How to Title a Research Proposal

Coming up with a good title for your research proposal can be tricky. It’s often the first thing people see, so it needs to grab their attention and give them a clear idea of what your research is about.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through the process of creating an effective title for your research proposal. We’ll cover why titles matter, what makes a good title, and give you step-by-step instructions on how to craft one. By the end, you’ll have all the tools you need to create a title that makes your proposal shine.

Why Your Research Proposal Title Matters

Before we dive into the how-to, let’s talk about why your title is so important:

- First Impressions Count

Think of your title as the cover of a book. It’s the first thing people see, and it can make them either want to read more or move on to something else. A good title can make people curious and excited about your research.

- It Sets the Tone

Your title gives readers a sneak peek into what your research is all about. It can hint at your approach, your findings, or the importance of your work.

- It Helps People Find Your Work

In the world of academic research, a good title can help your work show up in searches. This means more people might read and use your research.

- It Shows You Know Your Stuff

A clear, well-thought-out title shows that you understand your research topic and can explain it well. This can make people more likely to trust your work.

What Makes a Good Research Proposal Title?

Now that we know why titles are important, let’s look at what makes a title good:

- Clear and Specific

A good title tells readers exactly what your research is about. It shouldn’t be vague or confusing.

Example: Vague: “A Study of Plants” Clear and Specific: “The Effects of Increased Carbon Dioxide Levels on Tomato Plant Growth”

While your title should be clear, it also needs to be short. Aim for about 10-15 words. If you need more, consider using a subtitle.

Your title should make people want to read more. This doesn’t mean it needs to be flashy, but it should be interesting.

- Informative

A good title gives readers key information about your research. This might include the main topic, the population you’re studying, or your method.

- Uses Keywords

Include important words related to your research. This helps people find your work when they’re searching for information on your topic.

- Avoids Jargon and Abbreviations

Unless you’re writing for a very specific audience, try to use words that most people can understand. Avoid abbreviations unless they’re very well-known in your field.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Research Proposal Title

Now, let’s walk through the process of creating your title:

Step 1: Identify Your Main Topic

Start by pinpointing the main focus of your research. What’s the big question you’re trying to answer?

Example: If you’re studying how social media affects teenagers’ mental health, your main topic might be “social media and teen mental health.”

Step 2: Specify Your Approach or Method

Next, think about how you’re going to study this topic. Are you doing experiments? Surveys? Analyzing existing data?

Example: If you’re using surveys to study social media and teen mental health, you might add “A Survey-Based Study” to your title.

Step 3: Highlight Your Unique Angle

What makes your research different or interesting? Is there a specific aspect you’re focusing on?

Example: Maybe you’re specifically looking at how different types of social media platforms affect teen mental health. You could add this to your title.

Step 4: Consider Your Target Audience

Think about who will be reading your proposal. Are they experts in your field, or could they be from a variety of backgrounds? This will help you decide how technical your title should be.

Step 5: Draft Your Title

Now, put all these elements together into a draft title.

Example: “The Impact of Different Social Media Platforms on Teenage Mental Health: A Survey-Based Study”

Step 6: Refine and Polish

Look at your draft title and ask yourself:

- Is it clear?

- Is it specific enough?

- Is it too long?

- Does it use important keywords?

- Would it make someone want to read more?

Make adjustments based on your answers.

Step 7: Get Feedback

Show your title to others – your peers, your advisor, or even someone outside your field. Ask them what they think the research is about based on the title. Their feedback can help you make your title even better.

Step 8: Final Check

Before you finalize your title, do one last check:

- Proofread for any spelling or grammar errors

- Make sure it follows any specific guidelines for your proposal submission

- Confirm that it accurately represents your research

Types of Research Proposal Titles

There are several common types of titles you might use for your research proposal. Let’s look at each type and when you might use it:

- Descriptive Titles

These titles simply describe what the research is about. They’re straightforward and clear.

When to use: When you want to be direct and your research doesn’t need a catchy hook.

Example: “The Effects of Exercise on Depression in Older Adults”

- Interrogative Titles

These titles pose a question that the research aims to answer.

When to use: When your research is exploratory or when you want to highlight the main question you’re addressing.

Example: “Can Regular Exercise Reduce Symptoms of Depression in Older Adults?”

- Declarative Titles

These titles make a statement about the findings or conclusions of the research.

When to use: When you have strong findings or a clear argument to make. Be careful with these for proposals, as they might seem presumptuous if you haven’t done the research yet.

Example: “Regular Exercise Significantly Reduces Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults”

- Two-Part Titles

These titles have two parts, usually separated by a colon. The first part is often catchy or general, while the second part is more specific.

When to use: When you want to grab attention but also need to be specific about your research.

Example: “Moving Towards Happiness: The Impact of Exercise on Depression in Older Adults”

- Metaphorical Titles

These titles use figurative language to describe the research in an engaging way.

When to use: When you want to be creative and your field allows for less formal titles. Be careful not to sacrifice clarity for creativity.

Example: “Sweating Away the Blues: How Exercise Combats Depression in the Elderly”

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Research Proposal Titles

Now that we’ve covered how to create a good title, let’s look at some common mistakes to avoid:

- Being Too Vague

A title that’s too general doesn’t give readers enough information about your specific research.

Bad example: “A Study of Mental Health” Better: “The Impact of Social Support on Mental Health Outcomes in First-Year College Students”

- Using Jargon or Obscure Abbreviations

Remember, not everyone who reads your title will be an expert in your field.

Bad example: “The Effect of HIIT on VO2 Max in Sedentary Adults” Better: “The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Fitness in Inactive Adults”

- Making it Too Long

While you want to be informative, a title that’s too long can be hard to read and remember.

Bad example: “An Investigation into the Effects of Different Types of Social Media Usage on the Mental Health and Well-being of Teenagers Aged 13-18 in Urban Areas” Better: “Social Media Use and Mental Health in Urban Teenagers: A Comparative Study”

- Being Misleading

Your title should accurately reflect your research. Don’t promise something your study doesn’t deliver.

Bad example: “Curing Depression Through Exercise” (if your study only shows exercise may help reduce symptoms) Better: “The Role of Exercise in Managing Depressive Symptoms”

- Using Sensational Language

While you want your title to be interesting, avoid using exaggerated or sensational language.

Bad example: “Shocking Discoveries About Diet and Cancer” Better: “New Insights into the Relationship Between Diet and Cancer Risk”

- Forgetting Keywords

Including relevant keywords helps people find your research.

Bad example: “A Look at Online Behavior” Better: “Cyberbullying Patterns in Adolescent Social Media Use”

- Using Questions That Can Be Answered With “Yes” or “No”

If you use a question in your title, make sure it’s not too simplistic.

Bad example: “Does Diet Affect Health?” Better: “How Do Different Dietary Patterns Impact Long-term Health Outcomes?”

Examples of Good Research Proposal Titles

To help you get a better idea of what good titles look like, here are some examples from different fields:

Psychology: “The Role of Mindfulness Meditation in Reducing Workplace Stress: A Randomized Controlled Trial”

Environmental Science: “Urban Green Spaces and Air Quality: Measuring the Impact of City Parks on Local Pollution Levels”

Education: “Gamification in the Classroom: Evaluating the Effects on Student Engagement and Learning Outcomes”

Sociology: “Breaking the Cycle: Intergenerational Poverty and the Impact of Early Childhood Education Programs”

Medical Research: “Exploring the Gut-Brain Axis: The Relationship Between Microbiome Composition and Anxiety Disorders”

Technology: “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Developing Predictive Models for Early Disease Detection”

History: “Voices from the Past: Oral Histories of World War II Veterans and Their Impact on Historical Narratives”

Business: “The Gig Economy and Worker Satisfaction: A Comparative Study of Full-time and Freelance Professionals”

Literature: “Beyond the Canon: Diversifying English Literature Curricula and Its Effects on Student Engagement”

Physics: “Quantum Entanglement in Macroscopic Systems: New Approaches for Scalable Quantum Computing”

These examples show how a good title can convey the main topic, the approach or method, and sometimes even hint at the potential findings or importance of the research.

Tailoring Your Title to Different Audiences

It’s important to remember that you might need to adjust your title depending on who will be reading it. Here are some tips for tailoring your title to different audiences:

- Academic Audience

When writing for other researchers or academics in your field:

- You can use some specialized terminology, but still avoid obscure jargon

- Be precise about your research methods and focus

- Include relevant theoretical frameworks if applicable

Example: “Applying Self-Determination Theory to Online Learning: A Mixed-Methods Study of Student Motivation and Achievement”

- Grant Committees

When applying for funding:

- Emphasize the potential impact or relevance of your research

- Use language that non-experts can understand

- Highlight the innovative aspects of your study

Example: “Tackling Antibiotic Resistance: Developing Novel Treatments for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections”

- General Public

If your research might be read by a general audience:

- Avoid all jargon and technical terms

- Focus on the real-world applications or implications of your work

- Use engaging, accessible language

Example: “Can What We Eat Affect How We Feel? Exploring the Link Between Diet and Depression”

- Interdisciplinary Audience

If your research crosses multiple fields:

- Use language that’s accessible to people from different backgrounds

- Clearly show how your research connects different areas

- Avoid field-specific jargon

Example: “Merging Art and Science: Using Virtual Reality to Enhance Museum Experiences and Learning Outcomes”

- Policy Makers

If your research has policy implications:

- Highlight the practical applications or policy relevance of your work

- Use clear, straightforward language

- Focus on the potential impact on society or specific populations

Example: “Bridging the Digital Divide: Evaluating Strategies to Increase Internet Access in Rural Communities”

Remember, no matter who your audience is, your title should always be clear, informative, and engaging.

Revising and Refining Your Title

Creating a great title often involves several rounds of revision. Here are some strategies to help you refine your title:

- Sleep on It

After you’ve drafted your title, leave it for a day or two. When you come back to it, you might see ways to improve it that weren’t obvious before.

- Read it Out Loud

Sometimes, hearing your title can help you identify awkward phrasing or words that don’t quite fit.

- Try Different Versions

Come up with several different titles for your proposal . You might find that combining elements from different versions leads to the best result.

- Use the “So What?” Test

Ask yourself, “So what?” about your title. Does it convey why your research matters? If not, consider how you can tweak it to show the significance of your work.

- Check for Clarity

Ask someone unfamiliar with your research to read your title. Can they tell you what your research is about? If not, you might need to make your title clearer.

- Consider SEO

If your research will be published online, think about search engine optimization (SEO). Include important keywords that people might use when searching for research like yours.

- Compare with Other Titles

Look at titles of similar research in your field. How does yours compare? This can give you ideas for improvement.

- Cut Unnecessary Words

Go through your title word by word. Is each one necessary? Can you say the same thing with fewer words?

- Check Guidelines

Make sure your title follows any guidelines provided by your institution, funding body, or the place where you’re submitting your proposal.

- Get Professional Feedback

If possible, ask your advisor or a colleague in your field to review your title. They might offer valuable insights or suggestions.

How to Write a Comprehensive PhD Research Proposal in Sociology

How to Write a Research Proposal for Business Psychology

How To Write An Effective Research Proposal Title

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

To wrap up, let’s address some frequently asked questions about research proposal titles:

Q1: How long should my research proposal title be? A: Aim for about 10-15 words. If you need more, consider using a subtitle.

Q2: Should I use questions in my title? A: Questions can be effective, especially for exploratory research. Just make sure they’re not too simple or easily answered with a yes or no.

Q3: Is it okay to use humor in my title? A: It depends on your field and audience. In most academic settings, it’s better to err on the side of being professional rather than humorous.

Q4: Should I include my research methods in the title? A: If your method is a key part of what makes your research unique or important, then yes. Otherwise, it’s not always necessary.

Q5: Can I use abbreviations in my title? A: It’s generally best to avoid abbreviations unless they’re very well-known in your field.

Q6: How do I know if my title is too technical? A: Ask someone outside your field to read it. If they can’t understand what your research is about, you might need to simplify your language.

Q7: Is it okay to use a colon in my title? A: Yes, using a colon to separate a general topic from a more specific description is a common and effective title format.

Q8: Should my title describe my results? A: For a research proposal, usually not, since you haven’t done the research yet. Your title should describe what you plan to study.

Q9: How important is the order of words in my title? A: Very important. Put the most crucial information at the beginning of your title where it’s most likely to grab attention.

Q10: Can I change my title after I’ve submitted my proposal? A: This depends on the rules of where you’re submitting. In many cases, you can refine your title as your research progresses, but check with your advisor or the submission guidelines.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Post navigation

Previous post.

📕 Studying HQ

Typically replies within minutes

Hey! 👋 Need help with an assignment?

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

WhatsApp us

17 Research Proposal Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

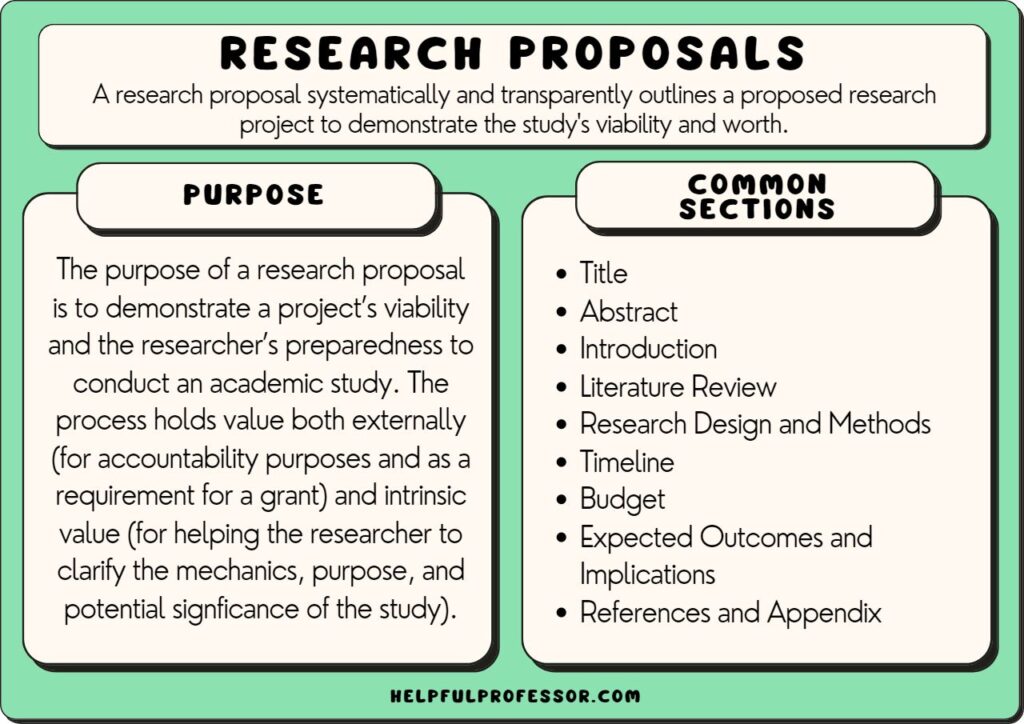

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.

Introduction: Introductions are all about contextualization. They often set the background information with a statement of the problem. At the end of the introduction, the reader should understand what the rationale for the study truly is. I like to see the research questions or hypotheses included in the introduction and I like to get a good understanding of what the significance of the research will be. It’s often easiest to write the introduction last

Literature Review: The literature review dives deep into the existing literature on the topic, demosntrating your thorough understanding of the existing literature including themes, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the literature. It serves both to demonstrate your knowledge of the field and, to demonstrate how the proposed study will fit alongside the literature on the topic. A good literature review concludes by clearly demonstrating how your research will contribute something new and innovative to the conversation in the literature.

Research Design and Methods: This section needs to clearly demonstrate how the data will be gathered and analyzed in a systematic and academically sound manner. Here, you need to demonstrate that the conclusions of your research will be both valid and reliable. Common points discussed in the research design and methods section include highlighting the research paradigm, methodologies, intended population or sample to be studied, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures . Toward the end of this section, you are encouraged to also address ethical considerations and limitations of the research process , but also to explain why you chose your research design and how you are mitigating the identified risks and limitations.

Timeline: Provide an outline of the anticipated timeline for the study. Break it down into its various stages (including data collection, data analysis, and report writing). The goal of this section is firstly to establish a reasonable breakdown of steps for you to follow and secondly to demonstrate to the assessors that your project is practicable and feasible.

Budget: Estimate the costs associated with the research project and include evidence for your estimations. Typical costs include staffing costs, equipment, travel, and data collection tools. When applying for a scholarship, the budget should demonstrate that you are being responsible with your expensive and that your funding application is reasonable.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: A discussion of the anticipated findings or results of the research, as well as the potential contributions to the existing knowledge, theory, or practice in the field. This section should also address the potential impact of the research on relevant stakeholders and any broader implications for policy or practice.

References: A complete list of all the sources cited in the research proposal, formatted according to the required citation style. This demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the relevant literature and ensures proper attribution of ideas and information.

Appendices (if applicable): Any additional materials, such as questionnaires, interview guides, or consent forms, that provide further information or support for the research proposal. These materials should be included as appendices at the end of the document.

Research Proposal Examples

Research proposals often extend anywhere between 2,000 and 15,000 words in length. The following snippets are samples designed to briefly demonstrate what might be discussed in each section.

1. Education Studies Research Proposals

See some real sample pieces:

- Assessment of the perceptions of teachers towards a new grading system

- Does ICT use in secondary classrooms help or hinder student learning?

- Digital technologies in focus project

- Urban Middle School Teachers’ Experiences of the Implementation of

- Restorative Justice Practices

- Experiences of students of color in service learning

Consider this hypothetical education research proposal:

The Impact of Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Middle School Mathematics

Abstract: The proposed study will explore multiplayer game-based learning techniques in middle school mathematics curricula and their effects on student engagement. The study aims to contribute to the current literature on game-based learning by examining the effects of multiplayer gaming in learning.

Introduction: Digital game-based learning has long been shunned within mathematics education for fears that it may distract students or lower the academic integrity of the classrooms. However, there is emerging evidence that digital games in math have emerging benefits not only for engagement but also academic skill development. Contributing to this discourse, this study seeks to explore the potential benefits of multiplayer digital game-based learning by examining its impact on middle school students’ engagement and academic performance in a mathematics class.

Literature Review: The literature review has identified gaps in the current knowledge, namely, while game-based learning has been extensively explored, the role of multiplayer games in supporting learning has not been studied.

Research Design and Methods: This study will employ a mixed-methods research design based upon action research in the classroom. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test control group design will first be used to compare the academic performance and engagement of middle school students exposed to game-based learning techniques with those in a control group receiving instruction without the aid of technology. Students will also be observed and interviewed in regard to the effect of communication and collaboration during gameplay on their learning.

Timeline: The study will take place across the second term of the school year with a pre-test taking place on the first day of the term and the post-test taking place on Wednesday in Week 10.

Budget: The key budgetary requirements will be the technologies required, including the subscription cost for the identified games and computers.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: It is expected that the findings will contribute to the current literature on game-based learning and inform educational practices, providing educators and policymakers with insights into how to better support student achievement in mathematics.

2. Psychology Research Proposals

See some real examples:

- A situational analysis of shared leadership in a self-managing team

- The effect of musical preference on running performance

- Relationship between self-esteem and disordered eating amongst adolescent females

Consider this hypothetical psychology research proposal:

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress Reduction in College Students

Abstract: This research proposal examines the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on stress reduction among college students, using a pre-test/post-test experimental design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods .

Introduction: College students face heightened stress levels during exam weeks. This can affect both mental health and test performance. This study explores the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation as a way to mediate stress levels in the weeks leading up to exam time.

Literature Review: Existing research on mindfulness-based meditation has shown the ability for mindfulness to increase metacognition, decrease anxiety levels, and decrease stress. Existing literature has looked at workplace, high school and general college-level applications. This study will contribute to the corpus of literature by exploring the effects of mindfulness directly in the context of exam weeks.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n= 234 ) will be randomly assigned to either an experimental group, receiving 5 days per week of 10-minute mindfulness-based interventions, or a control group, receiving no intervention. Data will be collected through self-report questionnaires, measuring stress levels, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ experiences, and students’ test scores.

Timeline: The study will begin three weeks before the students’ exam week and conclude after each student’s final exam. Data collection will occur at the beginning (pre-test of self-reported stress levels) and end (post-test) of the three weeks.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: The study aims to provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing stress among college students in the lead up to exams, with potential implications for mental health support and stress management programs on college campuses.

3. Sociology Research Proposals

- Understanding emerging social movements: A case study of ‘Jersey in Transition’

- The interaction of health, education and employment in Western China

- Can we preserve lower-income affordable neighbourhoods in the face of rising costs?

Consider this hypothetical sociology research proposal:

The Impact of Social Media Usage on Interpersonal Relationships among Young Adults

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effects of social media usage on interpersonal relationships among young adults, using a longitudinal mixed-methods approach with ongoing semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data.

Introduction: Social media platforms have become a key medium for the development of interpersonal relationships, particularly for young adults. This study examines the potential positive and negative effects of social media usage on young adults’ relationships and development over time.

Literature Review: A preliminary review of relevant literature has demonstrated that social media usage is central to development of a personal identity and relationships with others with similar subcultural interests. However, it has also been accompanied by data on mental health deline and deteriorating off-screen relationships. The literature is to-date lacking important longitudinal data on these topics.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n = 454 ) will be young adults aged 18-24. Ongoing self-report surveys will assess participants’ social media usage, relationship satisfaction, and communication patterns. A subset of participants will be selected for longitudinal in-depth interviews starting at age 18 and continuing for 5 years.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of five years, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between social media usage and interpersonal relationships among young adults, potentially informing social policies and mental health support related to social media use.

4. Nursing Research Proposals

- Does Orthopaedic Pre-assessment clinic prepare the patient for admission to hospital?

- Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of providing psychological care to burns patients

- Registered psychiatric nurse’s practice with mentally ill parents and their children

Consider this hypothetical nursing research proposal:

The Influence of Nurse-Patient Communication on Patient Satisfaction and Health Outcomes following Emergency Cesarians

Abstract: This research will examines the impact of effective nurse-patient communication on patient satisfaction and health outcomes for women following c-sections, utilizing a mixed-methods approach with patient surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Introduction: It has long been known that effective communication between nurses and patients is crucial for quality care. However, additional complications arise following emergency c-sections due to the interaction between new mother’s changing roles and recovery from surgery.

Literature Review: A review of the literature demonstrates the importance of nurse-patient communication, its impact on patient satisfaction, and potential links to health outcomes. However, communication between nurses and new mothers is less examined, and the specific experiences of those who have given birth via emergency c-section are to date unexamined.

Research Design and Methods: Participants will be patients in a hospital setting who have recently had an emergency c-section. A self-report survey will assess their satisfaction with nurse-patient communication and perceived health outcomes. A subset of participants will be selected for in-depth interviews to explore their experiences and perceptions of the communication with their nurses.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including rolling recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing within the hospital.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the significance of nurse-patient communication in supporting new mothers who have had an emergency c-section. Recommendations will be presented for supporting nurses and midwives in improving outcomes for new mothers who had complications during birth.

5. Social Work Research Proposals

- Experiences of negotiating employment and caring responsibilities of fathers post-divorce

- Exploring kinship care in the north region of British Columbia

Consider this hypothetical social work research proposal:

The Role of a Family-Centered Intervention in Preventing Homelessness Among At-Risk Youthin a working-class town in Northern England

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effectiveness of a family-centered intervention provided by a local council area in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth. This case study will use a mixed-methods approach with program evaluation data and semi-structured interviews to collect quantitative and qualitative data .

Introduction: Homelessness among youth remains a significant social issue. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in addressing this problem and identify factors that contribute to successful prevention strategies.

Literature Review: A review of the literature has demonstrated several key factors contributing to youth homelessness including lack of parental support, lack of social support, and low levels of family involvement. It also demonstrates the important role of family-centered interventions in addressing this issue. Drawing on current evidence, this study explores the effectiveness of one such intervention in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth in a working-class town in Northern England.

Research Design and Methods: The study will evaluate a new family-centered intervention program targeting at-risk youth and their families. Quantitative data on program outcomes, including housing stability and family functioning, will be collected through program records and evaluation reports. Semi-structured interviews with program staff, participants, and relevant stakeholders will provide qualitative insights into the factors contributing to program success or failure.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Budget: Expenses include access to program evaluation data, interview materials, data analysis software, and any related travel costs for in-person interviews.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in preventing youth homelessness, potentially informing the expansion of or necessary changes to social work practices in Northern England.

Research Proposal Template

Get your Detailed Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

This is a template for a 2500-word research proposal. You may find it difficult to squeeze everything into this wordcount, but it’s a common wordcount for Honors and MA-level dissertations.

Your research proposal is where you really get going with your study. I’d strongly recommend working closely with your teacher in developing a research proposal that’s consistent with the requirements and culture of your institution, as in my experience it varies considerably. The above template is from my own courses that walk students through research proposals in a British School of Education.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

8 thoughts on “17 Research Proposal Examples”

Very excellent research proposals

very helpful

Very helpful

Dear Sir, I need some help to write an educational research proposal. Thank you.

Hi Levi, use the site search bar to ask a question and I’ll likely have a guide already written for your specific question. Thanks for reading!

very good research proposal

Thank you so much sir! ❤️

Very helpful 👌

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES