a sudden spurt at another. For example, shooting up in height and sudden change in social interest, intellectual curiosity and emotional make-up.

4. Principle of uniformity of pattern: Although there seems to be a clear lack of uniformity and distinct individual differences with regard to the process and outcome of the various stages of development, yet it follows a definite pattern in one or the other dimension which is uniform and universal with respect to individuals of a species. For instance, the development of language follows a somewhat definite sequence quite common to all human beings.

5. Principle of proceeding from general to specific: While developing in relation to any aspect of personality, the child first picks up or exhibits general responses and learns to show specific and goal-directed responses afterwards. For example, a baby starts by waving his arms in general random movement and afterwards these general motor responses are converted into specific responses like grasping or reaching out. Similarly when a new born baby cries, his whole body is involved in doing so but as he develops, it is limited to the vocal cords, facial expression and eyes etc. In development of language, a baby calls all men daddy and all women mummy but as he grows and develops, he begins to use these names only for his own father and mother.

6. Principle of integration: By observing the principle of proceeding from general to specific or from the whole to the parts, it does not mean that only the specific responses are aimed for the ultimate consequences of one’s development. Rather, it is a sort of integration that is ultimately desired. It is the integration of the whole and its parts as well as the specific and general responses that enables a child to develop satisfactorily in relation to various aspects or dimensions of his personality.

7. Principle of interrelation: The various aspects of one’s growth and development are interrelated. What is achieved or not achieved in one or the other dimension in the course of the gradual and continuous process of development surely affects the development in other dimensions. All healthy body tends to develop a healthy mind and an emotionally stable and socially conscious personality. On the other hand, inadequate physical or mental development may results in a socially or emotionally maladjusted personality. That is why all efforts in education are always directed towards achieving harmonious growth and development in all aspects of one’s personality.

8. Principle of interaction: The process of development involves active interaction between the forces within the individual and the forces belonging to the individual. What is inherited by the organism at the time of conception is first influenced by the stimulations received in the womb of the mother and after birth, by the forces of physical and socio-psychological environment for its development. Therefore, at any stage of growth and development, the individual’s behaviour or personality make-up is nothing but the end-product of the constant interaction between his heredity endowment and environmental set-up.

9. Principle of interaction of maturation and learning: Development occurs as a result of both maturation and learning. Maturation refers to changes in an organism due to unfolding and ripening of abilities, characteristics, traits and potentialities present at birth. Learning denotes changes the changes in behaviour due to training and experience.

10. Principle of predictability: Development is predictable, which means that, to a great extent, we can forecast the general nature and behaviour of a child in one or more aspects or dimensions at any particular stage of its growth and development. Not only such prediction is possible along general lines but it is also possible to predict the range within which the future development of an individual child is going to fall. For example, with the knowledge of the development of the bones of a child it is possible to predict his adult structure and size.

11. Principle of cephalocaudal and proximodistal tendencies: Cephalocaudal and proximodistal tendencies are found to be followed in maintaining the orderly sequence and direction of developments.

According to cephalocaudal tendency, development proceeds in the direction of the longitudinal axis, ie. head to foot. For example, before it becomes able to stand, the child first gains control over his head and arms and then on his legs. In terms of proximodistal tendency, development proceeds from the near to the distant and the parts of the body near the centre develops before the extremities. For example, in the beginning the child is seen to exercise control over the large fundamental muscles of the arm and the hand and only afterwards the smaller muscles of the fingers.

12. Principle of spiral versus linear advancement. The path followed in development by the child is not straight and linear and development at any stage never takes place with a constant or steady pace. At a particular stage of his development, after the child had developed to a certain level, there is likely to be a period of rest for consolidation of the developmental progress achieved till then. In advancing further, development turns back and then moves forward again in a spiral pattern.

1.3 Nature vs. Nurture

The nature versus nurture debate is one of the oldest philosophical issues within psychology.

- Nature refers to all of the genes and hereditary factors that influence who we are—from our physical appearance to our personality characteristics.

- Nurture refers to all the environmental variables that impact who we are, including our early childhood experiences, how we were raised, our social relationships, and our surrounding culture.

The nature-nurture debate is concerned with the relative contribution that both influences make to human behavior.

It has long been known that certain physical characteristics are biologically determined by genetic inheritance. Color of eyes, straight or curly hair, pigmentation of the skin and certain diseases (such as Huntingdon’s chorea) are all a function of the genes we inherit. Other physical characteristics, if not determined, appear to be at least strongly influenced by the genetic make-up of our biological parents.

Height, weight, hair loss (in men), life expectancy and vulnerability to specific illnesses (e.g. breast cancer in women) are positively correlated between genetically related individuals. These facts have led many to speculate as to whether psychological characteristics such as behavioral tendencies, personality attributes and mental abilities are also “wired in” before we are even born.

Those who adopt an extreme hereditary position are known as nativists. Their basic assumption is that the characteristics of the human species as a whole are a product of evolution and that individual differences are due to each person’s unique genetic code. In general, the earlier a particular ability appears, the more likely it is to be under the influence of genetic factors.

Characteristics and differences that are not observable at birth, but which emerge later in life, are regarded as the product of maturation. That is to say we all have an inner “biological clock” which switches on (or off) types of behavior in a pre programmed way.

The classic example of the way this affects our physical development are the bodily changes that occur in early adolescence at puberty. However nativists also argue that maturation governs the emergence of attachment in infancy, language acquisition and even cognitive development as a whole.

At the other end of the spectrum are the environmentalists – also known as empiricists. Their basic assumption is that at birth the human mind is a tabula rasa (a blank slate) and that this is gradually “filled” as a result of experience (e.g. behaviorism).

From this point of view psychological characteristics and behavioral differences that emerge through infancy and childhood are the result of learning. It is how you are brought up (nurture) that governs the psychologically significant aspects of child development and the concept of maturation applies only to the biological.

For example, when an infant forms an attachment it is responding to the love and attention it has received, language comes from imitating the speech of others and cognitive development depends on the degree of stimulation in the environment and, more broadly, on the civilization within which the child is reared.

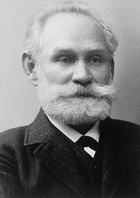

Examples of an extreme nature positions in psychology include Bowlby's (1969) theory of attachment, which views the bond between mother and child as being an innate process that ensures survival. Likewise, Chomsky (1965) proposed language is gained through the use of an innate language acquisition device. Another example of nature is Freud's theory of aggression as being an innate drive (called thanatos).

In contrast Bandura's (1977) social learning theory states that aggression is a learnt from the environment through observation and imitation. This is seen in his famous Bobo doll experiment (Bandura, 1961). Also, Skinner (1957) believed that language is learnt from other people via behavior shaping techniques.

The Nature And Nurture Theories Of Aggression

To what extent is human aggression a factor of the Nature or Nurture theories of behaviour? Human behaviour is continuously debated between scientists assessing the factors that greatly influence and shape human behaviour. This essay will focus on the biological and behavioural approaches that explain the aggressive behaviour. The two theories in this debate are the Nativist (Nature/Innate) and the Empiricist (Nurture/Learned) theories. While nativists (Nature Theory) believe that our behaviour and interactions depend upon inner established mechanisms, empiricists (Nurture Theory) link our behaviour to our experiences.

Aggression: Definition and Types

We need first to define aggression. Bushman and Anderson defined aggression in the Annual Review of Psychology 2002 as "any behaviour directed towards another individual that is carried out with the proximate intent to cause harm." Anderson et al argue that people are more likely to react aggressively to aggressively stimulating situations. The level, severity and intensity of the aggressive response vary with his personal factors that determine the individual's readiness to aggress. "Person factors include all the characteristics a person brings to the situation, such as personality traits, attitudes, and genetic predispositions.' (Anderson et al, 2010).

There are two forms of aggression, hostile and instrumental. Hostile is where the aggressive behaviour is driven by anger and is a thoughtless and unplanned action and is as an end in itself, whilst instrumental is a premeditated and proactive action, resulting in a desired goal.

Biological Approach of the Nature Theory

Introduction.

The Nature theory states that behaviours, such as aggression, are due to innate dispositions such as physiological, hormonal, neurochemicals and genetic make-up. The people who support this argument are known as nativists. The nativists accept that all characteristics of the human species as a whole are products of evolution, and that individual differences are due to a person's genetic code. Nativist theorists such as, Bowlby (1958) and Dollard et al (1939) have conducted studies that provided evidence that human behaviour is innate.

Genetic basis of Aggression

Clearly, much behaviour is innate, such as a mother's attachment to her children, the bond of partnership and love. John Bowlby (1958), a psychoanalyst, developed the evolutionary theory of attachment which suggests that children from birth are "biologically pre-programmed to form attachment with others as it is a basic survival instinct" (Saul McLeod, 2007). Bowlby believed that attachment behaviours will be automatically activated by any conditions that seem a threat, such as fear, anxiety and separation. According to this theory, babies who stay close to their mothers are more likely to survive to adulthood and have children. We can presume that both attachment and aggression are inherited.

Dollard (1939) assumed that behaviour is created by an innate human need. He was an American Psychologist and social scientist, who formulated the frustration-aggression hypothesis. The hypothesis assumes that whenever a person is inhibited from reaching their goal, an aggressive drive is provoked which motivates behaviour that causes the individual to injure another or the object that is causing the frustration. This basic drive is like behavioural units of ability that are switched on or off as an appropriate challenge or task presents itself. In other words, we act on instinct. The "Fight or Flight" mechanism is an example of a behaviour that can be switched on or off as a self-defence mechanism. These responses are hormone-mediated, and are therefore controlled by specific genetic expressions.

In further support that aggressive behaviour is inherited (Nature theory) there have been several animal experiments have been conducted by scientists that provide evidence that aggression is innate. In 1995, researchers at Hopkins University discovered a gene that was responsible for excessively violent and overly aggressive sexual behaviour in male mice. The researchers observed that once they removed a gene, the mice became more aggressive (Nelson, 1995). Nelson and his team believed that the removed gene helped the mice moderate their levels of aggression and once it was removed the behaviour was difficult to control. This indicates that genes have a significant role to play in the level of aggression. Numerous other experiments have been carried out on animals and especially mice to prove this trait. They all show a direct correlation between testosterone and aggression. (Svare 1983; Monaghan and Glickman 1992). However, it is important to note that whilst research carried out on animals clearly provides a better understanding of the effect of genes in aggression, caution must obviously be taken in extrapolating the results when trying to relate it to human behaviour. After all, human and animal brains are different, and human behaviour is far too complex for one gene to fully explain all aggressive behaviour.

However, genes need the right environment to express their phenotype characteristics. For example, an individual will grow to the height that is coded in the genes, given that the individual is well nourished and healthy. Malnourishment causes stunt growth and will stop the individual reaching the 'coded' height. The children of Guatemala have the highest rate of malnutrition in the Western Hemisphere. Their diet lacks of vital nutrients during the critical period of development from two years old, and as a result, all the children are at least six or eight inches shorter that they should be. (Gowen et al, 2010)

Behavioural Approach of the Nurture Theory

The theory of nurture suggests that human behaviour is not innate but is learned. It involves aspects of human life that surround societal reasons for why aggression is demonstrated. The National Centre of Child Abuse and Neglect (NCCAN) estimated that approximately 23 per 1,000 children are victims of maltreatment, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect (Sedlack &Broadhurst, 1996), as described by Margolin and Gordis (2004). Margolin and Gordis studied the psychological development of children exposed to violence in the family and community. They concluded that children who are in a damaged and abusive environment are more likely to become aggressive and become low achievers in their schools and communities. Therefore, family factors, peer influences and cognitive factors seem to contribute to the control and development of aggression (Sarah McCawley 2001). Bandura (1961), Rayner et al and Heusmann et al (1986) are theorists that have gathered supporting evidence to suggest aggressive behaviour is learned by observing others.

The following sections will describe the behavioural approach of the Nurture theory, by looking at the Social Learning Theory and The Script Theory.

Social Learning Theory (SLT)

Albert Bandura was a psychologist who developed the Social Learning Theory (SLT). He believed that "most human behaviour is learned observationally through modelling: from observing others one forms an idea of how new behaviours are performed, and on later occasions this coded information serves as a guide for action (1977)." (Law et al, Psychology, IB Diploma)

The theory assumes that individuals do not inherit behavioural tendencies, but learn by observing models, such as their peers and parents, and imitating their behaviour. In other words, individuals learn behaviour vicariously. In order to verify his Social Learning Theory, Bandura et al (1961) conducted a laboratory experiment to investigate if social behaviours, for example, aggression, can be acquired by imitation.

To support his theory, Bandura and his team showed young children, aged 3 to 6 years, a video of an adult model behaving aggressively towards an inflatable Bobo doll. He wanted to see if the children would imitate this behaviour. The children showed directly imitative behaviour, especially when the adult was rewarded (Law et al, Psychology, IB Diploma). This empirical study supported Bandura's theory as it showed that behaviour is the result of learning. However, it is difficult to conclude whether the child has learned the behaviour because of demand characteristics, as the child may have only imitated the behaviour in order to be acknowledged as they were being observed. However, it can be argued by those supporters of the nature theory, nativists, that without inherited characteristics, the act of learning would not be possible.

Nevertheless, Bandura's study has intrigued and inspired much research, such as Heusmann et al (1986) and Anderson et al (2001). These researchers investigated if exposure to media violence caused long-term effects and a longitudinal Meta analysis of the exposure to media violence respectively.

· Even though studies have shown that genetics can influence aggression, there are limiting factors. Aggression is more second nature to people than an uncontrollable outburst and is likely to be used as a self-defence mechanism. Situational factors are also significant, in attempting to explain how much discomfort was caused that resulted in the aggressive behaviour.

· At the other end of the spectrum is Nurture. Those who adopt nurture as an idea, empiricists or environmentalists, presume that at birth, the human mind is a blank slate (tabula rasa), and this is constantly filled as a result of experience (i.e. behaviourism). In other words, the behaviour is learned and not innate.

OTHERS EXAMPLES ARE:

Intelligence.

When someone achieves greatness thanks to an innovation or other breakthrough, it is usually agreed that the individual has a high level of intelligence. Often, when exploring the background of the individual, the influences of nature versus nurture are questioned.

· Nature - Those who would argue that nature is largely to thank for the individual’s ability to achieve greatness might point to his or her parents and use their level of intelligence as a reason for why he or she is so successful. Perhaps the child developed early skills quickly and this would be used to show that the child was clearly, “born smart.”

· Nurture - Those who would argue that a child's intelligence was affected by nurture would look at the child's educational background as well as how his or her parents raised her. These individuals would state that the intelligence level which permitted the child to be so successful, is largely the result of the child's upbringing and the school system.

Personality

The development of personality traits is often part of the nature versus nurture debate. People want to know how children develop their personalities.

· Influence of the parents - Often it is easy to see similarities between a child’s personality and one or both of her parents’ personalities. In this situation, it would seem that the child's personality has developed largely from the influence of the parents.

· Effects of nature - In some situations, children develop personalities, or tendencies toward certain behaviors, such as shyness or aggression, that can’t seem to be explained because neither parent demonstrates the same trait. In this situation, it can be argued that nature is at play in the development of the child's personality.

Homosexuality

The debate about homosexuality and whether the genesis of which is the result of nature or nurture has spanned throughout history, but has taken on even greater importance in more recent years as the rights of these individuals are being hotly debated throughout the world.

· Effects of environment - Some individuals believe that homosexuality is a choice. Others believe that it is the result of something having negatively affected an individual, such as sexual assault, causing the individual to become homosexual. These debates focus on the influence of nurture and the individuals feel that environmental factors are the cause of one’s homosexuality.

· Biological factor - Other individuals believe that homosexuality is a biological factor, no more a choice than eye color or foot size. These individuals are debating from the perspective of nature being responsible for the development of the individual.

These examples show several ways that the nature vs. nurture debate plays out in real life.

It is widely accepted now that heredity and the environment do not act independently. Both nature and nurture are essential for any behaviour, and it cannot be said that a particular behaviour is genetic and another is environmental. It is impossible to separate the two influences as well as illogical as nature and nurture do not operate in a separate way but interact in a complex manner.

1.4 Domains of development; Physical, social, emotional, cognitive, moral and language

Physical development

It is important to know how children develop physically because physical development influences children’s behaviour directly by determining what they can do and indirectly their attitudes towards self and others. Physical development involves changes in body size and body proportions which is measured in terms of height and weight. The physical development involves growth of bones, fat muscle, teeth, puberty changes of primary and secondary characteristics and neurological development.

Cognitive development

Cognition refers to the mental activities involved in acquisition, processing, organization, storage and use of information. These activities include perceiving, imagining, reasoning and judging. A single and global measure of an individual’s general level of cognitive development is called intelligence. The neuron patterns in the brain are the determining factors of intellectual development. Mental growth is the process of organization of behaviour patterning which brings the individual to a stage of psychological maturity.

The observational studies on children’s intellectual development by Jean Piaget, (1896-1980) a Swiss psychologist, is considered as an important landmark in this area. Piaget’s theory covers the entire range of ages from infancy through adolescence.

Socio-emotional development

Social and Emotional refers to your child's ability to make and maintain relationships.

Every child is born with potentialities for both pleasant and unpleasant emotions. Even infants have the ability to respond emotionally. The first sign of emotional behaviour in the new born infant's 'general excitement' due to intense stimulation. However, the emotional status of the infant in the next few months is not very clear-cut and appears to be diffused. With age, emotional responses become less diffused and random. For example, at first, the child expresses displeasure by screaming/crying but later his reactions include resisting, throwing objects, stiffening of the body etc. As the child becomes older linguistic responses increase and child's motor responses decrease especially in fear and anger.

Social development refers to development of the ability to behave in accordance with social expectations, which involve social perception, thinking and reasoning about people, one self and social relationship. These are called "Social Cognition'. The process of learning the standards of behaviors, roles and values in a given culture is called 'Socialization'. Socialization is largely determined by child's cognitive development as well as social stimulation available to the child.

Moral development

The independence that comes with adolescence requires independent thinking as well as the development of morality — standards of behavior that are generally agreed on within a culture to be right or proper . Just as Piaget believed that children’s cognitive development follows specific patterns, Lawrence Kohlberg (1984) argued that children learn their moral values through active thinking and reasoning, and that moral development follows a series of stages.

It involves an individual’s growing ability to distinguish right from wrong and to act in accordance with those distinctions.

Language development

Language involves receptive and expressive forms when receptive language ability is limited expressive language development is affected. Speech is only one form of expressive language. It is the most useful and most widely used form in expressing our thoughts and feelings. If speech is to be an useful form of communication, the speaker must use words used by others.

1.5 Developmental milestones and identifying deviations and giftedness

Developmental milestones are behaviors or physical skills seen in infants and children as they grow and develop. Rolling over, crawling, walking, and talking are all considered milestones. The milestones are different for each age range.

There is a normal range in which a child may reach each milestone. For example, walking may begin as early as 8 months in some children. Others walk as late as 18 months and it is still considered normal.

One of the reasons for well-child visits to the health care provider in the early years is to follow your child's development. Most parents also watch for different milestones. Talk to your child's provider if you have concerns about your child's development.

Closely watching a "checklist" or calendar of developmental milestones may trouble parents if their child is not developing normally. At the same time, milestones can help to identify a child who needs a more detailed check-up. Research has shown that the sooner the developmental services are started, the better the outcome. Examples of developmental services include: speech therapy, physical therapy, and developmental preschool.

Below is a general list of some of the things you might see children doing at different ages. These are NOT precise guidelines. There are many different normal paces and patterns of development.

Infant -- birth to 1 year

- Able to drink from a cup

- Able to sit alone, without support

- Displays social smile

- Gets first tooth

- Plays peek-a-boo

- Pulls self to standing position

- Rolls over by self

- Says mama and dada, using terms appropriately

- Understands "NO" and will stop activity in response

- Walks while holding on to furniture or other support

Toddler -- 1 to 3 years

- Able to feed self neatly, with minimal spilling

- Able to draw a line (when shown one)

- Able to run, pivot, and walk backwards

- Able to say first and last name

- Able to walk up and down stairs

- Begins pedaling tricycle

- Can name pictures of common objects and point to body parts

- Dresses self with only a little bit of help

- Imitates speech of others, "echoes" word back

- Learns to share toys (without adult direction)

- Learns to take turns (if directed) while playing with other children

- Masters walking

- Recognizes and labels colors appropriately

- Recognizes differences between males and females

- Uses more words and understands simple commands

- Uses spoon to feed self

Preschooler -- 3 to 6 years

- Able to draw a circle and square

- Able to draw stick figures with two to three features for people

- Able to skip

- Balances better, may begin to ride a bicycle

- Begins to recognize written words, reading skills start

- Catches a bounced ball

- Enjoys doing most things independently, without help

- Enjoys rhymes and word play

- Hops on one foot

- Rides tricycle well

- Starts school

- Understands size concepts

- Understands time concepts

School-age child -- 6 to 12 years

- Begins gaining skills for team sports such as soccer, T-ball, or other team sports

- Begins to lose "baby" teeth and get permanent teeth

- Girls begin to show growth of armpit and pubic hair, breast development

- Menarche (first menstrual period) may occur in girls

- Peer recognition begins to become important

- Reading skills develop further

- Routines important for daytime activities

- Understands and is able to follow several directions in a row

Adolescent -- 12 to 18 years

- Adult height, weight, sexual maturity

- Boys show growth of armpit, chest, and pubic hair; voice changes; and testicles/penis enlarge

- Girls show growth of armpit and pubic hair; breasts develop; menstrual periods start

- Peer acceptance and recognition is of vital importance

- Understands abstract concepts

Milestones at 6 Months

- Social/Emotional - Responds to other people’s emotions and often seems happy

- Language/Communication - Begins to say consonant sounds (jabbering with “m,” “b”)

- Cognitive - Begins to pass things from one hand to the other

- Movement/Physical - Begins to sit without support

Milestones at 9 Months

- Social/Emotional - Clingy with familiar adults; has favorite toy

- Language/Communication - Copies gestures; makes a lot of different sounds like “mamama” and “babababa”

- Cognitive - Plays peek-a-boo

- Movement/Physical - Pulls to stand; crawls

Milestones at 12 Months

- Social/Emotional - Repeats sounds or actions to get attention; is shy or nervous with strangers

- Language/Communication - Says “mama and “dada;" makes sounds with changes in tone

- Cognitive - Follows simple directions

- Movement/Physical - May stand alone

Milestones at 18 Months

- Social/Emotional - Plays simple pretend; explores with parent nearby

- Language/Communication - Points to things in a book; says several single words

- Cognitive - Know how ordinary things are used; scribbles

- Movement/Physical - Walks; eats with a spoon

Milestones at 2 Years

- Social/Emotional - Plays mainly beside other children; copies others

- Language/Communication - Uses 2-4 word sentences; knows names of body parts

- Cognitive - Plays simple make-believe; can follow a 2-step instruction

- Movement/Physical - Kicks a ball; copies straight lines and circles

Milestones at 3 Years

- Social/Emotional - Copies adults and friends

- Language/Communication - Talks well enough for strangers to understand most of the time

- Cognitive - Does puzzles with 3 or 4 pieces

- Movement/Physical - Runs easily

Developmental deviation occurs when a child acquires developmental milestones in a nonsequential fashion; children with developmental deviation acquire higher-level developmental milestones within a developmental stream before acquiring lower-level developmental milestones within that stream. Thus, developmental deviation is defined by development or behavior that is atypical at any age. Once the developmental history has been completed, a neurodevelopmental examination, which includes a traditional neurologic examination and an extended developmental evaluation, is performed. In most cases, the neurodevelopmental examination should confirm findings from the developmental history, increasing the validity of the developmental conclusions drawn from this pediatric neurodevelopmental assessment process. Once the pediatric neurodevelopmental assessment has been completed, specific developmental-behavioral diagnoses can be made.

A common misconception about gifted children is that their giftedness does not become apparent until after they start school. Gifted traits can, potentially be recognized in toddlers and even babies if you know the signs.

They may include exaggerated characteristics like:

- Constant stimulation-seeking while awake

- Earlier ability to mimic sounds than other babies

- Extreme alertness or always looking around

- Hypersensitivity to sounds, smells, textures, and tastes as well as an unusually vigorous reaction to unpleasant ones (characteristic of the Dabrowski's supersensitivities)

- Lower sleep needs than other babies

While a baby does not need to have all of these traits, most gifted children will display more than one.

It's important to note that research on gifted infants is quite limited. While these signs may suggest giftedness in childhood, they are not definitive indicators that your child will be gifted if they display these traits. If you seem to have a precious baby, encourage their brain development and watch for signs of giftedness as they continue to grow.

Assessing atypical behavior

Recognizing atypical behavior includes the following steps:

· Identify skill levels that indicate that a child’s development is atypical – either advanced or delayed – in comparison to the average child of the same age.

· Assess whether patterns of behavior are reflections of a child’s personality, are culturally influenced, or if they indicate an area of concern.

· Record the age at which skills emerge, sequence of skills, and quality of skill level as well as how they contribute to a child’s ability to function. Make a note of dates and times of occurrences to identify patterns, duration and frequency of behavior, types of activities, setting, interactions with peers, or other influences.

· Share collected information and concerns with parents and ask them to contribute any observations or insights they may have about the behavior.

· Adapt the learning program or environment to support the child’s strengths and weaknesses while providing external resources or ideas that may help parents.

Early child care providers essentially act as the parents’ partners in facilitating the developmental growth and future success of each child in their care. Due to the number of time providers spend with each child and their specialized knowledge relating to appropriate milestones, child care providers are valuable resources in recognizing and identifying potential areas that may require additional support. Early intervention can make a monumental difference in a child’s developmental progress; the involvement and concern of a skilled caregiver can have a positive impact that will last a lifetime.

- High School

- You don't have any recent items yet.

- You don't have any courses yet.

- You don't have any books yet.

- You don't have any Studylists yet.

- Information

Developmental Analysis Assignment Instructions

Human growth and development (hsco 502), liberty university, recommended for you, students also viewed.

- Developmental Analysis-Newton

- DA Rice - Because

- DA Melissa - Because

- Wk 5 DQ - Because

- Addiction no name - Because

- Addiction Nakia - Because

Related documents

- Addiction Monica - Because

- Addiction in Adolscence Essay 3-Newton

- Wk 3 Family Systems-Newton

- Family Systems summer 2015

- HSCO502 8wk Syllabus - Because

- Book Review Mc Minn Assignment Instructions

Preview text

Developmental analysis: assignment instructions, for this assignment, you will discuss your own development over your lifetime and how it, relates to the developmental concepts discussed throughout this course. the purpose of this paper, is for you to demonstrate an ability to apply a working knowledge of the theories, terminology,, and concepts of human growth and development by identifying your life as it relates to key, human growth and development concepts. you will incorporate empirical studies related to, development, readings, and videos., instructions, you will use developmental theories and concepts to analyze your own developmental processes, focusing on adulthood. use a variety in your sentence structure and wording. you should not use, direct quotes, but rather summarize and paraphrase insight from your sources. you will use your, textbook and at least 3 other scholarly sources (no less than 4 sources total) to create your, developmental analysis. your paper must be at least 10 pages including a title page, abstract, 6, pages in the body, and a reference page. remember: the title page, abstract, and references are, not a part of the body of the paper; you must have at least 7 pages of content besides these., title page – use current apa format., use the following headings to organize your content:, personal development introduction, provide a concise introduction to significant personal characteristics, family dynamics and, support structures, and meaningful events or occurrences. this section should be no more than 1, theoretical perspectives of development, stage of development according to piaget, examine the portion of your textbook or outside references that detail(s) piaget’s theory of, cognitive development. explain how these stages are relevant to your own childhood and, adolescent developmental processes. you must identify specific stages, characteristics of that, stage and offer explanation and examples that parallel to your own developmental processes., nature versus nurture, examine the portion of your textbook or outside references that detail(s) elements of the nature, versus nurture influences. this section of the paper must analyze how you have been impacted, from a nature versus nurture standpoint in your childhood and adolescent developmental, processes. provide explanation and examples., postformal thought according to perry, page 1 of 3, explain how the process of moving from dualism to relativism is applicable to your own thought, development. refer to the portion of your textbook or outside references that address(es) perry’s, theory of intellectual and ethical development in the college years. focus on the period of, adulthood and how you have grown into your current stage of cognitive and moral development., adult attachment and relationships, explain the parallels between attachment theory and your childhood and adolescent experiences, with a care provider. specify a specific attachment style, characteristics of the style, and, behavioral consequences and outcomes. examine the portion of your textbook or outside, references that address(es) the attachment prototypes in peer/romantic tradition. provide, explanations and examples of your own adult attachment challenges and strengths. also, use the, insights from the portion of the textbook or outside references that address(es) research on young, adult dyadic relationships to draw conclusions about your partnership selection, elements of, intimacy, satisfaction, and stability, as well as communication styles and conflict resolution., career development process: super’s approach (chapter 12), examine the portion of your textbook or outside references that address(es) the super, developmental approach to determine what stage you are currently in and what you anticipate, will be important influences in the future for you to move into the next stage or maintain a, current stage., identity development, examine the portion of your textbook or outside references that detail(s) erikson’s psychosocial, stages of development. explain how these are relevant to your own childhood and adolescent, developmental processes. you must identify specific stages, characteristics of those stages, and, parallels to your own developmental processes. what challenges or strengths related to, psychosocial development did you exhibit that either hindered or helped your progression, through these developmental crises during childhood and adolescence use examples to, illustrate application of these to your development history. also examine the portion of your, textbook or outside references that address(es) erikson’s theory related to adulthood. depending, on your age and life experience, identify which stage of erikson’s psychosocial development you, are in and examine how you managed the crisis period are there any notable influences, good, or bad, that will help you navigate successfully to the next stage, faith development, using fowler’s stages of faith and identity (found in the module 5: week 5 learn folder),, explain how the stages are relevant to your own childhood and adolescent developmental, processes. you must identify specific stages and demonstrate how they are relevant and, applicable to your own development history. you may also extend your dialogue to integrate, christian principles and biblical themes as appropriate., personality and temperament, examine the portion of your textbook or outside references that address(es) the big 5 personality, traits. provide explanations and examples of your own personality and temperament, characteristics in adulthood related to these personality traits. remember that everyone is on a, spectrum of each of these traits – e., one might be high on extraversion and low on, conscientiousness., page 2 of 3.

- Multiple Choice

Course : Human Growth and Development (HSCO 502)

University : liberty university.

- More from: Human Growth and Development HSCO 502 Liberty University 74 Documents Go to course

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Chapter 1: Introduction to Child Development

Chapter objectives.

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the principles that underlie development.

- Differentiate periods of human development.

- Evaluate issues in development.

- Distinguish the different methods of research.

- Explain what a theory is.

- Compare and contrast different theories of child development.

Introduction

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn.

We will look at how we change physically over time from conception through adolescence. We examine cognitive change, or how our ability to think and remember changes over the first 20 years or so of life. And we will look at how our emotions, psychological state, and social relationships change throughout childhood and adolescence. 1

Principles of Development

There are several underlying principles of development to keep in mind:

- Development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan (although this text ends with adolescence). And early experiences affect later development.

- Development is multidirectional. We show gains in some areas of development, while showing loss in other areas.

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions; physical, cognitive, and social and emotional.

- The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness.

- The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language.

- The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.

All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains.

- Development is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change and that many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient (able to overcome adversity).

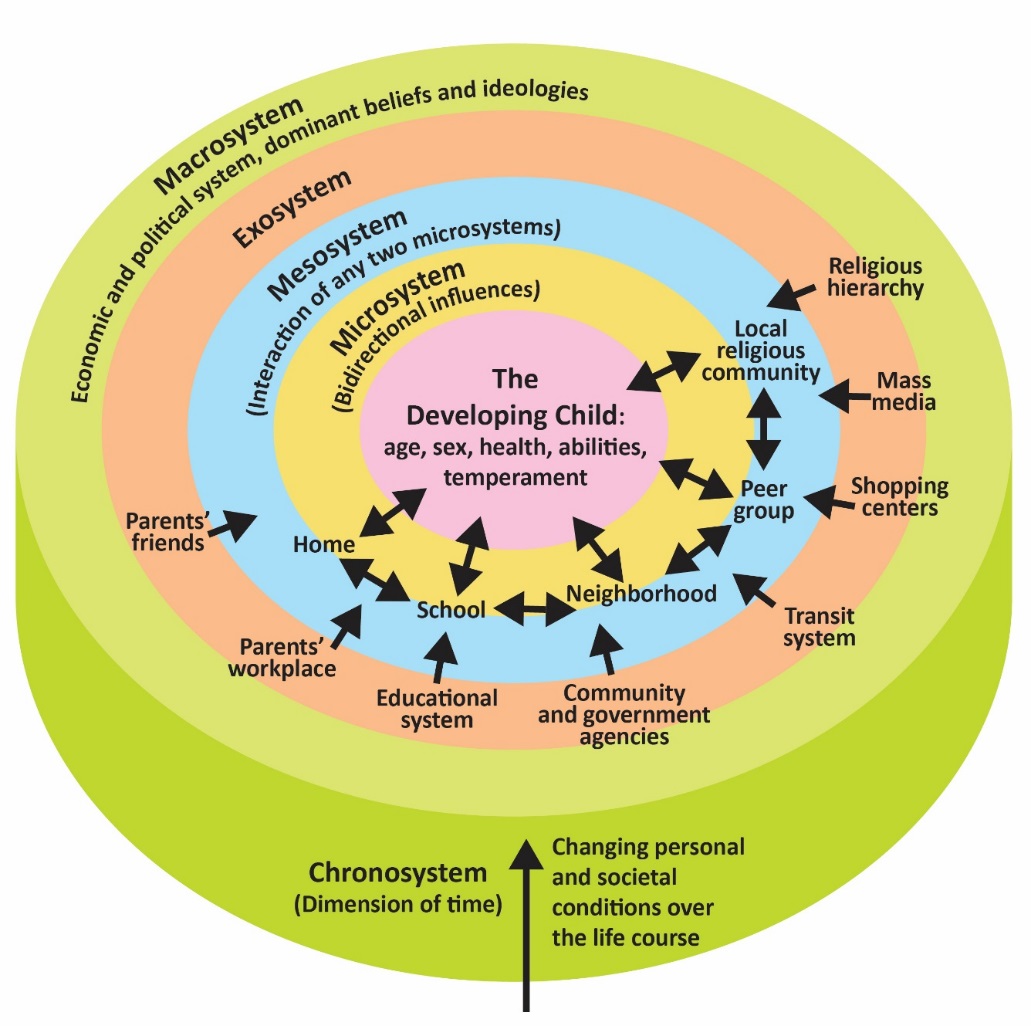

- Development is multicontextual. 2 We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. The key here is to understand that behaviors, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture. 3

Now let’s look at a framework for examining development.

Periods of Development

Think about what periods of development that you think a course on Child Development would address. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: infancy, childhood, and teenagers. Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these five stages as follows:

- Prenatal Development (conception through birth)

- Infancy and Toddlerhood (birth through two years)

- Early Childhood (3 to 5 years)

- Middle Childhood (6 to 11 years)

- Adolescence (12 years to adulthood)

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adolescence that will be explored in this book. So while both an 8 month old and an 8 year old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive.

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Figure 1.1 – A tiny embryo depicting some development of arms and legs, as well as facial features that are starting to show. 4

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Figure 1.2 – A swaddled newborn. 5

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

Figure 1.3 – Two young children playing in the Singapore Botanic Gardens 6

Middle Childhood

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. And children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Figure 1.4 – Two children running down the street in Carenage, Trinidad and Tobago 7

Adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. 8

Figure 1.5 – Two smiling teenage women. 9

There are some aspects of development that have been hotly debated. Let’s explore these.

Issues in Development

Nature and nurture.

Why are people the way they are? Are features such as height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc. the result of heredity or environmental factors-or both? For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any particular feature, those on the side of Nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of Nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

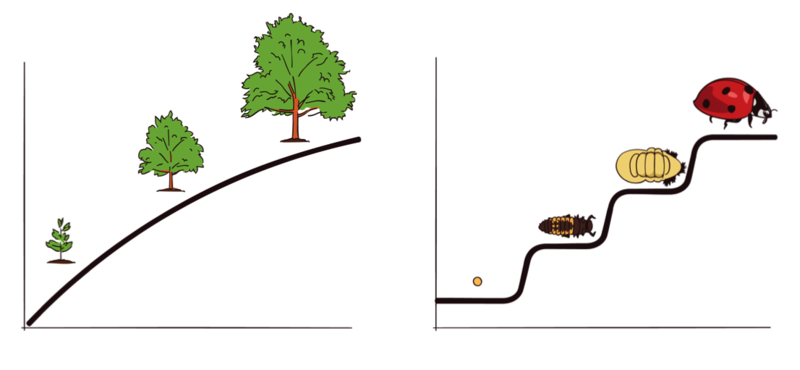

Continuity versus Discontinuity

Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories or discontinuous development assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more developed skills.

Figure 1.6 – The graph to the left shows three stages in the continuous growth of a tree. The graph to the right shows four distinct stages of development in the life cycle of a ladybug. 10

Active versus Passive

How much do you play a role in your own developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their own development. Piaget, for instance believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. In contrast, many behaviorists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process. 11

How do we know so much about how we grow, develop, and learn? Let’s look at how that data is gathered through research

Research Methods

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Some people are hesitant to trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality) or based on what others have told you or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry. Read the following sentence aloud:

Paris in the

Are you sure that is what it said? Read it again:

If you read it differently the second time (adding the second “the”) you just experienced one of the problems with personal inquiry; that is, the tendency to see what we believe. Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence. Popper suggests that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). Theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons guard against bias.

Scientific Methods

One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making your findings available to others (both to share information and to have your work scrutinized by others)

Your findings can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest and through this process a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantifying or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied. Many academic journals publish reports on studies conducted in this manner.

Another model of research referred to as qualitative research may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest

- Ask open ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers are to be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

Let’s look more closely at some techniques, or research methods, used to describe, explain, or evaluate. Each of these designs has strengths and weaknesses and is sometimes used in combination with other designs within a single study.

Observational Studies

Observational studies involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play at a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event (such as observing children in a classroom and capturing the details about the room design and what the children and teachers are doing and saying). In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. What people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. Children tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect) and may not survey well.

Experiments

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables) in a controlled setting in efforts to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. A variable is anything that changes in value. Concepts are operationalized or transformed into variables in research, which means that the researcher must specify exactly what is going to be measured in the study.

Three conditions must be met in order to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs are useful in meeting these conditions.

The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, when one is altered, the other changes in response. (The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable. For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.)

The cause must come before the effect. Experiments involve measuring subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So we would measure the subjects’ level of stress before introducing exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there has been a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events, which makes understanding causality problematic with these designs.)

The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown variables are actually causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would make sure that our subjects’ diets were held constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, diet might really be creating the change in stress level rather than exercise.

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or subset of a population) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two groups: the experimental group or the control group. The experimental group is the group that is going to be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher is introducing as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison and is going to have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are in a better position to suggest that the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable.

The major advantage of the experimental design is that of helping to establish cause and effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty of translating much of what happens in a laboratory setting into real life.

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison.

Figure 1.7 – Illustrated poster from a classroom describing a case study. 12

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” This is known as Likert Scale . Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many independent and dependent variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Of course, surveys can be designed in a number of ways. They may include forced choice questions and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So a lot of time and effort should be placed on the construction of survey items. One of the benefits of having forced choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. Analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed in a different way. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report or what people say they do rather than on observation and this can limit accuracy.

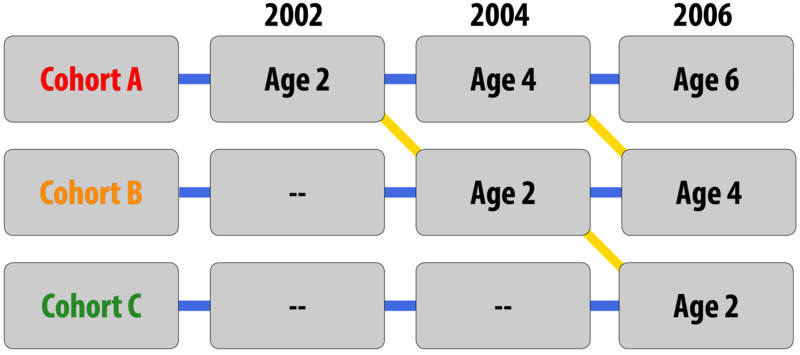

Developmental Designs

Developmental designs are techniques used in developmental research (and other areas as well). These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

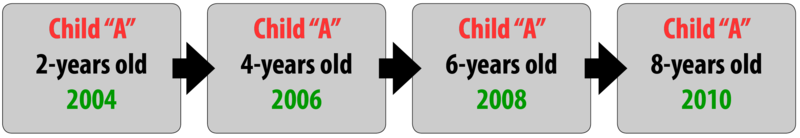

Longitudinal Research

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background, and measuring them repeatedly over a long period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with them when they were younger.

Figure 1.8 – A longitudinal research design. 13

A problem with this type of research is that it is very expensive and subjects may drop out over time. The Perry Preschool Project which began in 1962 is an example of a longitudinal study that continues to provide data on children’s development.

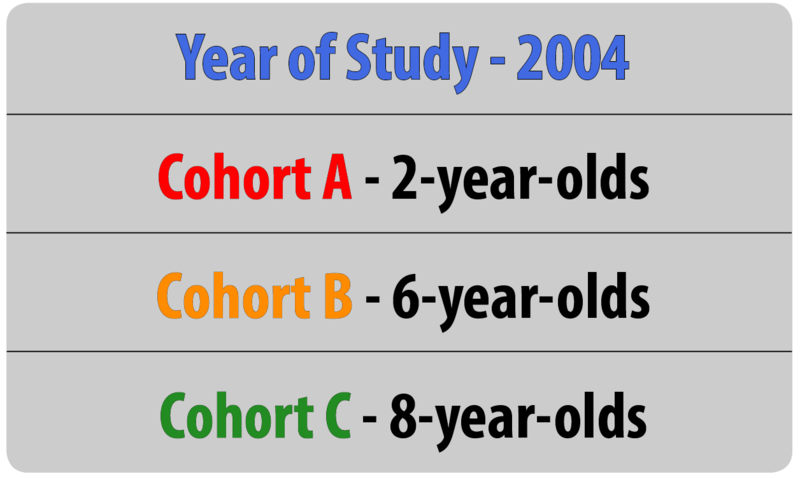

Cross-sectional Research

Cross-sectional research involves beginning with a sample that represents a cross-section of the population. Respondents who vary in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class might be asked to complete a survey about television program preferences or attitudes toward the use of the Internet. The attitudes of males and females could then be compared, as could attitudes based on age. In cross-sectional research, respondents are measured only once.

Figure 1.9 – A cross-sectional research design. 14

This method is much less expensive than longitudinal research but does not allow the researcher to distinguish between the impact of age and the cohort effect. Different attitudes about the use of technology, for example, might not be altered by a person’s biological age as much as their life experiences as members of a cohort.

Sequential Research

Sequential research involves combining aspects of the previous two techniques; beginning with a cross-sectional sample and measuring them through time.

Figure 1.10 – A sequential research design. 15

This is the perfect model for looking at age, gender, social class, and ethnicity. But the drawbacks of high costs and attrition are here as well. 16

Table 1 .1 – Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Research Designs 17

Consent and Ethics in Research

Research should, as much as possible, be based on participants’ freely volunteered informed consent. For minors, this also requires consent from their legal guardians. This implies a responsibility to explain fully and meaningfully to both the child and their guardians what the research is about and how it will be disseminated. Participants and their legal guardians should be aware of the research purpose and procedures, their right to refuse to participate; the extent to which confidentiality will be maintained; the potential uses to which the data might be put; the foreseeable risks and expected benefits; and that participants have the right to discontinue at any time.

But consent alone does not absolve the responsibility of researchers to anticipate and guard against potential harmful consequences for participants. 18 It is critical that researchers protect all rights of the participants including confidentiality.

Child development is a fascinating field of study – but care must be taken to ensure that researchers use appropriate methods to examine infant and child behavior, use the correct experimental design to answer their questions, and be aware of the special challenges that are part-and-parcel of developmental research. Hopefully, this information helped you develop an understanding of these various issues and to be ready to think more critically about research questions that interest you. There are so many interesting questions that remain to be examined by future generations of developmental scientists – maybe you will make one of the next big discoveries! 19

Another really important framework to use when trying to understand children’s development are theories of development. Let’s explore what theories are and introduce you to some major theories in child development.

Developmental Theories

What is a theory.

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories…” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. But theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior; in fact they are proposed explanations for the “how” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3 year old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that requires assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which a number of single cases are observed and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist develops ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them. 20

Let’s take a look at some key theories in Child Development.

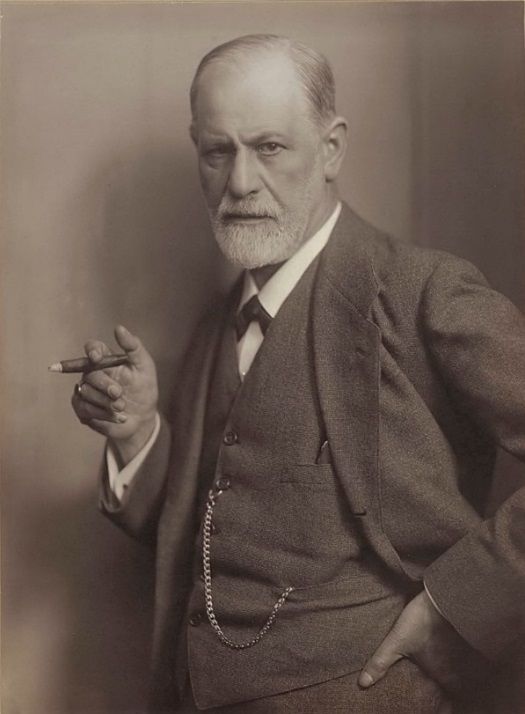

Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

We begin with the often controversial figure, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resilience in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Figure 1.11 – Sigmund Freud. 21

Freud’s theory of self suggests that there are three parts of the self.

The id is the part of the self that is inborn. It responds to biological urges without pause and is guided by the principle of pleasure: if it feels good, it is the thing to do. A newborn is all id. The newborn cries when hungry, defecates when the urge strikes.

The ego develops through interaction with others and is guided by logic or the reality principle. It has the ability to delay gratification. It knows that urges have to be managed. It mediates between the id and superego using logic and reality to calm the other parts of the self.

The superego represents society’s demands for its members. It is guided by a sense of guilt. Values, morals, and the conscience are all part of the superego.

The personality is thought to develop in response to the child’s ability to learn to manage biological urges. Parenting is important here. If the parent is either overly punitive or lax, the child may not progress to the next stage. Here is a brief introduction to Freud’s stages.

Table 1. 2 – Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is very difficult to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which to elaborate and modify subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views. 22

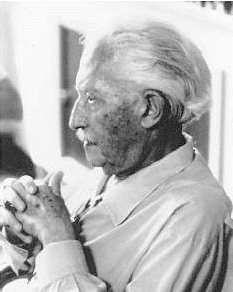

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

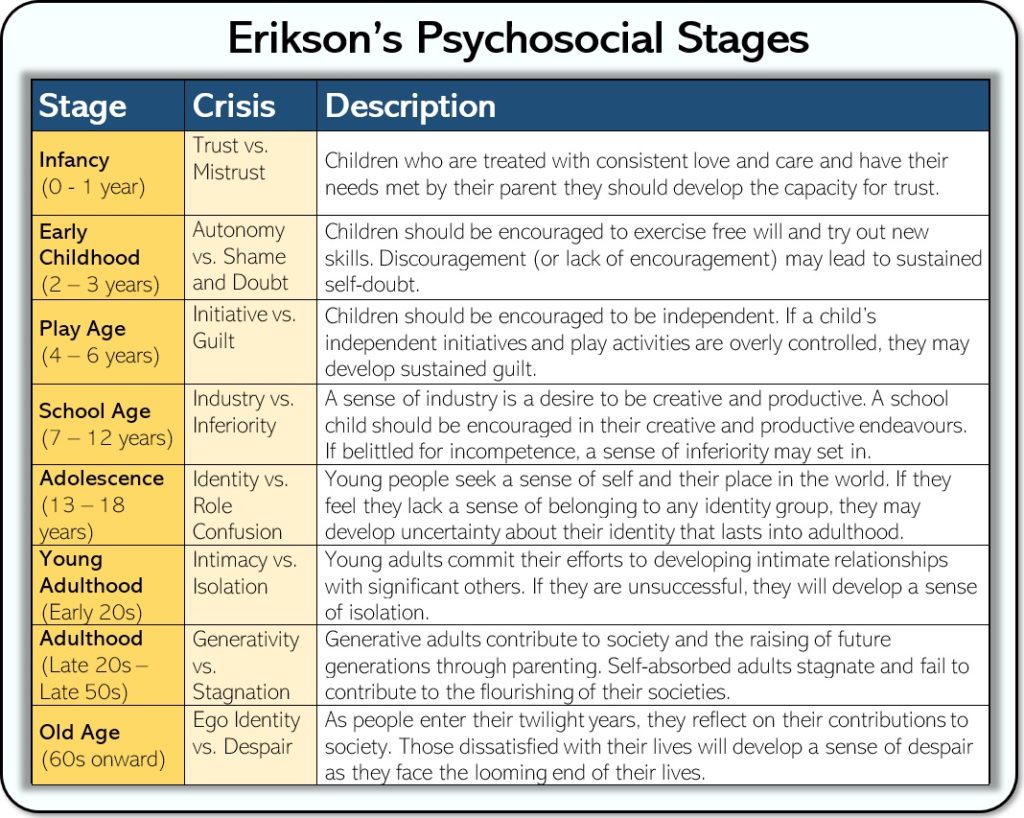

Now, let’s turn to a less controversial theorist, Erik Erikson. Erikson (1902-1994) suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development. Erikson was a student of Freud’s but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and we consciously think about how to achieve our goals. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Figure 1.12 – Erik Erikson. 23

Erikson expanded on his Freud’s by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968). He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living. Here is a brief overview of the eight stages:

Table 1. 3 – Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices. 24

Behaviorism