- 3 . 01 . 20

- Leaving Academia

Is a PhD Worth It? I Wish I’d Asked These 6 Questions First.

- Posted by: Chris

Updated Nov. 19, 2022

Is a PhD worth it?

Should I get a PhD?

A few people admit to regretting their PhD. Most—myself included — said that they don’t ( I wrote about why in this post ).

But we often say we don’t regret stupid things we’ve done or bad things that happen to us. This means we learned from them, not that we wanted them to happen.

So just because PhDs don’t regret it, doesn’t mean it was worth it.

But if you were to ask, Is a PhD worth it, it’s a different and more complicated question.

When potential PhD students ask me for advice, I hate giving it. I can’t possibly say whether it will be worth it for them. I only know from experience that for some PhDs the answer is no.

In this post, I’ll look at this question from five different directions, five different ways that a PhD could be worth it. Then I give my opinion on each one. You can tell me if I got the right ones of if I’m way off base. So here we go.

This is post contains affiliate links. Thanks for supporting Roostervane!

tl;dr It’s up to you to make it worth it. A PhD can hurt your finances, sink you in debt, and leave you with no clear path to success in some fields. But PhDs statistically earn more than their and have lower unemployment rates. A PhD also gives you a world-class mind, a global network, and a skill set that can go just about anywhere.

Should I Get a PhD?

tl;dr Don’t get a PhD by default. Think it through. Be clear about whether it’s going to help you reach career goals, and don’t expect to be a professor. A few rules of thumb- make sure you know where you want to go and whether a PhD is the ONLY way to get there, make sure it’s FUNDED (trust me), and make sure your program has strong ties into industry and a record of helping its students get there.

1. Is a PhD worth it for your finances?

My guess: Not usually

People waste a lot of their best years living on a grad stipend. To be honest, my money situation was pretty good in grad school. I won a large national grant, I got a ton of extra money in travel grants, and my Canadian province gave me grants for students with dependents. But even with a decent income, I was still in financial limbo–not really building wealth of any sort.

And many students scrape by on very small stipends while they study.

When it comes to entering the marketplace, research from Canada and the United States shows that PhD students eventually out-earn their counterparts with Master’s degrees. It takes PhDs a few years to find their stride, but most of us eventually do fine for earnings if we leave academia. Which is great, and perhaps surprising to many PhDs who think that a barista counter is the only non-academic future they have .

The challenge is not income–it’s time. If you as a PhD grad make marginally more than a Master’s graduate, but they entered the workforce a decade earlier, it takes a long time for even an extra $10,000 a year to catch up. The Master’s grad has had the time to build their net worth and network, perhaps buy a house, pay down debt, invest, and just generally get financially healthy.

While PhDs do fine in earnings in the long run, the opportunity cost of getting the PhD is significant.

The only real way to remedy this—if you’ve done a PhD and accumulating wealth is important to you, is to strategically maximize your earnings and your value in the marketplace to close the wealth gap. This takes education, self-discipline, and creativity, but it is possible.

I tried to calculate the opportunity cost of prolonging entry into the workforce in this post .

2. Is a PhD worth it for your career?

My guess: Impossible to tell

Most of my jobs have given me the perfect opportunity to see exactly where I could be if I’d stopped at a Master’s degree, often working alongside or for those who did and are further ahead. In terms of nuts and bolts of building career experience section on a resume, which is often the most important part, a PhD is rarely worth it. (Some STEM careers do require a PhD.)

However, at the start of my post-graduate educational journey, I was working part-time running teen programs and full time as a landscaper. I had an undergraduate degree. Despite my job and a half, I was still poor. My life had no direction, and had I not begun my Master’s to PhD journey I probably would have stayed there.

The PhD transformed me personally. It did this by developing my skills, or course. But even more so, it taught me that anything is possible. It took a poor kid from a mining town in northern Canada and gave me access to the world. It made my dreams of living abroad come true. I learned that anything is possible. And that will never go away.

It’s changed the course of my life and, subsequently, my career.

It’s impossible for you to know if it’s worth it for your career. But you can build a hell of a career with it.

So it wouldn’t be fair for me to say, “don’t get a PhD.” Because it worked out for me, and for some it does.

But there are a heck of a lot of people who haven’t figured out how to build a career with this thing. Which is one of the reasons Roostervane exists in the first place.

Psst! If you’re looking at doing a PhD because you don’t know where to go next with your career–I see you. Been there. Check out my free PDF guide– How to Build a Great Career with Any Degree.

3. Is a PhD worth it for your personal brand?

My guess: Probably

There’s some debate over whether to put a Dr. or PhD before or after your name. People argue over whether it helps in the non-academic marketplace. Some feel that it just doesn’t translate to whatever their new reality is. Some have been told by some manager somewhere that they’re overqualified and pulled themselves back, sometimes wiping the PhD off their resume altogether.

The truth is, if you have a PhD, the world often won’t know what to do with it. And that’s okay. Well-meaning people won’t understand how you fit into the landscape, and you may have to fight tooth and nail for your place in it. People may tell you they can’t use you, or they might go with what they know—which is someone less qualified and less-educated.

It happens.

But someone with a PhD at the end of their name represents an indomitable leader. So grow your possibilities bigger and keep fighting. And make your personal brand match those three little letters after your name. Do this so that the world around can’t help but see you as a leader. More importantly, do it so that you don’t forget you are.

Should I put “PhD” after my name on LinkedIn?

5 reasons you need to brand yourself

4. Is a PhD worth it for your sense of purpose?

Is getting a PhD worth it? For many people the answer is no.

PhDs are hurting.

If you’ve done one, you know. Remember the sense of meaning and purpose that drew you towards a PhD program? Was it still there at the end? If yours was, you’re lucky. I directed my purpose into getting hired in a tenure-track job, and got very hurt when it didn’t happen.

And people have vastly different experiences within programs.

Some people go through crap. But for them their research is everything and putting up with crap is worth it to feel like they have a sense of purpose. Many PhDs who are drawn into programs chasing a sense of purpose leave deeply wounded and disenchanted, ironically having less purpose when they started.

While new PhDs often talk about the PhD as a path do doing “something meaningful,” those of us who have been through entire programs have often seen too much. We’ve either seen or experienced tremendous loss of self. Some have friends who didn’t make it out the other end of the PhD program.

But there are some PhDs who have a great experience in their programs and feel tremendously fulfilled.

As I reflect on it, I don’t think a sense of purpose is inherently fulfilled or disappointed by a PhD program. There are too many variables.

However, if you’re counting on a PhD program to give you a sense of purpose, I’d be very careful. I’d be even more cautious if purpose for you means “tenure-track professor.” Think broadly about what success means to you and keep an open mind .

5. Is my discipline in demand?

Okay, so you need to know that different disciplines have different experiences. Silicon Valley has fallen in love with some PhDs, and we’re seeing “PhD required” or “PhD preferred” on more and more job postings. So if your PhD is in certain, in-demand subjects… It can be a good decision.

My humanities PhD, on the other hand, was a mistake. I’m 5 years out now, and I’ve learned how to use it and make money with it. That’s the great news. But I’d never recommend that anyone get a PhD in the humanities. Sorry. I really wish I could. It’s usually a waste of years of your life, and you’ll need to figure out how to get a totally unrelated job after anyway.

TBH, most of the skills I make money with these days I taught myself on Skillshare .

6. Is a PhD worth it for your potential?

My guess: Absolutely

Every human being has unlimited potential, of course. But here’s the thing that really can make your PhD worth it. The PhD can amplify your potential. It gives you a global reach, it gives you a recognizable brand, and it gives you a mind like no other.

One of my heroes is Brené Brown. She’s taken research and transformed the world with it, speaking to everyone from Wall-Street leaders to blue-collar workers about vulnerability, shame, and purpose. She took her PhD and did amazing things with it.

Your potential at the end of your PhD is greater than it has ever been.

The question is, what will you do with that potential?

Many PhD students are held back, not by their potential, but by the fact that they’ve learned to believe that they’re worthless. Your potential is unlimited, but when you are beaten and exhausted, dragging out of a PhD program with barely any self-worth left, it’s very hard to reach your potential. You first need to repair your confidence.

But if you can do that, if you can nurture your confidence and your greatness every day until you begin to believe in yourself again, you can take your potential and do anything you want with it.

So why get a PhD?

Because it symbolizes your limitless potential. If you think strategically about how to put it to work.

PhD Graduates Don’t Need Resumes. They Need a Freaking Vision

By the way… Did you know I wrote a book about building a career with a PhD? You can read the first chapter for free on Amazon.

So if you’re asking me, “should I do a PhD,” I hope this post helps you. Try your best to check your emotion, and weigh the pros and cons.

And at the end of the day, I don’t think that whether a PhD is worth it or not is some fixed-in-stone thing. In fact, it depends on what you do with it.

So why not make it worth it? Work hard on yourself to transform into a leader worthy of the letters after your name, and don’t be afraid to learn how to leverage every asset the PhD gave you.

One of the reasons I took my PhD and launched my own company is that I saw how much more impact I could have and money I could be making as a consultant (perhaps eventually with a few employees). As long as I worked for someone else, I could see that my income would likely be capped. Working for myself was a good way to maximize my output and take control of my income.

It’s up to you to make it worth it. Pick what’s important to you and how the degree helps you get there, and chase it. Keep an open mind about where life will take you, but always be asking yourself how you can make more of it.

Check out the related post- 15 Good, Bad, and Awful Reasons People Go to Grad School. — I Answer the Question, “Should I Go to Grad School?” )

Consulting Secrets 3 – Landing Clients

Photo by Christian Sterk on Unsplash There’s a new type of post buzzing around LinkedIn. I confess, I’ve even made a few. The post is

You’re Not Good Enough… Yet

Last year, I spent $7k on a business coach. She was fantastic. She helped me through sessions of crafting my ideas to become a “thought

$200/hr Expert? Here’s the Secret!

Photo by David Monje on Unsplash I was listening to Tony Robbins this week. He was talking about being the best. Tony asks the audience,

SHARE THIS:

EMAIL UPDATES

Weekly articles, tips, and career advice

Roostervane exists to help you launch a career, find your purpose, and grow your influence

- Write for Us

Terms of Use | Privacy | Affiliate Disclaimer

©2022 All rights reserved

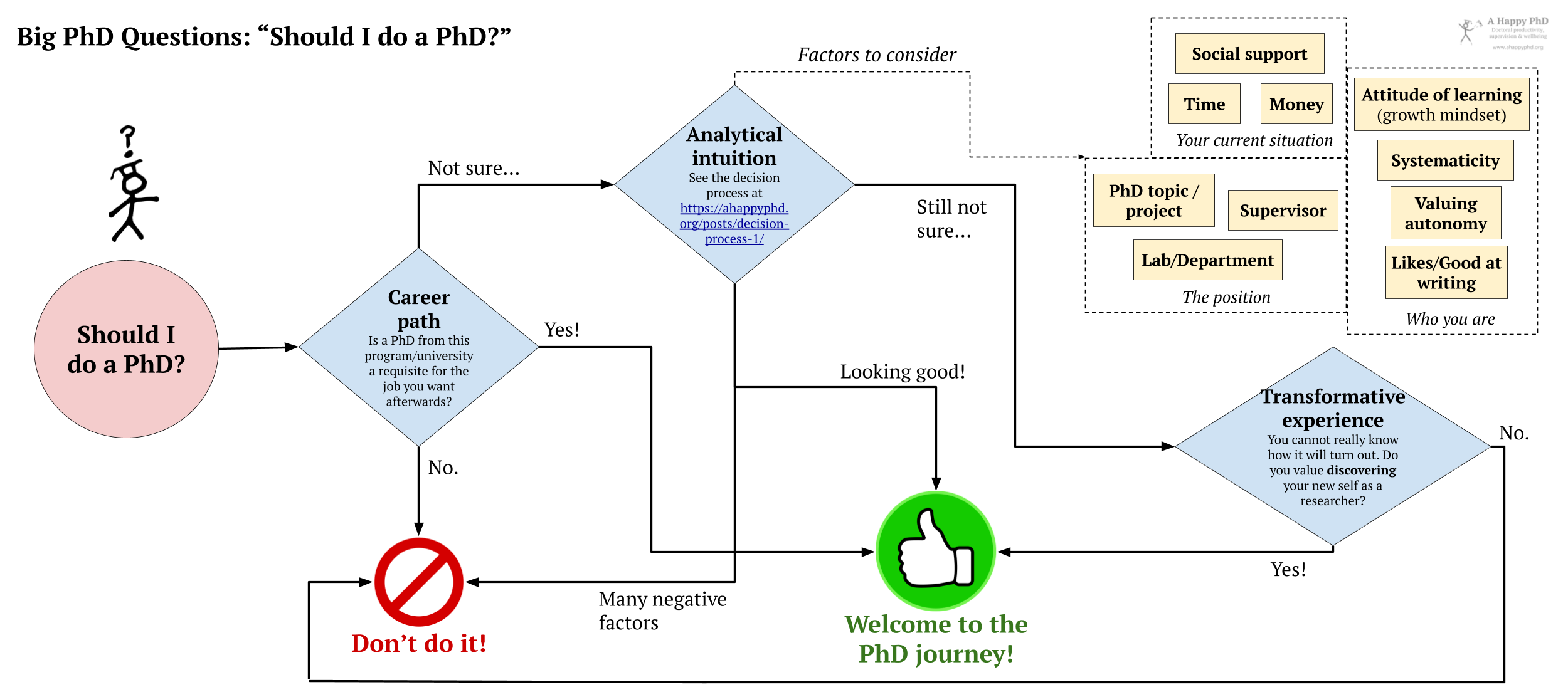

Big PhD questions: Should I do a PhD?

If you are reading this, chances are that you have already decided to do a PhD. Yet, you may know someone who is considering a doctoral degree (or you may be offering such a position as a supervisor to prospective students). This post is for them . In this new type of post, we will look at big questions facing any PhD student. Today, we analyze the question that precedes all the other big PhD questions: “should I do a PhD?”. Below, I offer a couple of quick, simple ways to look at this important life decision, and a list of 10 factors to consider when offered (or seeking) a PhD position.

The other day, some researcher colleagues told me about a brilliant master student of theirs, to whom they were offering the possibility of doing a PhD in their lab. However, the student was doubtful: should she embark on this long and uncertain journey, on a low income, foregoing higher salaries (and maybe more stability) if she entered the job market right away? Her family and friends, not really knowing what a PhD or academia are like, were also giving all sorts of (sometimes contradictory) advice. Should she do a PhD?

This simple question is not asked nearly as much (or as seriously) as it should. Many people (myself included!) have embarked on this challenging, marathon-like experience without a clear idea of why it is the right choice for them, for that particular moment in their lives. Given this lack of clarity, we shouldn’t be surprised by the high rates of people that drop out of doctoral programs , or that develop mental health issues , once they hit the hard parts of the journey.

So, let’s approach this big PhD question from a few different angles…

A first short answer: Thinking about the career path

When I started my PhD back in 2007, coming from a job in the industry, I only had a very nebulous idea that I might like to do research professionally (albeit, to be honest, what I liked most about research was the travelling and the working with foreign, smart people). My employer back then was encouraging us to earn doctoral degrees as a way to pump up the R&D output. Thus I started a PhD, without a clear idea of a topic, of who would be my supervisor, or what I would do with my life once I had the doctoral degree in my hands.

This is exactly what some career advice experts like Cal Newport say you should NOT do . They argue that graduate degrees (also including Master’s) should not be pursued due to a generic idea that having them will improve our “job prospects” or “hirability”, that it will help us “land a job” more easily. Rather, they propose to take a cold, hard look to what we want to do after the doctorate (do I want to be a Professor? if so, where? do I want a job in the industry? in which company? etc.). Then, pursue the PhD only if we have proof that a PhD, from the kind of university program we can get into 1 , is a necessary requisite for that job .

If you aspire to be an academic (and maybe get tenure), do not take that aspiration lightly: such positions are becoming increasingly rare and competition for them is fiercer than ever. Take a look at the latest academic positions in your field at your target university, and who filled them. Do you have a (more or less) similar profile? In some highly prestigious institutions, you need to be some kind of “superstar” student, coming from a particular kind of university, if you want to get that kind of job.

In general, I agree with Cal that we should not generically assume that a PhD will be useful or get us a job in a particular area, unless we have hard evidence on that (especially if we want a job in the industry!). Also, I agree that the opportunity cost of a PhD should not be underestimated: if you enroll in a PhD program, you will probably be in for a reduction in salary (compared with most industry jobs), for a period of four or more years!

Yet, for some of us, the plan about what to do after the PhD may not be so clear (as it was my case back in 2007). Also, being too single-minded about what our future career path should look like has its own problems 2 . Indeed, there are plenty of examples of people that started a PhD without a clear endgame in mind, who finished it happily and went on to become successful academics or researchers. Ask any researcher you know!

So, if this first answer to ‘should I do a PhD?' did not give us a clear answer, maybe we need a different approach. Read on.

A longer answer: Factors for a happy (or less sucky) PhD

If we are still unsure of whether doing a PhD is a good idea, we can do worse than to follow the decision-making advice I have proposed in a previous post for big decisions during the PhD. In those posts, I describe a three-step process in which we 1) expand our understanding of the options available (not just to do or not do a PhD, but also what PhD places are available, what are our non-PhD alternative paths, etc.); 2) analyze (and maybe prototype) and visualize the different options; and 3) take the decision and move on with it.

However, one obstacle we may face when applying that process to this particular decision is the “analytic intuition” step , in which we evaluate explicitly different aspects of each of the options, to inform our final, intuitive (i.e., “gut feeling”) decision. If we have never done a PhD or been in academia, we may be baffled about what are the most important aspects to consider when making such an evaluation about a particular PhD position, or whether a PhD is a good path for us at all.

Below, I outline ten factors that I have observed are related to better, happier (but not necessarily stress-free!) PhD processes and outcomes. Contrary to many other posts in this blog (where I focus on the factors that we have control over ), most of the items below are factors outside our direct control as PhD students, or which are hard to change all by ourselves. Things like our current life situation, what kind of person we are, or the particular supervisor/lab/topic where we would do the PhD. Such external or hard-to-change aspects are often the ones that produce most frustration (and probably lead to bad mental health or dropout outcomes) once we are on the PhD journey:

- Time . This is pretty obvious, but often overlooked. Do we have time in our days to actually do a PhD (or can we make enough time by stopping other things we currently do)? PhD programs are calibrated to take 3-4 years to complete, working at least 8 hours a day. And the sheer amount of hours spent working on thesis materials seems to be the most noticeable predictor of everyday progress in the PhD , according to (still unpublished) studies we are doing of doctoral student diaries and self-tracking (and, let’s remember, progress itself is the most important factor in completing a PhD 3 ). And there is also the issue of our mental energy : if we think that we can solve the kind of cognitively demanding tasks that a PhD entails, after 8 hours of an unrelated (and potentially stressful) day job, maybe we should think again. Abandon the idea that you can do a PhD (and actually enjoy it) while juggling two other day jobs and taking care of small kids. Paraphrasing one of my mentors, “a PhD is not a hobby”, it is a full-time job! Ignore this advice at your own risk.

- Money . This is related to the previous one (since time is money, as they say), but deserves independent evaluation. How are we going to support ourselves economically during the 3+ years that a PhD lasts? In many countries, there exist PhD positions that pay a salary (if we can get access to those). Is that salary high enough to support us (and maybe our family, depending on our situation) during those years? If we do not have access to these paid PhD positions (or the salary is too low for our needs), how will we be supported? Do we have enough savings to keep us going for the length of the PhD? can our spouse or our family support us? If we plan on taking/keeping an unrelated job for such economic support, read again point #1. Also, consider the obligations that a particular paid PhD position has: sometimes it requires us to work on a particular research project (which may or may not be related to our PhD topic), sometimes it requires us to teach at the university (which does not help us advance in our dissertation), etc. As stated in the decision process advice , it is important to talk to people currently in that kind of position or situation, to see how they actually spend their time (e.g., are they so stressed by the teaching load that they do not have time to advance in the dissertation?).

- Having social support (especially, outside academia). This one is also quite obvious, but bears mentioning anyways. Having strong social ties is one of the most important correlates of good mental health in the doctorate , and probably also helps us across the rough patches of the PhD journey towards completion. Having a supportive spouse, family, or close friends to whom we can turn when things are bad, or with whom we can go on holidays or simply unwind and disconnect from our PhD work from time to time, will be invaluable. Even having kids is associated with lower risk of mental health symptoms during the doctorate (which is somewhat counter-intuitive, and probably depends on whether you have access to childcare or not). A PhD can be a very lonely job sometimes, and there is plenty of research showing that loneliness is bad for our mental and physical health!

- An attitude of learning . Although this is a somewhat squishy factor, it is probably the first that came to my mind, stemming from my own (anecdotal, non-scientific) observation of PhD students in different labs and universities. Those that were excited to learn new things, to read the latest papers on a topic, to try a new methodology, seem to be more successful at doing the PhD (and look happier to me). People that are strong in curiosity seem a good match for a scientific career, which is in the end about answering questions (even if curiosity also has its downsides ). This personal quality can also be related to Dweck’s growth mindset (the belief that our intelligence and talents are not fixed and can be learned) 4 . If you are curious , this mindset can be measured in a variety of ways .

- A knack for systematicity and concentration. This one is, in a sense, the counterweight to the previous one. Curious people often have shorter attention spans, so sometimes they ( we , I should say) have trouble concentrating or focusing on the same thing for a long period of time. Yet, research is all about following a particular method in a systematic and consistent way, and often requires long periods of focus and concentration. Thus, if we find ourselves having trouble with staying with one task, idea or project for more than a few minutes in a row, we may be in for trouble. The PhD requires to pursue a single idea for years !

- Valuing autonomy . As I mentioned in passing above, a PhD is, by definition, an individual achievement (even if a lot of research today requires teamwork and collaboration). Thus, to be successful (and even enjoy) the process of the PhD, we have to be comfortable being and working alone, at least for some of the time. Spending years developing our own contribution to knowledge that no one else has come up with before, should not feel like a weird notion to us. Even if it occasionally comes with the uncomfortable uncertainty of not knowing whether our ideas will work out. In human values research they call this impulse to define our own direction, autonomy 5 , and many of my researcher friends tell me it is a very common trait in researchers. However, these values are very personal and very cultural. To evaluate this factor, we could simply ask ourselves how much we value this autonomy over other things in life, or use validated instruments to measure relative value importance, like the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) .

- Liking and/or being good at writing . I have written quite a bit here about the importance (and difficulty) of writing in the PhD . Be it writing journal and conference papers, or the dissertation tome itself, every PhD student spends quite a bit of time writing, as a way of conveying new knowledge in a clear, concise and systematic way. Learning to write effectively is also known to be one of the common difficulties of many PhD processes 6 , due to reasons discussed elsewhere . Hence, if we hate writing, we should think carefully about spending the next 3+ years doing something that necessarily involves quite a bit of writing, other people spotting flaws in your writing, and rewriting your ideas multiple times. Please note that I don’t consider being a good (academic or nonfiction) writer a necessary requisite for a PhD, as it can be learned like any other skill (again, the learning attitude in point #4 will help with that!). But being good at it will certainly make things easier and will let you focus on the content of the research, rather than on learning this new, complex skill.

- Compatibility (or, as they call it in the literature sometimes, the “fit”) of our and their personalities, ways of working (e.g., do they like micro-managing people, but you hate people looking over your shoulder?) and expectations about what a doctoral student and a supervisor should do.

- A concern for you as a person. Since this is difficult to evaluate as we may not know each other yet, we could use their concern about the people that work in their lab (beyond being just a source of cheap labor), as a proxy.

- Enthusiasm for the field of research or topic, its importance in the world, etc. A cynic, jaded researcher may not be the best person to guide us to be a great member of the scientific community.

- A supervisor that is well-known, an expert in the particular topic of the dissertation. Looking at the number of citations, e.g., in Google Scholar is a good initial indicator, but look at the publication titles (are they in similar topics to those they are offering you as your doctoral project? if not, that may mean that this person may also be new to your particular dissertation topic!).

- Related to the previous one, does this researcher have a good network of (international) contacts in other institutions? Do they frequently co-author papers with researchers in other labs/countries? We may be able to benefit from such contact network, and get wind of important opportunities during the dissertation and for our long-term research career.

- Openness (and time!) to talk about what the doctoral student job entails, potential barriers and difficulties , etc. This can be a proxy to both their general busyness (you will not get much guidance if they can never meet you because they have too little time) and their communication skills (something critical to consider when signing up to work closely with someone for years).

- Whether the supervisor is an ethical person. This is very important but seldom considered (maybe because it is hard to evaluate!). For sure, we don’t want to be backstabbed or exploited by our supervisor!

- Whether this person(s) is known to be a good supervisor . Have they already supervised other doctoral students to completion, in nominal time and with good grades? Do they regularly attend trainings and professional development about doctoral supervision? Do they seem to care about this part of their job for its own sake (rather than as a mere medium to get cheap labor)?

- You may be wondering how you are going to gather information about all the aspects mentioned above. Sometimes you can ask the supervisor directly, but you can also talk with current PhD students of this person, or students in the same lab/department (but do not take what they say at face value: partisanship, gossip or rivalries may be at work!). If you have the time and the opportunity, try to “prototype” (see the decision process post) the experience of working with this supervisor: do a master thesis with them, or a summer internship, or use the work on a joint PhD project proposal (a pre-requisite before being accepted as a doctoral student in some institutions). Some things we don’t know we like until we try them!

- Of course, all of the above are two-way streets. As prospective students, we also need to show to a potential supervisor that we are open to talk about expectations, that we are somewhat flexible, dependable, etc. Be very conscious of this in your interactions with supervisors and other people in their lab!

- The lab/department where you will do the dissertation . Again, there are many things to consider here. Is there an actual research group, or will we be doing our research in isolation with our supervisor? Normally, the former is preferable, since that gives us more resources to draw from if the supervisor is not available. Is the research group well known in the field (again, look at citations, invited talks, etc. of different group members)? But especially, try to get an idea of the lab’s working atmosphere : is it stressful, relaxed, collaborative, competitive…? As with the previous point, we could prototype it by spending some time working there, or we can interview one or more people working in the lab. If we do the latter, it is better to go beyond direct questions that will give vague (and maybe unreliable) answers, like “it’s good”. Rather, take a journalistic approach, and ask people to narrate concretely what the routines are in the lab, when and how did they last collaborate with another student, or the last conflict arising in the lab. Then, decide whether this kind of ambience is a good fit for you .

- The concrete PhD topic . We should find out (e.g., from our prospective supervisor) whether the topic of the dissertation is already well-defined, or rather we will have to explore and define it ourselves (both options have pros and cons, and again it depends whether we value more autonomy and exploration, or having a clear path ahead). Is the area or keywords of the PhD topic going up or down in popularity (see here for a potential way to find out)? Are there clear funding schemes that specifically target this kind of research topic, at the national or international level? How easy is it to collect evidence for this kind of research (empirical data is a critical element in almost all research fields, so we want easy and reliable access to them)? I would not evaluate a PhD topic on the basis of whether we love it right now, as we never know much about any research area when we start a doctorate (even if we think we do!). An attitude of learning and curiosity (see #4) will take care of that. Rather, talk with the supervisor about how the research process might look like, what kind of activities will take up most of our time (reading papers? doing labwork? interviewing people?): do we find those activities interesting?

Yet, after considering all these 10 factors separately, we may not be clear on the decision (maybe some aspects are good, others not so much). If, after all this thinking and gathering of information we still are not sure, there is one last idea I can offer…

One last answer: We cannot really know (the PhD as a transformative experience)

We could also frame the question of whether to do a PhD as what philosopher L.A. Paul calls a “transformative experience” 8 . Doing a PhD is a big life decision (like becoming a parent or taking a powerful drug) through which we probably will transform ourselves into another person , with different preferences and even different values.

I can think of many ways in which I am a different person now, due to the transformative experience of doing my PhD: I am now able to read and understand scientific papers (e.g., when I come across a new idea or “expert”, I go and read actual research papers about that), and I can evaluate the reliability of different types of evidence; I trust more scientific advances and consensus; I am more comfortable speaking (and writing) in English; I am more aware of culture and life in other countries, and I have less chauvinistic views of foreigners (due to my international experience gained as a researcher). Et cetera .

Paul’s argument regarding transformative experiences is that there are limitations to simulating (i.e., imagining) whether we will like the experience, as our own values and preferences may be changed by the very experience we try to simulate. For similar reasons, there are limits to the usefulness of asking others about the decision (and trusting their testimony), since they also have different values, preferences and coping strategies than us. Even looking at the latest and most reliable research on the topic (e.g., whether PhD students end up happier and/or more satisfied with their lives than people who did not take that choice) is of limited help, since such research (of which there is little!) often concentrates on average effects, and we may not be “average”.

What to do, then?

L.A. Paul’s way out of this dilemma seems to be a reframe of the question: "Will I be happier if I do a Ph?“ , "Should I do a PhD?“ . Rather, we can ask: “Do I value discovering my new self as a researcher/doctor?" . In a sense, this new question targets a key intrinsic value we may (or may not) have: Do we appreciate learning, exploring, getting novel experiences, discovering and remaking ourselves (related to point #4 above)? If yes, a PhD might be a good idea. If we prefer stability, things (and our life) as they have always been, the status quo … maybe we will not appreciate this transformation that much.

There is no right or wrong answer. Only your answer.

The diagram below summarizes the main ideas in this post. Reflect upon these questions, and make your own choice. Take responsibility for your choice… but don’t blame yourself for the outcome , i.e., if it does not work out as you expected. There are too many inherent uncertainties about this decision that cannot be known until we actually walk the path.

Summary of the ideas in this post

Did these arguments and factors help you think through the decision of doing (or not doing) a PhD? What did you decide in the end and why? I’d be very curious to know… Let us know in the comments section below!

Header photo by Zeevveez

This seems especially important in the U.S. higher education and research market, which is quite clearly stratified, with research-focused and more teaching-focused universities, “Ivy Leagues”, etc. ↩︎

If we get obsessed with going a particular way and we fail to achieve it (or even if we achieve it and find out that it’s not what we thought it’d be), we may end up feeling stuck and/or depressed. See Burnett, W., & Evans, D. J. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life , for ideas on how to get “unstuck” in those cases. ↩︎

De Clercq, M., Frenay, M., Azzi, A., Klein, O., & Galand, B. (2021). All you need is self-determination: Investigation of PhD students’ motivation profiles and their impact on the doctoral completion process. International Journal of Doctoral Studies , 16 , 189–209. ↩︎

Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 113 (31), 8664–8668. ↩︎

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture , 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116 ↩︎

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N. C., McAlpine, L., & Hubbard, K. (2018). The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students’ completion, achievement, and well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies , 13 , 361–388. https://doi.org/10.28945/4113 ↩︎

Masek, A., & Alias, M. (2020). A review of effective doctoral supervision: What is it and how can we achieve it? Universal Journal of Educational Research , 8 (6), 2493–2500. ↩︎

Paul, L. A. (2014). Transformative experience . OUP Oxford. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.

Google Scholar profile

To Be or Not To Be a PhD Candidate, That Is the Question

Originally published in the AWIS Magazine.

By Katie Mitzelfelt, PhD Lecturer, University of Washington Tacoma AWIS Member since 2020

Choosing whether or not to work toward a PhD, and then whether or not to finish it, can be very difficult decisions―and there are no right or wrong answers.

Obtaining a PhD is a prestigious accomplishment, and the training allows you to develop your critical-thinking and innovation skills, to conduct research into solving specialized problems, and to learn to troubleshoot when things don’t go as expected. You develop a sense of resilience and a commitment to perseverance, skills which are rewarded when that one experiment finally works and when the answer to your long-sought-after question becomes clear. However, finishing a PhD involves a lot of work, time, and stress. It is mentally, physically, and psychologically exhausting.

There are other ways to hone critical thinking and problem-solving skills and many careers that do not require a PhD such as teaching, science communications, technical writing, quality control, and technician work. Opportunities exist in industries from forensics to food science and everywhere in between.

Countering the Stigma of Perceived Failure

Often we mistakenly view a student’s decision not to pursue a PhD, or to leave a PhD program, as giving up. Many academics view non-PhDs as not smart enough or strong enough to make it. But this is simply not true. In April 2021 Niba Audrey Nirmal produced a vulnerable and inspiring video on the topic of leaving graduate school, titled 10 Stories on Leaving Grad School + Why I Left , on her YouTube channel, NotesByNiba .

In making the video, she hoped to change people’s minds by naming the stigma, shame, and guilty feelings that come with leaving a PhD program. She highlights ten stories from others who either completed their PhD programs or chose to leave, and she goes on to openly share her personal reasons for ending her own doctoral studies in plant genetics at Duke University.

The people showcased in the film share the reasons behind their respective decisions to leave or to stay, as well as heartfelt advice encouraging viewers to make the decision best for them. Participant Sara Whitlock shares, “I decided to leave [my Ph.D. program] . . . but I still had to kind of disentangle myself from that piece of my identity that was all tied up in science research, and that took a long time, but once I did, I was a lot happier.”

Another participant, Dr. Sarah Derouin, states, “Everyone is going to have an opinion about what you do with your life. They’ll have an opinion if you finish your PhD; they’ll have an opinion if you don’t finish your PhD. At the end of the day, you have to realize what is best for you . . . and then make decisions based on that, not on what you think other people will think of you.” In her film, Nirmal recommends the nonprofit organization PhD Balance as a welcoming space for learning about others’ shared experiences.

A Personal Choice

So, do you need a PhD? It depends on what you want to do in your career and in your life. It also depends on your priorities―money, family, free time, fame, advancing science, curiosity, creating cures, saving the planet, etc. (Note that what you value now may shift throughout your life. Your journey will not be a straight line: every step you take will provide an experience that will shape who you are and how you view the world.)

Your decision whether or not to pursue a PhD should be based on your specific goals. Whether or not you obtain a PhD, remember that your journey is unique. The breadth of our experiences as scientists is what yields the diverse perspectives necessary to tackle the world’s difficult problems, now and in the years ahead.

The stories below, based on my own interviews, provide examples of the personal experiences and career choices of some amazing and inspiring scientists. Some of them decided to skip further graduate studies; some chose to go the whole distance on the PhD route; and still others left their doctoral programs behind.

Mai Thao, PhD, Medical Affairs, Medtronic

After completing her undergraduate degree, Dr. Thao worked in a private sector lab. She shared “work was physically exhausting, with little reward. I had no autonomy; instead, I entered a production line similar to the ones that my own parents had endured to provide a living for my family.” While the studies she was working on were important, Dr. Thao felt her contributions to those studies, were minimal. She asserts, “Being naive and a bit arrogant, I thought at that time that I was clearly made for better and greater things, so I quit right in the middle of the Great Recession [2007–2009].” She then pursued a master’s degree in chemistry from California State University, Sacramento, and went on to complete her doctorate in chemistry and biochemistry at Northern Illinois University. Dr. Thao reflects, “In retrospect, I knew that having a PhD would offer me better opportunities and ones with true autonomy.”

When asked how satisfied she is with her decision to complete the doctoral program, Dr. Thao says, “I go back and forth about being satisfied with my decision . . . I was clueless about financing college and even declined multiple schools that offered me full academic scholarships. Today I slowly chip away at my financial error. On the other side, I do have a PhD and can afford to chip away at my mountain of student loan debt. I am also fortunate to be able to really live in the present, to save for the future, and to give.”

Today, Dr. Thao is a scientific resource consultant for internal partners and external key stakeholders at Medtronic. She says, “My day-to-day can range from providing evidence from the literature to supporting scientific claims for marketing purposes. My favorite part of my job is being able to add scientific value to the projects I support. It’s always so rewarding to see how the ideas of engineers and scientists materialize and then to see how the commercial team takes it to market to make a great impact on patients, and I get to see the entire process.

Tam’ra-Kay Francis, PhD, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington

Dr. Francis currently works as a postdoctoral scholar in the chemistry department at the University of Washington. Her research examines “pedagogies and other interventions in higher education that support underrepresented students in STEM. [My] efforts engage both faculty and students in the development of equity-based environments.” She is currently investigating the impact of active learning interventions in the Chemistry Department.

Dr. Francis acknowledges that deciding to pursue a doctorate is a very personal decision. “There are so many things to consider— time, finances, focus area, committee expertise and support, and next steps,” she says. “Not every job requires a PhD, so it is important to stay informed about the expertise required for a career that you are considering.”

She provides advice to prospective graduate students, telling them to do their due diligence when seeking out programs that are right for them. “When interviewing with potential advisers, don’t be afraid to ask specific questions about things that are important to your success. Ask them about their expectations (for example, their philosophies on mentoring and work-life balance) and about the types of support they provide (for example, help with research funding, mental health, and professional development).”

She also suggests reaching out to graduate students in the groups or departments you are interested in. “Ask them directly about what the culture is like and about how they are being supported.” She wants to remind students that they do have a voice and a say in their graduate career. “Your needs will change throughout graduate school, so it is important that you find advocates, both within and outside of your institution, to champion you to the finish line. It is very important that you build your network of support as early as possible,” says Dr. Francis. She credits her adviser, mentors, committee, and former supervisors as being crucial supports in her journey.

“In the first year of my doctoral program, I found an amazing community of scholars from a research interest group (CADASE) within the National Association of Research in Science Teaching. It was a great space to find mentors and build connections in a large professional organization,” said Dr. Francis. At the institutional level, Dr. Francis served as vice president of the Graduate Student Senate and was a member of the Multicultural Graduate Student Organization. For Dr. Francis, her participation in these groups and organizations contributed to her professional growth, sense of community, and success in graduate school.

Liz Goossen, MS, Senior Marketing Specialist at Adaptive Biotechnologies

Reflecting on her decision not to pursue a doctorate, Goossen acknowledges, “I spent a lot of time in graduate school researching potential career paths one could do with a PhD, [and even organized] a career day featuring a dozen speakers from across the country in a variety of scientific fields. By the end, I felt that none of these career options would be a good fit for me (or at least not a good enough fit to warrant five or more years in my program). I worried about going through all of my twenties without starting a 401(k) or having normal working hours, and [I also worried about] all of the other trade-offs there are between finishing a PhD and joining the workforce. I lived in Salt Lake City at the time, and the job market was flooded with PhDs who were overqualified for many of the available positions. By leaving [school] with a master’s, I had more options.”

When asked if she is satisfied with her decision, Goossen says she is 99% satisfied. “There are times I encounter jobs requiring a PhD that look enticing, and [that’s when] I wonder if it may have been nice to have one, but those moments are rare.”

Maureen Kennedy, PhD, Assistant Professor, University of Washington Tacoma

Dr. Kennedy shares that a major factor in her decision to complete a doctorate was the financial support she received. She says, “I was able to maintain funding through research agreements and occasional teaching opportunities that I loved! This consistent funding allowed me to enjoy the freedom of pursuing my PhD on research I found very fulfilling, while also gaining valuable teaching experience. I always felt at home in an academic setting and was happy to stay there while being supported.”

Dr. Kennedy reports being very satisfied with her decision to pursue a doctorate and attributes this satisfaction to knowing that she is making “an impact, both through teaching new generations of students and through being able to continue to pursue [her] favored research topics.” She reflects on some of the positive and negative impacts of her decision: “As a PhD, I am able to direct my own research agenda with relative independence. One major trade-off is that by pursuing an academic career, my salary is likely less than I could get in the private sector with the same skills. My lifetime cumulative salary will also likely be less, due to the years living off of research and teaching stipends, rather than [benefiting from] full-time employment and salary. Also, my years spent as a research scientist funded by soft money, or periodic research grants, were often uncertain; when one grant was winding down, [I had to pursue] new grants.”

Dr. Kennedy remarks that as a tenure-track professor, she has diverse daily activities, which she finds appealing. She shares, “Some days are focused on teaching (particularly during the academic year), some days on research (particularly during the summer), and some days I am able to do both. Before the pandemic, I would come to campus several days a week, but I was also able to work from home on other days. Days are often filled with lectures and office hours, or meetings with research collaborators. I carve out times to focus on reading and writing when I can and when deadlines are approaching. It is definitely a balancing act of time management and of planning, to ensure I am able to fulfill my teaching and research commitments.”

Dr. Kennedy advises that a doctorate “is a long-term commitment. If your goal (or passion!) is a lifetime of leading independent research (with or without teaching), a PhD will help to broaden your available opportunities and will open doors for you.” She cautions that a PhD can “delay your career trajectory and salary growth,” and so she suggests that you carefully research career opportunities and requirements to see whether a doctorate makes sense for you.

Olivia Shan, BS, Restoration Coordinator at Palouse–Clearwater Environmental Institute

Shan attributes her decision not to pursue a graduate degree to cost, lack of time, and uncertainty about what to focus on. She remarks that at some point, she may decide to continue her education, but only if she receives full funding to pay for it. She says she is very satisfied with her decision to enter the workforce right after finishing her undergraduate studies. “After earning my bachelor’s, I worked as a wildland firefighter [and] did [other] jobs I found fun,” says Shan. “Not having any debt after college gave me the flexibility to do what I desired and to explore options. I am all for taking a break from academia and for actually trying out jobs before [narrowing your] focus too far. It would have been a real bummer to spend years on [graduate work I thought I was interested in pursuing] and then later to realize that [this] was not at all what I wanted to do.”

Shan shares that she “adore[s] the diversity of [her] job, and the feeling that [she] is truly helping the environment [and her] community.” She encourages others: “Follow your heart, because you can make a difference no matter your education level. It all comes down to passion, drive, and work ethic!”

Morgan Heinz, MS, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Washington Tacoma

After completing his master’s degree, Heinz began applying to PhD programs, using the network and interests he had already developed in his previous graduate studies. He could not yet see any other paths for himself. He also wanted to teach college courses and saw the doctorate as the only way to accomplish this goal.

He called and emailed students in the lab to ask them what the environment is like. He received very candid responses and ruled out some labs as a result.

Once he started the PhD program, Heinz found that his doctoral adviser was much more hands-off than his master’s adviser had been and required an unexpected level of independence. This less-directed environment was difficult for Heinz to thrive in. He acknowledges, “I did not have the skill of looking at where the science is, looking for gaps, and seeing how I could contribute.”

These early stages of the PhD process helped him crystallize his passions. He realized that he loves learning and teaching, but he didn’t like synthesizing the literature and determining the next question to ask.

Heinz ultimately decided to take a short hiatus from the doctoral program and taught classes. This interlude reaffirmed his passion for teaching and helped him decide to leave his graduate studies behind.

When he first decided to leave the program, he felt like he was giving up, was worthless, and was a failure. Through continued reflection, he realized, “the side routes that I have taken have actually made me stronger as an instructor.”

After leaving the PhD program, Heinz participated in a community college faculty training program and was hired before even finishing it. He says that the community college allowed anyone to enroll, which was philosophically satisfying and emotionally fulfilling, enabling him to offer an education to any student who wanted it. Heinz tries to impress upon his students that there are a lot of different paths in life. He states, “I don’t have a PhD, and I am exactly where I want to be.”

If you are considering a PhD or masters program, Heinz suggests looking to see if they offer health insurance and mental health services — because graduate school can be stressful and depressing. Many programs may even pay a stipend for you to attend. Heinz also advises, “Don’t be afraid to change your mind. Draw some boundaries.”

Finally, Heinz adds, “Don’t be apologetic about the things that you’re interested in and are excited about, even when people tell you that that’s not an arena for you, because of how you look or who you are. If you’re interested in it, then that’s yours, and you can own it. You don’t need a PhD to validate that interest. You don’t need a PhD to prove your worth in that field. Life is too short to not pursue the things that excite you.”

There Are No Wrong Answers

Whatever decision you make, know that it is the right one for you in the here and now. You may grapple with disappointment or frustration along the way, but regret will not help move you forward. Be grateful for your journey and for how it helps you grow.

Listen to stories and advice, but make the choices that feel right for you. Your story is not the same as anyone else’s. What is right for them, may not be right for you. Be the author of your own life. Your story is beautiful, and you are worthy of living it.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Niba Audrey Nirmal, Multimedia Producer & Science Communicator, NotesByNiba, and to Brianna Barbu, Assistant Editor, C&EN, for their thoughtful edits and suggestions on this article.

Dr. Katie Mitzelfelt is currently a biology lecturer at the University of Washington Tacoma. She received her PhD in biochemistry from the University of Utah and researched cardiac regeneration as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington Seattle, prior to transitioning to teaching. She identifies as an educator, content designer, writer, scientist, small business owner, and mom

Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits .

- 1629 K Street NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20006

- (202) 827-9798

Registered 501(c)(3). EIN: 23-7221574

Quick Links

Join AWIS Donate Career Center The Nucleus Advertising

Let's Connect

PRIVACY POLICY – TERMS OF USE

© 2024 Association for Women in Science. All Rights Reserved.

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_contact_form admin_label=”Contact Form” captcha=”off” email=”[email protected]” title=”Download Partner Offerings” use_redirect=”on” redirect_url=”https://awis.org/corporate-packages/” input_border_radius=”0″ use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” custom_button=”off” button_letter_spacing=”0″ button_use_icon=”default” button_icon_placement=”right” button_on_hover=”on” button_letter_spacing_hover=”0″ success_message=” “]

[et_pb_contact_field field_title=”Name” field_type=”input” field_id=”Name” required_mark=”on” fullwidth_field=”off”]

[/et_pb_contact_field][et_pb_contact_field field_title=”Email Address” field_type=”email” field_id=”Email” required_mark=”on” fullwidth_field=”off”]

[/et_pb_contact_field]

[/et_pb_contact_form][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[box type=”download”] Content goes here[/box]

Complimentary membership for all qualified undergraduates/graduates of the institution. Each will receive:

• On-line access to the award-winning AWIS Magazine (published quarterly)

• Receipt of the Washington Wire newsletter which provides career advice and funding opportunities

• Ability to participate in AWIS webinars (both live and on-demand) focused on career and leadership development

• Network of AWIS members and the ability to make valuable connections at both the local and national levels

Up to 7 complimentary memberships for administrators, faculty, and staff. Each will receive:

• A copy of the award-winning AWIS Magazine (published quarterly)

• 24 Issues of the Washington Wire newsletter which provides career advice and funding opportunities

• Access to AWIS webinars (both live and on-demand) focused on career and leadership development

College Reality Check

Are PhDs Worth It Anymore? Should You Do It?

A bachelor’s degree can make you earn more money than someone whose highest educational attainment is a high school diploma or an associate degree.

On the other hand, a master’s degree can make you make even more. And if that’s not enough, you can consider getting a PhD, although it’s something that you will have to work hard for.

PhDs are worth it for individuals willing to devote resources to the attainment of the degree that can make them experts in specific fields and open doors to more career opportunities and higher salary potential. This is especially true for those who want to pursue a career in academia or research.

Continue reading if you are thinking about enrolling in a Ph.D. program.

Below, I will try to answer as many pressing questions as you probably have in your mind about getting a PhD, thus allowing you to determine whether you should give it a go or go get employed instead.

Why Should You Do a PhD?

Getting a PhD allows one to enjoy broader career opportunities where having the highest academic degree is an advantage. Naturally, a PhD paves the way to greater earning potential. Typically, individuals who do a PhD wish to reach their full capabilities, become experts in their chosen fields and make a difference.

Let’s get one thing clear: a PhD is an academic degree that takes a lot of time and money to get.

Individuals who are PhD holders, because of this, are quite rare . As a matter of fact, in the US, only around 1.2% of the entire population has a PhD — and this is why they are considered valuable.

While it’s true that completing a PhD program requires a lot of money and hard work as well as can cause stress, anxiety and many sleepless nights, it’s not uncommon for some students to still dedicate much of their resources to earning a PhD. It’s because the returns in terms of career opportunities, earnings and prestige are all worth the commitment.

What are Reasons Not to Do a PhD?

Expensive, time-consuming, requires lots of work, can cause psychological distress — these are some of the disadvantages of getting a PhD. Individuals who are not financially stable, don’t like working for several hours a week and are not fully invested in a discipline should think twice before working on a PhD.

Although there are lots of reasons for you to get your hands on a PhD, there are also some that may keep you from considering applying to a PhD program.

Leading the list is the exorbitant cost — in a few, I will talk about just how expensive a PhD is, so don’t stop reading now. And then there’s also the fact that it can take twice as long to earn a PhD than a bachelor’s degree. Typically, a PhD program can take anywhere from 4 to 5 years to complete. But for many, it can take up to 8 long years!

How long it will take for you to earn a PhD all depends on the program’s curriculum rigor and requirements.

When deciding whether or not you should push through with your plan on getting a PhD, carefully weigh the pros and cons. Dropping out somewhere in the middle of your studies can result in the wastage of both time and money.

How Many Hours Do PhD Students Study?

The vast majority of Ph.D. students spend anywhere from 35 to 40 hours per week studying and completing coursework tasks. In many instances, around 20 hours per week go to lab time or assistantship. As a result of this, enrolling in a Ph.D. program is said to be similar to having a full-time 9-to-5 job.

Undergraduate students are typically encouraged to devote 15 to 20 hours of their time per week studying in order to get good grades — for a final exam, 20 to 30 hours per week is recommended.

Since a PhD is harder, students should study twice as long (or longer) as when they were undergraduates.

During some of the busiest periods in a PhD program, such as when one is writing a dissertation, working substantially longer hours may be warranted. While a timely completion of the coursework and other tasks is obligated, however, students are free to manage their time in a way that goes with their preferences and lifestyles.

Part-time PhD students, by the way, usually work around 17.5 hours per week.

Can Students Work While Earning Their PhDs?

Although challenging, it’s possible for students to work while enrolled in a PhD program. Many working PhD students teach undergraduates at their respective universities. Some are full-time PhD students with part-time work, while others are part-time PhD students with full-time work.

First things first: earning a PhD can be hard and working on a PhD while employed can be harder. But it’s completely doable, particularly with excellent planning and time management.

As mentioned, teaching at a university is one of the most common jobs among working PhD students. But there are many other jobs available for them on and outside of the campus. Some of them are part-time jobs, while others are full-time jobs. Some have contractual work, while others take on more permanent workforce roles.

You can be a full-time employee and a part-time PhD student for better juggling of roles. But just make sure that you will be able to complete your studies within a certain period if such is a requirement at your university.

Do PhD Students Have a Social Life?

PhD students, despite all the rigorous academic and research activities they do, can have a social life. They can socialize with the members of their research group and meet new people during departmental parties and public engagement events. PhD students also have the freedom to manage their own schedule.

Everyone knows that a PhD is the highest level of degree that students can obtain. And it’s also no secret that earning a PhD is associated with a lot of time, stress and anxiety.

It’s a good thing that it’s still very much possible for you to have a social life while working on a PhD.

One of the reasons for such is that PhD students are usually allowed to follow their own schedule for as long as they get the work done. Paired with great time-management skills, you can have room to go out with friends and make new ones. Besides, there are plenty of activities PhD students attend where they can mingle with others.

However, there’s no denying that enjoying a social life can be challenging for PhD students who have to work, too. And, in some instances, one of the two tasks may fail to get ample focus and attention.

Do I Need a Bachelor’s and a Master’s to Get a PhD?

Many PhD programs require a master’s degree. However, there are some where a previously earned master’s degree is not a prerequisite. So, in other words, one may apply straight from a bachelor’s program. In some cases, however, completing a master’s program even if not a requirement can come with benefits.

Saving both time and money — arguably, this is the biggest benefit to have for completing a PhD without a master’s. And then there’s also the fact that you can flex your degree and earn money ASAP.

While there are perks that come with earning a PhD without a master’s, there are some downsides, too.

In some industries, for instance, candidates with both a master’s and a PhD may enjoy an advantage in both employability and salary potential, too. In addition, a prior master’s degree can help you decide much better on the path of your PhD studies and research for a more satisfying and fulfilling outcome.

But keep in mind that while a university may admit applicants to a PhD program without a master’s degree, it may require top-notch and impressive performance in an undergraduate program in exchange for an acceptance letter.

What are Integrated PhDs?

An integrated PhD is a combination of the taught study of a master’s program and the research element of a PhD program. It can take anywhere from 4 to 5 years to complete, depending on the program. At some universities, an integrated PhD degree is commonly referred to as an integrated master’s degree.

Earlier, we talked about the fact that you can work on a PhD without a prior master’s degree.

If the PhD requires a master’s degree or you want to earn one before applying to a PhD program, you may consider what’s referred to as an integrated PhD. As the name suggests, it’s a PhD with a master’s degree integrated into it.

Typically, a traditional PhD takes anywhere from 4 to 6 years to complete. On the other hand, an integrated PhD can take 4 to 5 years to complete — the first 1 to 2 years are for studying the master’s course and the remaining ones are for the completion of the PhD course.

But since an integrated PhD is relatively new, not too many universities offer it.

What are the Easiest PhDs to Get?

Although all PhDs require a lot of time and hard work, some are easier to obtain than the rest because of either lighter coursework and other program requirements or a shorter completion time or both. Many of the easiest PhDs to earn are available online, but only for students with the appropriate learning style.

Naturally, some of the easiest PhDs are those without dissertations, which can take 1 to 2 years to write, not to mention that most PhD students spend a couple of years conducting research and reviewing literature.

The following are some examples of Ph.D. programs minus any dissertation:

- Adult and career education

- Business administration

- Criminal justice

- Educational administration

- Grief counseling

- Human resources

- Information technology

- Nursing practice

- Public administration

- Social work

But keep in mind that different universities may have different PhD completion requirements.

Of all the easiest PhD programs, the general consensus is that most can be found online. But if you are like some students who find online learning more difficult than traditional learning, earning one can still be hard.

What are the Hardest PhDs to Get?

Some PhD programs are longer to complete and involve a lot of complex coursework and other completion requirements, thus making them some of the hardest to earn. Just like among various bachelor’s degrees, some of the most challenging PhDs to earn include those in the STEM- and healthcare-related fields.

In most instances and for most students, a PhD is harder to earn than a master’s degree. And, needless to say, it’s so much harder to obtain than a bachelor’s degree.

But some PhDs are simply more challenging to get than other PhDs.

Just like what’s mentioned earlier, STEM PhD programs are some of the hardest. Many agree that the likes of pure mathematics, theoretical physics, aerospace engineering, chemical engineering and computer science can prove to be so taxing. The same is true for healthcare PhD programs such as pharmacy, nursing and optometry.

Are PhDs Expensive?

The cost of enrolling in a PhD program amounts to $28,000 to $40,000 per year. So, in other words, a full PhD can cost anywhere from $112,000 to $200,000 or up to $320,000 (8 years). Tuition and living expenses are the primary costs of a PhD. There are ways PhD students can get funding for their studies.

Other than time, a PhD can also take up lots of money. Certain factors can impact just how much you will have to spend to get your hands on a PhD, and some of them include the university, program and length of completion.

But did you know that many PhD students don’t have to pay full price?

Because of the steep cost, it’s not uncommon for those who are enrolled in PhD programs to fund their studies through things such as studentships, research council grants, postgraduate loans and employer funding. As a matter of fact, some of them do not pay for their PhD programs — they are, instead, paid to take them.

And just like what we talked about earlier, it’s very much possible for you to be a PhD student and an employee, whether part-time or full-time, at the same time in order to earn money and fund your postgraduate studies.

Is a PhD Worth It Financially?

Without careful planning, completing a PhD program can hurt one’s finances. And if the return on investment (ROI) isn’t that substantial, it can be a waste of resources, too. For many, however, earning a PhD to secure their dream jobs or follow their true callings makes all the financial and time investments worth it.

After discussing just how much a PhD costs, it’s time to talk about if investing in it financially is a good idea.

It’s no secret that, generally speaking, the higher the educational attainment, the higher the earnings. True enough, the median weekly earning of a PhD holder is $1,909.

Doing the math, that’s equivalent to about $99,268 per year. On the other hand, the median weekly earning of a master’s degree holder is $1,574 or $81,848 per year — that’s a difference of $17,420 per year. Please keep in mind that it’s not uncommon for some master’s degree holders to make more than PhD holders.

The difference, however, becomes substantial when the average salary of bachelor’s degree holders is taken into account: $1,334 per week or $69,368 per year, which is $29,882 lower than the annual salary of those with PhDs.

Let’s take a look at the estimated annual median earnings of some PhD holders in some disciplines:

- Engineering: $107,000

- Mathematics: $104,000

- Healthcare: $98,000

- Business: $94,000

- Social science: $90,000

- Physical science: $89,000

- Public policy: $84,000

- Agriculture: $83,000

- Social work: $78,000

- Architecture: $73,000

- Communications: $72,000

Are PhDs in Demand?

PhDs are especially in demand in areas where highly specialized and very high-level research skills are important. Some of the most sought-after PhDs are those in STEM- and healthcare-related fields such as information systems, environmental engineering, chemistry, nursing and physical therapy.

As a general rule of thumb, some of the hardest PhDs to earn tend to be the most in-demand, too.

Simply put, PhDs in disciplines required for a better understanding of currently existing knowledge and challenges, development of modern-day technologies and discovery of new life-changing stuff are highly employable.

And this is why industries such as scientific research and development, manufacturing, health and social work are on the lookout all the time for promising PhD holders. Areas where PhDs are also commonly required include the education sector as well as various segments of the business industry.

Numerous transferable skills learned and developed by students, many of which are appreciated by employers across various industries, also help those with PhDs have increased job market value.

Just Before You Get a PhD

Does getting a PhD still sound great after everything you have read above? Then the smartest step for you to take next is to find the right PhD program for you and apply to it.

But keep in mind that while there are many perks that come with being a PhD holder, there are some sacrifices you will have to make before you get your hands on the prestigious academic degree. But by working hard and staying committed, it won’t take long before you are one of the country’s highest-paid and most satisfied professionals!

I graduated with BA in Nursing and $36,000 in student loan debt from the UCF. After a decade in the workforce, I went back to school to obtain my MBA from UMGC.

Similar Posts

What is a Doctorate Degree?

Writing Course

Why you (probably) shouldn’t do a phd.

- by James Hayton, PhD

- December 13th, 2021

How to write your PhD thesis (Online course starts 6th November)

An easy way to update your literature review quickly, how to cope with a problematic phd supervisor.

For most people, doing a PhD is a terrible idea.

Now I’m not saying that nobody should do a PhD- for some people it’s exactly the right path and I strongly believe in the value of academic research. But a lot of PhD students do it for the wrong reasons, without really understanding what they’re getting into, and they suffer as a result.

Why is a PhD a bad idea for most people?

It’s badly paid (if you get paid at all), or extremely expensive if you have to fund yourself. There’s also the potential lost earnings if you choose to do a PhD instead of entering the workforce.

You might think that it’s worth it, because having a PhD could open up the path to your dream job in academia, but there are far more students graduating with PhDs than the number of academic jobs available. Many PhD graduates struggle to find a permanent position, instead wandering from one temporary postdoc to another (often having to move cities or countries in the process). The stress from the lack of job security is multiplied if you’re one half of an academic couple.

Maybe you don’t want to be an academic, but you think getting a PhD will increase your value to an employer later, but unless you’re seeking research jobs or you’ve built up a set of other skills that are of value to an employer, you could find yourself in the awkward position of being both over-qualified and under-experienced for many jobs once you graduate.

This is, of course, assuming that you do graduate. In an undergraduate degree, the path to success is clear; show up to lectures, learn what you’re told to learn and prepare well for your exams and you’ll do well. In a PhD, though, there isn’t such a clear path and in some PhD programmes there is no structure or guidance at all. Many students either give up or – worse – spend years – or sometimes decades – wrestling with an unfinished thesis.

If you’re lucky, you’ll find a great supervisor and other colleagues to guide you and support you. But if you’re unlucky, you’ll get a supervisor who ignores you and leaves you to figure everything out yourself. If you’re _very_ unlucky you can find yourself subject to outright exploitation, with supervisors keeping students around and actively holding them back because they want cheap labour.

Of course not all supervisors are exploitative, but few are given adequate training and most are under immense pressure, with teaching, administration, their own research and supervision all competing for their time and attention. Even when a supervisor has the best of intentions, it’s easy for PhD students to end up drifting alone, wondering what to do.

Doing a PhD to “complete” your education or for validation

Perhaps none of this puts you off and you want to do a PhD for the sake of “completing” your education or to find some kind of validation. This can be a powerful motivation, but it’s not necessarily a good one. If you think that doing a PhD is going to satisfy a sense of incompleteness, it won’t. Thinking this way pins far too much of your self-esteem on external validation and far too much pressure on the work.

If you’re doing a PhD to prove that you’re good enough, then when you face a problem, which is inevitable, it’s not just a practical issue but a threat to your sense of self-worth.

This can lead to a cycle of anxiety that’s difficult to escape, as the need for validation – or the fear of making a mistake or looking stupid – stops you taking risks or asking questions, which makes it harder to solve the problems that arise, which only adds to the sense of personal failure and increases the stress, which makes it harder to think and so on…

This is one of the reasons why some people never finish, because it’s easier to be a struggling student than to submit something and risk criticism.

But even if you get through to the end, getting the PhD certificate won’t necessarily solve that initial need for validation. You’ll get the congratulations, you’ll get the short-term high that comes from achieving a difficult goal, but then what? The high doesn’t last for long, and if you started with a need for validation, it’ll still be there when you finish.

A PhD is a means , not an end. If you can figure out what you’re trying to gain through a PhD, then you might see other, easier ways to achieve the same thing. For example, if you want to work on something important to you, it might be better to actually work in that field and have a more direct effect than to spend years reading and writing about it(fn). If you just want to continue your education because you’re interested in the subject, you can do so – without the constraints of specialisation or the demands of research – by reading. And if you’re thinking about a PhD because you need the validation, it’s probably better to try meditation and therapy to deal with the underlying issues more directly.

Too many students pursue a PhD, drawn by the perceived prestige, and end up suffering for no good reason. Unlike a job, which you can quit if you don’t like, there’s a sense that quitting a PhD is a personal failure(fn), even if the PhD isn’t giving you what you want in return. This creates a psychological trap where students are miserable but unable to finish but unable to walk away.

A PhD can be a wonderful experience.