- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Op-Ed Contributor

My Own Life

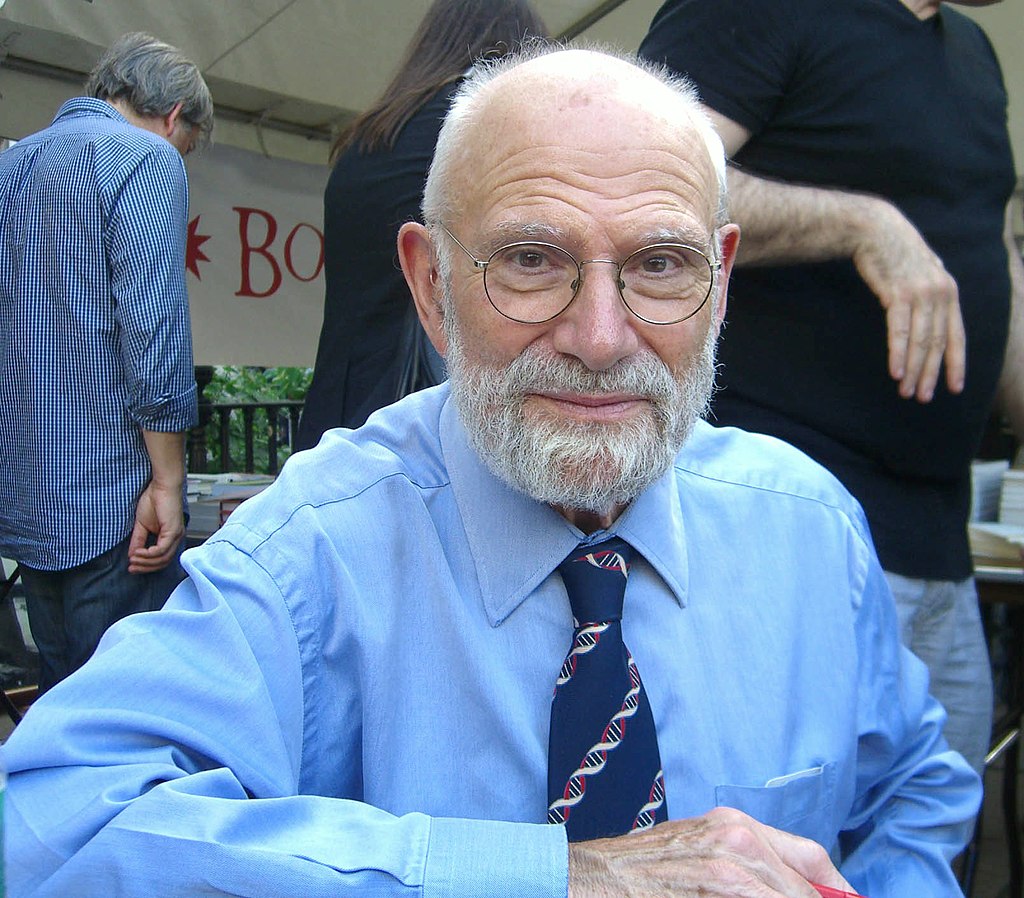

By Oliver Sacks

- Feb. 19, 2015

A MONTH ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out — a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver. Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma. The radiation and lasering to remove the tumor ultimately left me blind in that eye. But though ocular melanomas metastasize in perhaps 50 percent of cases, given the particulars of my own case, the likelihood was much smaller. I am among the unlucky ones.

I feel grateful that I have been granted nine years of good health and productivity since the original diagnosis, but now I am face to face with dying. The cancer occupies a third of my liver, and though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted.

It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me. I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can. In this I am encouraged by the words of one of my favorite philosophers, David Hume, who, upon learning that he was mortally ill at age 65, wrote a short autobiography in a single day in April of 1776. He titled it “My Own Life.”

“I now reckon upon a speedy dissolution,” he wrote. “I have suffered very little pain from my disorder; and what is more strange, have, notwithstanding the great decline of my person, never suffered a moment’s abatement of my spirits. I possess the same ardour as ever in study, and the same gaiety in company.”

I have been lucky enough to live past 80, and the 15 years allotted to me beyond Hume’s three score and five have been equally rich in work and love. In that time, I have published five books and completed an autobiography (rather longer than Hume’s few pages) to be published this spring; I have several other books nearly finished.

Hume continued, “I am ... a man of mild dispositions, of command of temper, of an open, social, and cheerful humour, capable of attachment, but little susceptible of enmity, and of great moderation in all my passions.”

Here I depart from Hume. While I have enjoyed loving relationships and friendships and have no real enmities, I cannot say (nor would anyone who knows me say) that I am a man of mild dispositions. On the contrary, I am a man of vehement disposition, with violent enthusiasms, and extreme immoderation in all my passions.

And yet, one line from Hume’s essay strikes me as especially true: “It is difficult,” he wrote, “to be more detached from life than I am at present.”

Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts. This does not mean I am finished with life.

On the contrary, I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.

This will involve audacity, clarity and plain speaking; trying to straighten my accounts with the world. But there will be time, too, for some fun (and even some silliness, as well).

I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective. There is no time for anything inessential. I must focus on myself, my work and my friends. I shall no longer look at “NewsHour” every night. I shall no longer pay any attention to politics or arguments about global warming.

This is not indifference but detachment — I still care deeply about the Middle East, about global warming, about growing inequality, but these are no longer my business; they belong to the future. I rejoice when I meet gifted young people — even the one who biopsied and diagnosed my metastases. I feel the future is in good hands.

I have been increasingly conscious, for the last 10 years or so, of deaths among my contemporaries. My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself. There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.

Because of an editing error, Oliver Sacks’s Op-Ed essay last Thursday misstated the proportion of cases in which the rare eye cancer he has — ocular melanoma — metastasizes. It is around 50 percent, not 2 percent, or “only in very rare cases.” When Dr. Sacks wrote, “I am among the unlucky 2 percent,” he was referring to the particulars of his case. (The likelihood of the cancer’s metastasizing is based on factors like the size and molecular features of the tumor, the patient’s age and the amount of time since the original diagnosis.)

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected] . Learn more

Oliver Sacks, a professor of neurology at the New York University School of Medicine, is the author of many books, including “Awakenings” and “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.”

Oliver Sacks passed away on Aug. 30, 2015.

The New York Times

Op-talk | readers respond: on ‘my own life’.

Readers Respond: On ‘My Own Life’

The neurologist whose writing opened a popular window on a medical “awakening” of the human mind shared his personal awakening after receiving a terminal cancer diagnosis. Readers responded to Oliver Sacks’ “ My Own Life ” with gratitude.

“I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts,” Mr. Sacks wrote. “I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.”

A science writer, a former medical student, the mother of a child with autism, a man on his “way out” and a man who, by chance, shared an airport lunch table with Mr. Sacks were among those who shared their own adventures of the mind. At least one skeptic weighed in.

As a young student engaged in the history of science, SAS from Newton, Mass. , wrote, “your books inspired, delighted and amazed me. When I had a child, I would read passages out loud to my daughter, who is now studying to become a neuroscientist. Your words have become part of the fabric of our lives.”

Mr. Sacks wrote of an intense sense of purpose in his remaining days, familiar in the literature of death and dying. “I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective,” he wrote. “There is no time for anything inessential.”

Daily marvels took on shape in comments, too.

“Each morning I observe the sun as it begins its glorious show. I observe flowers as they open, and our fish as they wander our pond,” Richard Schmidt wrote from Concord, N.C. “I observe our grandchildren, as they change each day. All is wonder.”

One reader said Mr. Sacks’s recitation of books written and manuscripts pending seemed out of place. The neurologist’s joys and intensity, rather than inspire him, brought to mind the shortcomings in his own life.

“It is depressing because it highlights my own lack of human connections and significant accomplishments,,” A. Davey wrote from Portland . “How can those of us who have suffered from isolation and disappointment take any comfort or guidance from these words?”

A former medical student of Mr. Sacks’s described the imposing bearded figure of the onetime weight lifter riding a motorcycle through New York City, and illustrated the humor of his gentle mentor.

“On demonstrating the gag response on me, to which I didn’t gag, he remarked: ‘Either you are missing the response or being very polite,’” Donald Green of Reading, Mass., wrote of one lesson. “He respectfully introduced us to patients who were later portrayed in ‘ Awakenings .’ It was eerie to have your memory jogged by a movie of something you had observed so closely years before.”

A reader with a terminal diagnosis of his own said reading Mr. Sacks’s work, he “learned about migraine; mysterious, Parkinsonian sleep; your British Jewish family; hallucination; music; and, above all, human idiosyncrasy,” G wrote from Virginia . “Your voice is clear and kind and, as I like to think, has inspired kindness in my own soul.”

A mother whose child has autism and “a brilliant, very alive mind” wrote to appreciate Mr. Sacks “for helping open minds to all of the wonderful human possibility expressed in the idea of neurodiversity.”

A New Yorker recounted a time at a California airport when an older man asked to sit at his table as they awaited their plane to the city. “As he sat quietly, eating his chicken noodle soup and crackers, I couldn’t help but notice that he looked familiar,” wrote Phillip from New York City , who realized eventually that he was sitting with the best-selling author. “Fortunately, I was prepared, having just finished reading ‘An Anthropologist on Mars’ and ‘Uncle Tungsten.’ … He even gave me a sneak preview of his forthcoming book on music.”

Mr. Sacks wrote that watching his generation fade out has pained him.

“Each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself,” he wrote. “It is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.”

Despite the pending abruption, some readers said Mr. Sacks’ life will continue to inspire imagination.

“I heard something at a friend’s funeral not too long ago about immortality — that we do live forever, and not just as memories,” Elizabeth Fuller wrote from Peterborough, N.H. “What we have done, said, and written lives on in ways big and small, often subconsciously, in those whose lives we have touched.”

What's Next

Reason and Meaning

Philosophical reflections on life, death, and the meaning of life, essays of the dying: neurologist oliver sacks.

Oliver Wolf Sacks, CBE (born 9 July 1933) is an American-British neurologist , writer, and amateur chemist who is Professor of Neurology at New York University School of Medicine . Between 2007 and 2012, he was professor of neurology and psychiatry at Columbia University , where he also held the position of “Columbia Artist”. Before that, he spent many years on the clinical faculty of Yeshiva University ‘s Albert Einstein College of Medicine . He also holds the position of visiting professor at the United Kingdom’s University of Warwick . [1]

Sacks is the author of numerous best-selling books, [2] including several collections of case studies of people with neurological disorders . His 1973 book Awakenings , an autobiographical account of his efforts to help victims of encephalitis lethargica regain proper neurological function, was adapted into the Academy Award -nominated film of the same name in 1990 starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro . He and his book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain were the subject of “ Musical Minds “, an episode of the PBS series Nova . [ from Wikipedia]

In a recent essay in the New York Times, “My Own Life,” Sachs announced that he has terminal cancer.

A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out — a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver … now I am face to face with dying. The cancer occupies a third of my liver, and though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted.

It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me. I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can. In this I am encouraged by the words of one of my favorite philosophers, David Hume, who, upon learning that he was mortally ill at age 65, wrote a short autobiography in a single day in April of 1776.

I have devoted a previous post to Hume’s courage in the face of death, and this line from Hume particularly resonates with Sachs: “It is difficult to be more detached from life than I am at present.” Here is the rest of the brief essay in full.

Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts. This does not mean I am finished with life.

On the contrary, I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.

This will involve audacity, clarity and plain speaking; trying to straighten my accounts with the world. But there will be time, too, for some fun (and even some silliness, as well).

I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective. There is no time for anything inessential. I must focus on myself, my work and my friends. I shall no longer look at “NewsHour” every night. I shall no longer pay any attention to politics or arguments about global warming.

This is not indifference but detachment — I still care deeply about the Middle East, about global warming, about growing inequality, but these are no longer my business; they belong to the future. I rejoice when I meet gifted young people — even the one who biopsied and diagnosed my metastases. I feel the future is in good hands.

I have been increasingly conscious, for the last 10 years or so, of deaths among my contemporaries. My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself. There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.

My Thoughts

When I think of all the athletes, soldiers, financiers, tycoons, actors, celebrities, and all the others who garner so much adulation from our culture, and compare them with the scientists who work in obscurity to shed a little light on our ignorance, I am ashamed that so many care more for the former than the latter.

I thank Professor Sachs for a lifetime of beneficial work in the service of humanity, and for his beautiful New York Times essay which exemplifies his intellectual and moral virtue. Goodbye Professor.

The nations wax, the nations wane away; In a brief space the generations pass, And like runners hand the lamp of life One unto another. ~ Lucretius

[Books by Oliver Sacks]

Share this:

Leave a reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The Oliver Sacks I Knew and Loved Once Saw Himself as a Failure

- October 19, 2024

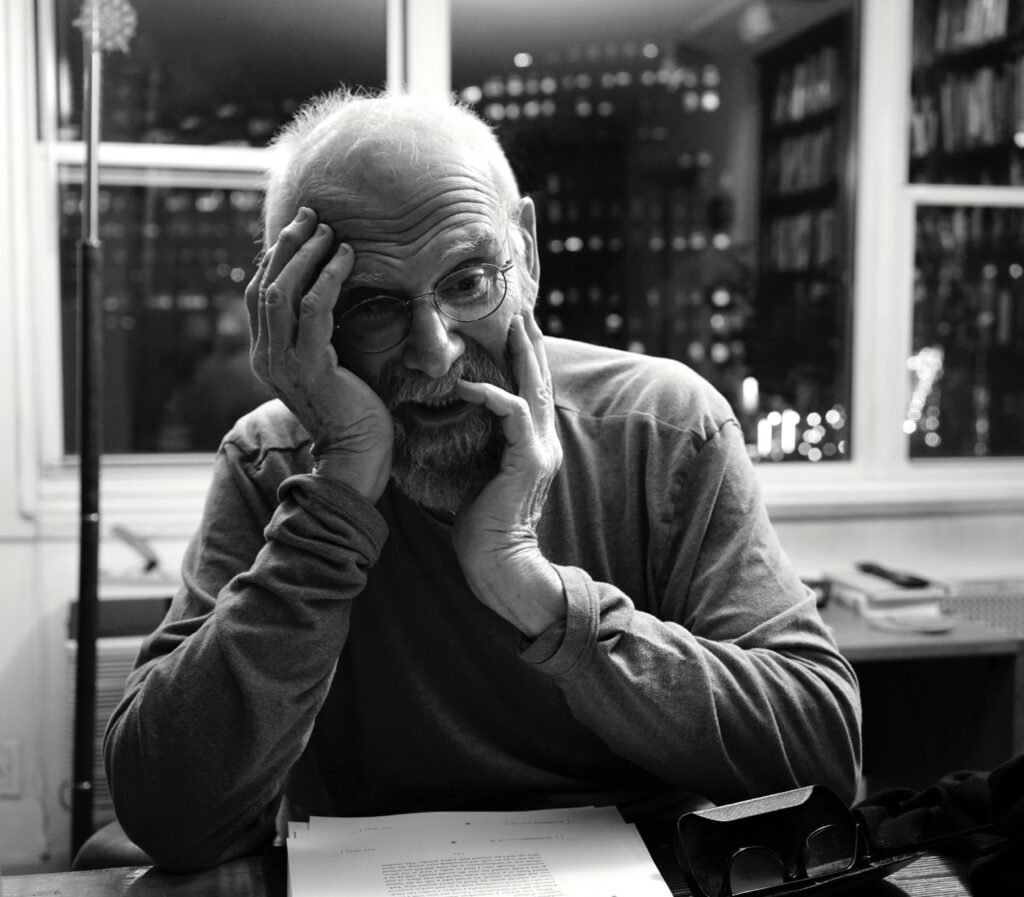

The Oliver Sacks that most of the world knew — the one I fell in love with after we met in 2008, when he was 75 — was the beloved neurologist and the author of many best-selling books, admired worldwide. A forthcoming volume of Oliver’s letters, nearly 350 of them, spanning 55 years, from age 27 to 82, provides a more complicated picture of the man often referred to in his later years as “the poet laureate of medicine.” Even I, his partner for the last six years of his life, was surprised by what I read in many of these letters, which will be published next month for the first time. (A selection of excerpts from the letters will appear below this essay.)

Episodes or stories I’d certainly heard about or read about in his autobiography “On the Move” come startlingly, vividly to life in the letters, illuminated as they are by the irrepressible now of Oliver’s voice. We are in his mind, in his thoughts, in the heat of the moment, as he bangs out letter after letter on a typewriter or with a fountain pen (Oliver never owned a computer or sent an email or text).

In 1965, a 31-year-old Oliver wrote a letter to his parents about his application for a position at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. The required letters of recommendation, he wrote, had been solicited and sent. Oliver, in an attempt at self-deprecating humor, included a mock quotation about him from an unnamed boss: “He arrives late, he rides a motorcycle, he dresses like a slob, but he has a good mind tucked away somewhere, and maybe you’ll have better luck with him than we have had. I like him, but he has given me a lot of gray hairs.”

He did land the job, and spent a number of years at Einstein and working at Beth Abraham Hospital, where he encountered the patients he would later write about in “Awakenings.” But he never quite found his way, made friends or fit in. In a desperate state during this period, he wrote a fevered letter to his favorite aunt, Len, wondering if, like his older brother Michael, he might be schizophrenic.

“Who am I? What sort of person am I? Under my glibness and my postures and my facades, my imitations, what is the real Oliver like? And, is there a real Oliver?” He added, “I have always felt transparent, without substance, a ghost, a transient, homeless, or outcast.”

It’s always tempting to draw a lesson from a famous person’s life. As Oliver’s partner, I have not so much a single lesson but an overwhelming sense of gratitude for our time together — the same sentiment he expressed in “My Own Life” and the other essays he wrote for The New York Times near the end of his life. But for others, the multitudes of readers who adored him and his work, there might be a message about what we think of as failure and the possibility of redemption.

The popular conception of Oliver’s career as both a neurologist and a writer was one of tremendous success from the start. But this was not the case. Oliver was 52 when his fourth book, “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” became a wholly unexpected best seller in 1986. In his 20s, 30s and 40s, his life and career had been not only unorthodox, but by many means, a disaster.

Both compulsive and impulsive, driven by self-destructive behavior (especially in his yearslong addiction to amphetamines, and what Oliver himself called periods of intense “mania”), he moved from job to job — twice getting fired — searching to find his way as a neurologist, as a writer and as a closeted gay man. While he had published three books before “Hat,” none had been markedly successful. Even his best-known book from that period, “Awakenings” (1973), didn’t sell well at the time — that wouldn’t change until the film adaptation in 1990 — and was largely ignored by his neurological colleagues.

His next book, “A Leg to Stand On” (1984), took him 11 torturous years and dozens of drafts to complete. In the meantime, other potential books were either lost, destroyed by Oliver in fits of frustration, or never finished. He despaired that he would ever amount to much, a sentiment echoed by those who knew him.Some of Oliver’s most revealing, passionate and numerous letters come during a short period in 1965, when he was 32, and that deal not with his mania or the frustrations of his medical career, but with love.

They were written in the aftermath of a fling he’d had during a week in Paris and Amsterdam with a Hungarian theater director named Jeno Vincze. The tone of these letters will be, for many people, a shock — they are that intense, both transcendentally beautiful and sometimes vicious. While Oliver had enjoyed countless hookups during his earlier time in San Francisco, living at the Y.M.C.A., no less, and had his heart broken by an unrequited romance with a young straight man in Los Angeles, this was the first time he had fallen so quickly and impulsively in love — a passion clearly fueled by drugs.

After returning to New York, he writes long letters to Jeno day after day: “My blood is champagne. I fizz with happiness,” he writes in the first letter, and in the next, “I love you insanely.” But soon Oliver grows impatient and suspicious, for Jeno’s replies do not come as quickly as he’d like: “I am a thermometer in your hand. Infamous week! Each day I waited for your letter. Each day I sank into deeper despair.”

This would be Oliver’s last romantic relationship of any significance for more than 40 years.

By the mid-1970s, he’d kicked drugs but was still adrift, fired from his job and picking up other gigs where he could. In a 1977 letter, he wrote to a former student about meeting some neurology colleagues at a conference: “When I mentioned my peripatetic, nomadic life … one of them said, ‘But, Oliver, this is all very — eccentric. You mean you don’t really have any position at your age?’ … ‘It is very simple,’ I answered, ‘I have the only real position there is … the only one with real tenure. My position is precisely at the center of medicine … at the very heart of medicine.’”

Oliver’s insistence on his own individuality, on being his most authentic self, mirrored his insistence on his patients’ individuality, on their absolute uniqueness as human beings, no matter how their neurological or psychiatric disorders made them feel. And ultimately, one might say, Oliver was his own most challenging and important patient.That one’s humanity is embedded in one’s genetic uniqueness is beautifully articulated in a 2006 reply to a young woman with bipolar disorder, who had asked him, “Am I just a mistake that somehow survived evolution’s ax?”

Though she was a stranger to him — one of his thousands of correspondents — Oliver replied by letter immediately: “What seems to me less stressed, and most in need of stressing,” he wrote to her, “is that you are an individual — unique — with gifts and genes which no one else in the world exactly duplicates — and that means you have a true place and role in evolution — and in the present. That you have bipolar disorder … does not begin to encompass the whole of you — it is a what, while you are a you. You have to hold to this sense of personhood … which is deeper than any ‘condition’ you have.”

By the time he wrote this letter, Oliver was 73 and, with the help of his longtime psychoanalyst as well as a small staff that helped keep him organized, had achieved a certain serenity that had eluded him for decades. Or perhaps “coherence” is a better, more accurate word. His life, with its multiple contradictions and warring impulses, the difficulties and rejections and often self-inflicted wounds, as well as his tremendous success, now finally all made sense.

This is who he was: equally a neurologist and a best-selling author; at the height of his considerable intellectual powers; and still as boyishly curious as an 8-year-old. Still practicing medicine and teaching, he was also writing prolifically with great joy and ease, one book or essay flowing seamlessly into the next. And perhaps most significantly, after a lifetime plagued by self-loathing and internalized homophobia — not to mention 35 years of celibacy — Oliver could acknowledge without shame that he was a gay man, ready to experience romance and a long-term domestic relationship for the first time.

Two years later, in 2008, we met. How? To my surprise, he wrote me a letter after reading my book “The Anatomist.” And I — living in San Francisco at the time — wrote Oliver a letter back. We had a brief correspondence, all very collegial. But, once I moved to New York a year later, he and I started spending time together and getting better and better acquainted, despite a 28-year age difference. By the summer of 2009, we were in love. We remained a couple until his death at 82 in August 2015. He continued to write and reply to letters until nearly the day he died.

For Oliver to become the man he did was a triumph of his passion and determination. This didn’t happen in a single moment, of course — it took faith in his own abilities, time and persistence. It took kicking drugs, years of psychoanalysis and acceptance from his literary and medical colleagues. But Oliver’s own story shows us, as his work so often did, that lonely, disordered and unorthodox lives are not hopeless. They can be improved, even healed. That’s a message he would have been delighted to give the world.

Bill Hayes is the author of “Insomniac City: New York, Oliver Sacks, and Me,” and “Sweat: A History of Exercise,” as well as the screenplay for a forthcoming film adaptation of “Insomniac City.”

The following excerpts from the forthcoming “Letters” of Oliver Sacks, edited by Kate Edgar, vividly depict the young Dr. Sacks struggling to find his way in the world as both a doctor and a writer, under the strain of intense self-doubt and battles with his own emotional and mental health.

MILK To Augustus S. Rose, chair of the U.C.L.A. department of neurology, Oct. 21, 1963, after receiving a letter from Dr. Rose reprimanding him for drinking milk from the hospital supplies.

I take strong exception to the moral aspersions implicit in your letter — if you regard me as a thief, I will make full restitution for the milk “stolen” (it must total at least $3), and take my leave at the end of the academic year.

I will no longer delude myself regarding the auspiciousness of my career at U.C.L.A., having spoiled my academic record by the heinous sins of untidiness, unpunctuality, and slaking my thirst at the ward refrigerator. But you must know, as well as I, that a man is not the sum of his minor misdemeanors, but of his best endeavors. You are well aware that I am not devoid of intelligence or of serious interest in the neurological sciences, and I shall still nourish the hope that you will not entirely abandon me if I seek your support in finding myself a position elsewhere next year.

PASSION To Jeno Vincze, a Hungarian theater director living in Berlin with whom Dr. Sacks had a brief, passionate affair, Oct. 4, 1965, Bronx.

My dearest Jeno:

I have clutched your letter in my pocket all day, and now I have time to write to you. It is 7 o’clock, the ending of a perfect day. The sun is mauve and crimson on the New York skyline. Reflected from the cubes and prisms of an Aztec city. Black clouds, like wolves, are racing through the sky. A jet is climbing on a long white tail. Howling wind. I love its howling, I want to howl for joy myself. The trees are thrashing to and fro. An old man runs after his hat. Darker now. The sun has set, City. A black diagram on the somber skyline. And soon there’ll be a billion lights. …

Your letter! What are you doing to me? I tore it open, and found myself trembling between tears and laughter. I pretended I had something in my eye, and rushed out of the room. You have said what I had intended to say. I wrote in my diary (my “diary” is really an endless letter to you, a conversation) after we’d been on the phone: I stride along the road too fast, driven by the rush of thoughts. My blood is champagne. I fizz with happiness. I smile like a lighthouse in all directions. Everyone catches and reflects my smile. They nod, and grin, and shout “great day.”

To Jeno Vincze, Oct. 6, 1965.

I love you insanely, yet it is the sweetest sanity I have ever known. I read and reread your wonderful letter. I feel it in my pocket through 10 layers of clothing. Its trust, its warmth, exceed anything I have ever known. …How constantly I talk with you! I write to you, continuously, in my diary. My last letter was overloaded, it had been building up for eight long days; it was congested, and in places false.

To Jeno Vincze, Oct. 12, 1965.

Still there? Still the same Jeno? Forgive me — it is eight days since I’ve heard from you. Eight days is nothing; one is busy; important business; the vagaries of the post; did I myself not keep you waiting for longer at a time of great uncertainty? True, true; completely true. I am too anxious, too demanding (like my mother who wants a letter every week: God forbid I should be as possessive as her!). But I feel like a fool writing to you — yet again — in the absence of response.

A LETHAL NEUROSIS To Dr. Sacks’ favorite aunt, Helena Landau, whom he affectionately called Auntie Len, Feb. 18, 1966, Bronx.

I had, to put it bluntly, no life whatever in New York. That is to say, no friends, no one I could go to, speak to, trust, enjoy; my “interests” became stale and empty to me: hospital a burden daily harder to bear; harder still to dissimulate my feelings of boredom and despair. I couldn’t eat, or sleep, saw no conceivable future, saw my whole past as worthless and hateful; I compounded a deteriorating situation by drug dependency, and — but why upset you with this horrible catalog? I found myself, in short, finding existence intolerable, seeing no point whatever in further existence. More than this, I found myself struggling with what was, in effect, an insistent, a peremptory inner demand for acts of self-destruction, culminating in self-murder. I was in the grip of what one might term a lethal neurosis. … What has happened to me en route so that I am slipping down the greased path of withdrawal, discontent, inability to make friends, inability to have sex, etc., etc., towards suicide in a New York apartment at the age of 32?

REGRETS To Melvin Erpelding, a friend, December 1966, New York City.

How we have traveled, Mel! Always fleeing, always seeking, always deceiving ourselves, never arriving. Anchored to the Past, dreaming of the Future, and — in some fatal, blind sense — oblivious to the Present.

Lists of regrets, manufacture of dreams! I say to myself: Why did I leave Santa Monica? Beaches, white foam, Topanga, friends, the exhilaration which saturated every day. Bah! But what madness to leave San Francisco! Aerial, hilly, New Jerusalem. Or why did I not stay in the wilds, in the backwoods of Canada, a lumberman and poet? Or was not the real spitefulness ever to leave London — my only, wondrous London — my home, and the home of my people? Or was the real and ultimate sadness to grow up, to leave the Magic Region of childhood, the time of wish-fulfilment and infinite power, the feeling of love and an endless future?

Idiocy! It is all idiocy and vain regrets. Fatally easy to transfigure the past, to see in it millennia of epic happiness followed by cruel unmerited expulsions. It is the myth of Genesis all over again.

‘I HAVE UTTERLY BLOWN MY EGO TO PIECES’ To his friend Jonathan Miller, Sept. 23, 1968, New York City.

It has been an incredible three weeks, a concentrated, maniacal, annus mirabile. I have had a superb eruption of creative powers — I will never know more, generically, than I know now — and in so doing, as perhaps I always feared (and good reason to refrain from the danger!) I have utterly blown my ego to pieces. I suppose it might be called an acute schizophrenic psychosis, if labels are useful. Certainly I have been fantastically, beautifully hallucinated in the past week; the entire world has been no more than a tabula rasa on which I would project my metaphors as hallucinations …

A MAN WITHOUT A HOME To Jonathan Cole, a medical student seeking to work with Dr. Sacks, March 21, 1976, Mount Vernon, N.Y. (Dr. Cole did come to work with Dr. Sacks the next year, and they became lifelong friends.)

I very much appreciate your generous response to my books, and feel grateful (and amazed!) that you should want to work with me.

My delay in replying is because I don’t know what to reply. But here, roughly, is my “situation”:

a) I don’t have a department.

b) I am not in a department.

c) I am a “gypsy,” and survive — rather marginally and precariously — on “odd jobs” here and there.

When I worked full-time at Beth Abraham (the “Mount Carmel” of “Awakenings”), I often had students spend some weeks with me for their “electives” — and this was an experience we would always find very pleasant and rewarding. I have the happiest memories of those far-off days.

But now I am, as it were, without any “position” or “base” or “home,” but peripatetic here and there, I can’t possibly offer any formal sort of teaching — or anything which could be formally “accredited” to you. … I have all the disadvantages, as I have all the advantages, of being a Non-Establishment, Non-Established, person — I rove freely and widely; I spend as long as I want with any patient I want; but I have no department, no courses, no colleagues, no help, no “position” (and for good measure no “security,” and almost no “means”).

HOPE To Wendy, a college student who had written to Dr. Sacks about her bipolar disorder, Nov. 14, 2006.

What seems to me less stressed, and most in need of stressing, is that you are an individual — unique — with gifts and genes which no one else in the world exactly duplicates — and that means you have a true place and role in evolution, and in the present. That you have bipolar disorder, in a sense are bipolar, does not begin to encompass the whole of you — it is a what, while you are a you. You have to hold to this sense of a personhood (“personality” is not quite the word, it has got too Hollywoodized) — Coleridge talked about “personeity,” which is deeper than any “condition” you have, and perhaps these (relatively) gentle years at Gould Farm will allow you to realize this (realize it, in both senses — understand and actualize). You have much to hope and to live for. So, my best to you and keep in touch.

Published in The New York Times on October 19, 2021

Recent Essays

Sometimes You Have to Hate Exercise Before You Can Love It Again

12 Encounters with New York City

On Editing Oliver Sacks

Swimming In Words With Oliver Sacks

New Essay in NYT Magazine on 1981-1983

Essay Archives

“One of those rare authors who can tackle just about any subject in book form, and make you glad he did.” — San Francisco Chronicle

- Login / Sign Up

Believe that journalism can make a difference

If you believe in the work we do at Vox, please support us this Giving Tuesday. Our mission has never been more urgent. But our work isn’t easy. It requires resources, dedication, and independence. And that’s where you come in.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

Oliver Sacks has written a beautiful, heart-breaking essay on his terminal cancer diagnosis

by Julia Belluz

Up until a month ago, popular author and neurologist Oliver Sacks was in great health, even swimming a mile every day. Then, everything changed: the 81-year-old was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer.

In a beautiful op-ed , published today in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he’ll face his final moments:

Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts. This does not mean I am finished with life. On the contrary, I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight. This will involve audacity, clarity and plain speaking; trying to straighten my accounts with the world. But there will be time, too, for some fun (and even some silliness, as well).

The entire essay is worth your time. Read it here .

Read more from Vox:

- How Americans’ refusal to talk about death hurts the elderly

Most Popular

- How weed won over America

- The Supreme Court seems likely to reverse a ridiculous decision about vaping

- Are progressive groups sinking Democrats' electoral chances?

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- Who killed JonBenét Ramsey? Everything we know about the main suspects.

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

We need new malaria drugs — so I spent a year as a guinea pig.

Xenotransplantation raises major moral questions — and not just about the pigs.

Neuroscience is revealing a fascinating link between gratitude and generosity.

Whatever you do, don’t call the Black in Neuro founder “resilient.”

Science should be bipartisan. Why is our confidence split down party lines?

Who owns the escaped monkeys now? It’s more complicated than you might think.

Third Act Project

Don't Die Til You're Dead

My Own Life

In this poignant and compelling essay, Oliver Sacks describes his reactions to learning about his diagnosis of terminal liver cancer. In the context of an all too deadly future his words evoke a powerful, inspiring, albeit tear filled sense of “Yesss!!” And “Go for it!”

There’s a sense here that reminds me of Daniel Klein’s phrase, “waiting for the diagnosis.” And then what do we do? Terrifying, and yet many Third Actors have to deal with it. How do you carry on your life with the sword of Damocles hovering overhead? How do you “ go for it after knowing your time is short? It is in such moments, that we hope to be able to evoke the Project’s mantra: Don’t die till you’re dead!

Tell us how you may have come to terms with this all consuming situation. So many will be grateful for your story.

A MONTH ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out — a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver. Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma. The radiation and lasering to remove the tumor ultimately left me blind in that eye. But though ocular melanomas metastasize in perhaps 50 percent of cases, given the particulars of my own case, the likelihood was much smaller. I am among the unlucky ones.

I feel grateful that I have been granted nine years of good health and productivity since the original diagnosis, but now I am face to face with dying. The cancer occupies a third of my liver, and though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted.

It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me. I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can. In this I am encouraged by the words of one of my favorite philosophers, David Hume, who, upon learning that he was mortally ill at age 65, wrote a short autobiography in a single day in April of 1776. He titled it My Own Life .

“I now reckon upon a speedy dissolution,” he wrote. “I have suffered very little pain from my disorder; and what is more strange, have, notwithstanding the great decline of my person, never suffered a moment’s abatement of my spirits. I possess the same ardour as ever in study, and the same gaiety in company.”

I have been lucky enough to live past 80, and the 15 years allotted to me beyond Hume’s three score and five have been equally rich in work and love. In that time, I have published five books and completed an autobiography (rather longer than Hume’s few pages) to be published this spring; I have several other books nearly finished.

Hume continued, “I am … a man of mild dispositions, of command of temper, of an open, social, and cheerful humour, capable of attachment, but little susceptible of enmity, and of great moderation in all my passions.”

Here I depart from Hume. While I have enjoyed loving relationships and friendships and have no real enmities, I cannot say (nor would anyone who knows me say) that I am a man of mild dispositions. On the contrary, I am a man of vehement disposition, with violent enthusiasms, and extreme immoderation in all my passions.

And yet, one line from Hume’s essay strikes me as especially true: “It is difficult,” he wrote, “to be more detached from life than I am at present.”

Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts. This does not mean I am finished with life.

On the contrary, I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.

This will involve audacity, clarity and plain speaking; trying to straighten my accounts with the world. But there will be time, too, for some fun (and even some silliness, as well).

I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective. There is no time for anything inessential. I must focus on myself, my work and my friends. I shall no longer look at “NewsHour” every night. I shall no longer pay any attention to politics or arguments about global warming.

This is not indifference but detachment — I still care deeply about the Middle East, about global warming, about growing inequality, but these are no longer my business; they belong to the future. I rejoice when I meet gifted young people — even the one who biopsied and diagnosed my metastases. I feel the future is in good hands.

I have been increasingly conscious, for the last 10 years or so, of deaths among my contemporaries. My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself. There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times on Feb. 19, 2015. Oliver Sacks passed away on Aug. 30, 2015.

One thought on “ My Own Life ”

Plato once remarked that he lived with “one foot in the grave”. Is there anything more important than constantly nurturing our awareness of our fragility & impermanence as well as a sense of intense gratitude? What a gift Oliver Sacks possessed and has shared with us throughout his extraordinary career.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

COMMENTS

In this I am encouraged by the words of one of my favorite philosophers, David Hume, who, upon learning that he was mortally ill at age 65, wrote a short autobiography in a single day in April...

In this I am encouraged by the words of one of my favorite philosophers, David Hume, who, upon learning that he was mortally ill at age 65, wrote a short autobiography in a single day in April of 1776. He titled it “My Own Life.” “I now reckon upon a speedy dissolution,” he wrote.

Readers responded to Oliver Sacks’ “ My Own Life” with gratitude. “I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the...

In a recent essay in the New York Times, “My Own Life,” Sachs announced that he has terminal cancer. A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out — a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver … now I am face to face with dying.

In his essay, Sacks shows a profound anticipation of his own impending death, but with a wonderful sense of gratitude for all he has experienced in his life: ‘Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure’.

My Own Life. Oliver Sacks - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Oliver Sacks, a renowned neurologist and author, has learned that the rare eye cancer he was diagnosed with 9 years ago has now metastasized and spread to his liver.

The following excerpts from the forthcoming “Letters” of Oliver Sacks, edited by Kate Edgar, vividly depict the young Dr. Sacks struggling to find his way in the world as both a doctor and a writer, under the strain of intense self-doubt and battles with his own emotional and mental health.

In a beautiful op-ed, published today in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he’ll face his final moments: Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from...

In this poignant and compelling essay, Oliver Sacks describes his reactions to learning about his diagnosis of terminal liver cancer. In the context of an all too deadly future his words evoke a powerful, inspiring, albeit tear filled sense of “Yesss!!”

Oliver Sacks learns he has terminal liver cancer that has metastasized from a rare eye cancer diagnosed 9 years prior. Though initially healthy, he now faces mortality. Taking inspiration from David Hume's writing upon learning of his own mortality, Sacks reflects on making the most of the remaining months of his life through deepening ...